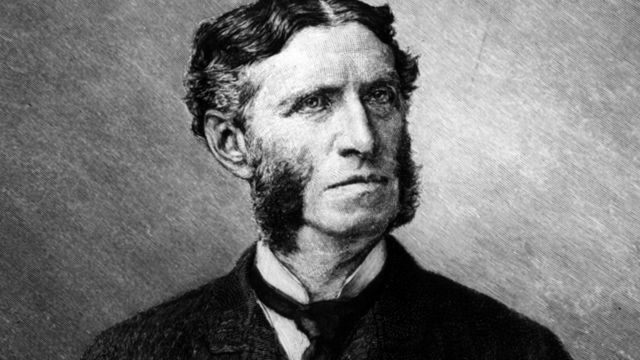

I use today’s essay to sort further sort through my feelings about Matthew Arnold. In last week’s essay about Shelley I talked about two strains, one benign and the other reactionary, that I see arising out of Arnold’s thinking. The benign version is the one we’re all familiar with: literature humanizes us by opening our minds to the humanity of others, thereby helping foster a tolerant society. The reactionary we saw gain ascendency in the National Endowment for the Humanities during the Reagan and H. W. Bush administrations: literature can be used to enshrine middle class privilege and discourage various out groups from ascending to power.

In the benign version, literature—along with the other liberal arts disciplines—encourages the open-mindedness that is necessary if a multicultural and multi-class society is to function. There is certainly this dimension in Arnold’s thinking.

Arnold is concerned that the aristocracy, the middle class, and the working class are having trouble getting along because each is selfishly concerned about its own special needs. If each could only focus on something higher than itself—that something higher being what is best in ourselves—then we could live in harmony and avoid anarchy. Culture expresses the human goal of perfectibility and should (in Arnold’s mind) be the foundation of the State. In Culture and Anarchy (1869) he writes,

People of the aristocratic class want to affirm their ordinary selves, their likings and dislikings; people of the middle-class the same, people of the working-class the same. By our everyday selves, however, we are separate, personal, at war; we are only safe from one another’s tyranny when no one has any power; and this safety, in its turn, cannot save us from anarchy. And when, therefore, anarchy presents itself as a danger to us, we know not where to turn.

But by our best self we are united, impersonal, at harmony. We are in no peril from giving authority to this, because it is the truest friend we all of us can have; and when anarchy is a danger to us, to this authority we may turn with sure trust.

Arnold believes that if culture is the basis of the State, then the aristocracy will act responsibly, giving up its ancient but now out-of-date privileges. The populace, meanwhile, will refrain from “rowdy” behavior. In other words, all classes together will follow the path of truth and light to create a more equitable and accepting society.

It must be noted, however, that Arnold’s vision is motivated in part by fear. He wants the middle class, of which he is a member, to command the authority that the aristocracy did of old but is worried that they won’t be able to pull it off. If they fail, the working class won’t respect them or stay in their place. In Democratic Education Arnold has a dire warning for his class, which he accuses of philistinism:

With their narrow, harsh, unintelligent, and unattractive spirit and culture, [the middle classes] will almost certainly fail to mould or assimilate the masses below them, whose sympathies are at the present moment actually wider and more liberal than theirs. They arrive, these masses, eager to enter into possession of the world, to gain a more vivid sense of their own life and activity. In this their irrepressible development, their natural educators and initiators are those immediately above them, the middle classes. If these classes cannot win their sympathy or give them their direction, society is in danger of falling into anarchy.

The middle class has two options. On the one hand, embrace culture themselves and impress this culture on the lower classes, in which case there will be social harmony. On the other, use force to keep the lower classes down. Arnold prefers the first but he is not above advocating for the second if necessary. Note how, in the following passage from Culture and Anarchy, he attacks liberals for their tolerance:

I remember my father, in one of his unpublished letters written more than forty years ago, when the political and social state of the country was gloomy and troubled, and there were riots in many places, goes on, after strongly insisting on the badness and foolishness of the government, and on the harm and dangerousness of our feudal and aristocratical constitution of society, and ends thus: “As for rioting, the old Roman way of dealing with that is always the right one; flog the rank and file, and fling the ringleaders from the Tarpeian Rock!” And this opinion we can never forsake, however our Liberal friends may think a little rioting, and what they call popular demonstrations, useful sometimes to their own interests and to the interests of the valuable practical operations they have in hand, and however they may preach the right of an Englishman to be left to do as far as possible what he likes, and the duty of his government to indulge him and connive as much as possible and abstain from all harshness of repression. …. [T]hat monster processions in the streets and forcible irruptions into the parks…ought to be unflinchingly forbidden and repressed; and that far more is lost than is gained by permitting them. Because a State in which law is authoritative and sovereign, a firm and settled course of public order, is requisite if man is to bring to maturity anything precious and lasting now, or to found anything precious and lasting for the future.

So Culture (of which literature is a major part) is supposed to help us all get along and Culture is supposed to help the middle class maintain superiority over the lower class.

When put this way, one better understands the attacks against feminism and multiculturalism by NEH directors William Bennett and Lynne Cheney in the 1980s and early 1990s. The “dead white men” of western lit were declared superior to all other authors, and attempts to introduce women and minority writers into the pantheon were derided as political correctness. Seen politically, it was a reaction to the demands by African Americans, women, and other minorities for more say in governing. “Jane Austen, not Alice Walker”—as one slogan had it—was a way of delegitimizing the newcomers, reminding them that they didn’t belong.

My own work has been largely in reaction to the culture wars of the 1980s and early 1990s, and I have been vociferous in advocating for Austen AND Alice Walker (although I would replace the latter with Toni Morrison, whom I consider more on a par with Austen). I guess that makes me a benign Arnoldian, believing as I do that literature can help foster conversations that will lead to an egalitarian and just society. But perhaps I should call myself a Shelleyite rather than an Arnoldian as I believe that significant social transformation is necessary if the potential of all is to be realized. Unlike Arnold, I’m not content with keeping class relations as they currently are.

One Trackback

[…] describes the Leavisites, they sound very much in the tradition of Matthew Arnold, the subject of a post last […]