Thursday

My Theories of the Reader class yesterday discussed how Picture of Dorian Gray was used to prosecute Oscar Wilde. Surprisingly, we found ourselves agreeing more with opposing attorney Edward Carson than with Wilde about the novel’s influence. Contra Wilde, we concluded that the novel had in fact impacted readers. We just thought that its influence was a good thing.

I couldn’t have chosen a better case study to conclude the semester. In the course of our discussion we cited Plato, Sir Philip Sidney, Percy Shelley, Matthew Arnold, and Hans Robert Jauss.

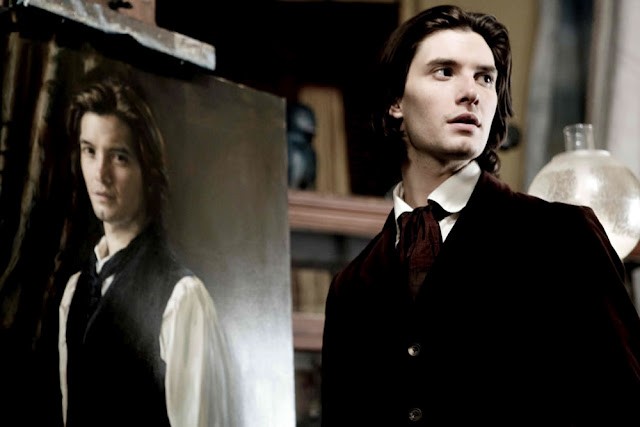

The father of Oscar Wilde’s lover had all but forced the trial by calling out Wilde as a sodomite. Although technically the plaintiff, Wilde was essentially the defendant as Carson set out to prove that he was indeed a corrupting homosexual. If he was, then the Marquess of Queensberry had not falsely libeled him. Dorian Gray entered into the fray, in part because (so Carson contended) it endorses homosexuality, in part because the defense was attempting to cast Wilde as Sir Henry Wotton, who corrupts Dorian.

The endorsement was seen in artist Basil Hallward’s admiration for Dorian, which Carson read aloud to the court:

I turned half-way round and saw Dorian Gray for the first time. When our eyes met, I felt that I was growing pale. A curious sensation of terror came over me. I knew that I had come face to face with some one whose mere personality was so fascinating that, if I allowed it to do so, it would absorb my whole nature, my whole soul, my very art itself. I did not want any external influence in my life. You know yourself, Harry, how independent I am by nature. I have always been my own master; had at least always been so, till I met Dorian Gray. Then—but I don’t know how to explain it to you. Something seemed to tell me that I was on the verge of a terrible crisis in my life. I had a strange feeling that fate had in store for me exquisite joys and exquisite sorrows. I grew afraid and turned to quit the room. It was not conscience that made me do so: it was a sort of cowardice. I take no credit to myself for trying to escape.

Later in the cross-examination, Carson read another Basil declaration:

[F]rom the moment I met you, your personality had the most extraordinary influence over me. I was dominated, soul, brain, and power, by you. You became to me the visible incarnation of that unseen ideal whose memory haunts us artists like an exquisite dream. I worshipped you. I grew jealous of every one to whom you spoke. I wanted to have you all to myself. I was only happy when I was with you. When you were away from me, you were still present in my art…But, as I worked at [the portrait], every flake and film of colour seemed top me to reveal my secret, I grew afraid that the world would know of my idolatry. I felt, Dorian, that I had told too much.

Carson asked Wilde, “Do you mean to say that that passage describes the natural feeling of one man towards another?” If he had answered “no,” Wilde would have had to disavow the beauty of Basil’s passion. Instead he answered, “I think it is the most perfect description of what an artist would feel on meeting a beautiful personality that was in some way necessary to his art and life.”

In other words, homosexual love—if that is what Basil feels—can be beautiful. Imagine now that you are Lord Alfred Douglas encountering Dorian Gray as a 19-year-old Oxford student. One can understand why he read it over and over. Brought up to believe that the same sex desires he secretly harbored were sordid and shameful, he could now see them as something to cherish. At 21, he sought out Wilde and they became lovers.

In other words, the novel gave him artistic permission to embrace his sexual orientation. From Plato’s point of view, this is why guardians must censor the reading of young people, who can otherwise be led astray (although Plato certainly wouldn’t have had objections to this particular issue). From Matthew Arnold’s point of view, this was art failing to perform art’s function of keeping the barbarians from storming the gates. Or as an 1890 review in The Daily Chronicle put it,

Man is half angel and half ape, and Mr. Wilde’s book has no real use if it be not to inculcate the “moral” that when you feel yourself becoming too angelic you cannot do better than to rush out and make a beast of yourself. There is not a single good and holy impulse of human nature, scarcely a fine feeling or instance that civilization, art, and religion have developed throughout the ages as part of the barriers between Humanity and Animalism that is not held up to ridicule and contempt in Dorian Gray.

From Percy Shelley’s point of view, on the other hand, this is art speaking on behalf of human liberation, which Shelley sees as the essence of art. In Jauss’s framework, this is art challenging the prevailing horizon of expectations. People rejected it because it called for them to see reality differently.

In the trial, Wilde argued that he was just creating beauty, not putting forward views. (“Views belong to people who are not artists.”) Essentially, Wilde was taking a page out Sir Philip Sidney here, that “the Poet, he nothing affirms.” Or as Wilde put it in his preface to Dorian Gray, which Carson quoted, “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written.”

Another version of the idea also appears in the preface: “No artist has ethical sympathies. An ethical sympathy in an artist is an unpardonable mannerism of style.”

And what if Dorian Gray were read as forwarding “a certain tendency,” as Carson contended? Wilde replied that he wasn’t responsible for what readers take away from his books. “I am concerned only with my view of art. I don’t care twopence what other people think of it.”

And yet he could not have been displeased that LBGTQ readers have been turning to Dorian Gray from Lord Douglas on. Carson certainly knew that they did, which is why he found the novel to be dangerous. He was wrong about homosexuality being bad, but he was right that Dorian Gray was social dynamite.