Friday

I’m exhausted this week, what with classes beginning and, even more draining, the death of my best friend. I’m therefore taking the easy way out for today’s post and just sharing a section from my book project on Literature and Life: How Books Change Our Lives (for Better and for Worse). This section is on reception theorist Hans Robert Jauss, whose work assured me in graduate school that I wasn’t crazy to think that literature changed lives, even though none of those around me considered this a valid question. When I taught Jauss in my Theories of the Reader class last fall, he proved to be the most popular theorist we studied.

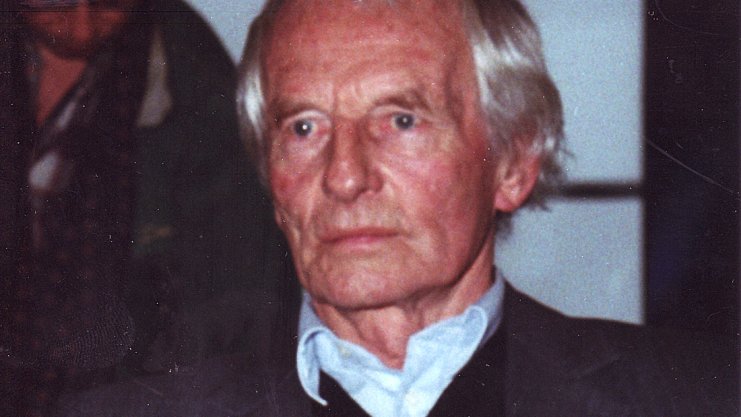

The Academy is empirical, which means that scholars who believe in literature’s impact would like proof. Is there some way of measuring if literature changes behavior and, if so, by how much? In the 1970s Hans Robert Jauss of the University of Constanz came up with a model for assessing literature’s ability to change history.

Jauss argues that a work never appears in a vacuum but is always in dialogue with its readers’ “horizon of expectations.” To gauge a work’s impact, one should look at how the horizon changes.

The horizon that mainly interests Jauss is the public’s expectation with regard to form. An author knows generally what readers are expecting when they approach a work and so can either give them what they want or give them something new. Lesser works—Jauss calls such works “culinary”—will merely satisfy what people expect and will not stretch their vision of what the genre could accomplish. It’s as though one goes into a fast food restaurant and gets exactly what one expects. Great works, by contrast, open up a new set of possibilities.

Jauss sees a work’s distance from expectations as a sign of its quality:

The distance between the horizon of expectations and the work, between the familiarity of previous aesthetic experiences and the “horizon change” demanded by the response to new works, determines the artistic nature of a literary work along the lines of the aesthetics of reception: the smaller this distance, which means that no demands are made upon the receiving consciousness to make a change on the horizon of unknown experience, the closer the work comes to the realm of “culinary” or light reading. This last phrase can be characterized from the point of view of the aesthetics of reception in this way: it demands no horizon change but actually fulfills expectations, which are prescribed by a predominant taste, by satisfying the demand for the reproduction of familiar beauty, confirming familiar sentiments, encouraging dreams, making unusual experiences palatable as “sensations” or even raising moral problems, but only to be able to “solve” them in an edifying manner when the solution is already obvious…

For an example, Jauss contrasts the reception of two novels that appeared in 1857, the all-but-forgotten Fanny by Feydeau and Madame Bovary. The first was a huge success, going through 13 editions, whereas the second was brought up on trial for obscenity. Yet for all that, the two works have similar themes:

They treated a trivial subject—adultery—the one in a bourgeois and the other in a provincial milieu. Both authors understood how to give a sensational twist to the conventional, rigid triangle which in the erotic scenes surpassed the customary details. They presented the worn-out theme of jealousy in a new light by reversing the expected relationship of the three classic roles. Feydeau has the youthful lover of the “femme de trente ans” [30-year-old woman] becoming jealous of his lover’s husband, although he has already reached the goal of his desires, and perishing over this tormenting situation.

Accounting for their very different receptions, Jauss says, is differences in form. Fanny had “the personable tone of a confessional novel” whereas Flaubert pioneered a new style called “impersonal telling” or “free indirect style” (style indirect libre). Even though Fanny depicts immoral actions in a titillating way, the readers are aware of the prevailing social values (and are aware that the author knows them) whereas those values don’t appear present in Madame Bovary. Instead, readers must figure out the moral foundation on their own. In Flaubert’s censorship trial, the prosecution took exception with the following passage:

But when she saw herself in the glass she wondered at her face. Never had her eyes been so large, so black, of so profound a depth. Something subtle about her being transfigured her. She repeated, “I have a lover! a lover!” delighting at the idea as if a second puberty had come to her. So at last she was to know those joys of love, that fever of happiness of which she had despaired! She was entering upon marvels where all would be passion, ecstasy, delirium.

Jauss observes,

The prosecuting attorney regarded the last sentences as an objective description which included the judgement of the narrator and was upset over this “glorification of adultery,” which he considered to be even more dangerous and immoral than the misstep itself. In this Flaubert’s accuser fell victim to an error as the defense immediately pointed out. The incriminating sentences are not an objective determination of a person characterized by her feelings that are formed from novels. The scientific device consists in revealing the inner thoughts of this person without the signals of direct statement…The effect is that the reader must decide for himself whether he should accept this sentence as a true statement or as an opinion characteristic of this person.

Jauss’s point is that, before Flaubert helped innovate this new form of storytelling, the horizon of expectations instructed readers to find moral signals within the text. They expected the work to signal what they should approve and what disapprove. When the signals disappeared, readers were outraged—or were until they learned to make a horizon change.

Jauss appears at first to limit his discussion to formal innovations, but his idea that horizons of expectations determine how we see reality opens the door for more ambitious discussions of how literature can impact lives. His formulation brings to mind Thomas Kuhn’s landmark work Structure of Scientific Revolutions in which Kuhn introduces the idea of paradigm shifts. People see reality a certain way, Kuhn said—say, that the sun revolves around the earth—until great minds come along (Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo) and get us to see reality in a new way, which then becomes the new norm. Brecht, as we have seen, saw art playing such a role (he even wrote a play about Galileo), disturbing what had until that point just been seen as “the way things are” or “common sense.” Not surprisingly, Jauss acknowledges a debt to Brecht.

One can see Flaubert involved in such a paradigm shift in the example that Jauss gives. In making moral judgment the responsibility of the reader rather than some higher authority, impersonal telling is pushing against authoritarian tendencies and towards democratic ones. Indeed, it was this aspect of Madame Bovary that drew that loudest complaints from the prosecution:

The consternating effect of the formal innovation in Flaubert’s narrative style was obvious in the trial: the impersonal narrative form forces his readers not only to perceive things differently—“photographically exact” according to the judgement of the time—but it also forced them into an alienating insecurity about their judgment. Since the new stylistic device broke with an old novelistic convention—unequivocal description and well-founded moral judgment about the characters—Madame Bovary could radicalize or raise questions of life, which during the trial caused the original motive for the accusation, alleged lasciviousness, to recede into the background.

Before Flaubert (although to be fair, Jane Austen uses impersonal telling in Emma), readers relied on authors to provide a formal set of rules, either through omniscient narration or through other textual hints. With these guides gone, readers felt as though there were wandering in an amoral world. The prosecution’s summation of the case against Flaubert makes this clear:

Who can condemn the woman in the book? No one. Such is the conclusion. There isn’t in the novel one person who can condemn her. If you can find one virtuous person, if you can find one moral principle that stigmatizes adultery as a sin, then I’ll admit that I have been wrong.

Jauss sympathizes with the prosecution’s unease:

If no character presented in the novel could condemn Emma Bovary and if no moral principle is asserted in whose name she could be condemned, is not general “Public opinion” and its basis in “religious feeling” questioned along with the principle of “marital fidelity”? To what authority should the case of Madame Bovary be presented if the previously valid standards of society, “public opinion, religious beliefs, public morals, good manners,” are no longer sufficient for judging this case? These open and implicit questions do not by any means indicate an aesthetic lack of understanding or moral philistinism on the part of the prosecuting attorney. Rather, there is expressed in them the unsuspected influence of a new art form which can by means of a new way of seeing things jolt the reader of Madame Bovary out of the belief that his moral judgment is self-evident and reopen the long-closed question of public morals.

The court agreed with the prosecution and, while it acquitted Flaubert, it condemned “the literary school which they supposed him to represent.” Jauss observes that this school was, in reality, “his stylistic device, as yet not recognized.”

The Flaubert example is a tidy example of an audience’s changing response signaling the impact of a work, but the question is whether Jauss’s model can handle other kinds of responses. For instance, can it handle a work that is only recognized as a masterpiece centuries after it was written (for instance, King Lear and Shakespeare’s sonnets)? How about authors whose reputations go up and down (Rudyard Kipling, who was up, then down, and is now back up)? Or works that, when they appear, are appreciated by some and hated by others (Jane Eyre)?

Jauss addresses the first in ways similar to how Shelley does. Shelley, you will recall, talked about great literature that has a vision that isn’t understood for centuries. Jauss too says it can take that long before the horizon catches up with the work, allowing us to appreciate it:

The distance between the actual first perception of work and its virtual significance, or, put another way, the resistance that the new work poses to the expectations of its first audience, can be so great that it requires a long process of reception to gather in that which was unexpected and unusable within the first horizon. It can thereby happen that a virtual significance of the work remains long unrecognized until the “literary evolution,” through the actualization of a newer form, reaches the horizon that now for the first time allows one to find access to the understanding of the misunderstood older form…One can line up the examples of how a new literary form can reopen access to forgotten literature. These include the so-called “renaissances”—so-called, because the word’s meaning gives rise to the appearance of an automatic return, and often prevents one from recognizing that literary tradition cannot transmit itself alone. That is, a literary past can return only when a new reception draws it back into the present, whether an altered aesthetic attitude willfully reaches back to reappropriate the past, or an unexpected light falls back on forgotten literature from the new moment of literary evolution, allowing something to be found that one previously could not have sought in it.

To repeat the example I used with Shelley, Shakespeare’s cross-dressing comedies, most notably Twelfth Night and As You Like It, present the idea that gender is far more fluid than previous societies, including his own, were willing to acknowledge. In his depictions of women with a male side and women with a female side, of women who desire other women and men who desire other men, he was capturing what we now openly acknowledge to be human realities, even though neither his own society nor many societies thereafter were as tolerant. It took us centuries before we could find within those plays what “one previously could not have sought in it.”

Jauss’s theory shares affinity with avant garde art of the 1920s, whose goal was to shock the bourgeoisie (thinking of Duchamp labeling a urinal “Fountain”). For the Dadaists, the mark of a work’s effectiveness lay in its shock effect. The assumption here is that artistic truth will be unpleasant. Jauss’s framework is often the most fruitful, then, when looking at works like Madame Bovary that created controversy. In my own classes, I encourage my students to use a Jaussian framework when they examine works that have been banned or caused a furor, like, say, Huckleberry Finn, Catcher in the Rye, Lolita and the like.

But a work need not necessarily shock to be horizon changing. Or it may shock some people but not others, as Alice in Wonderland did. Rigid moralists objected to Lewis Carroll’s work, but people who felt constrained by a suffocating morality and an educational system found that it allowed them to vent in an amusing way, and they felt superior to that stuffy moralists who condemned it.

The case of Jane Eyre is particularly interesting in this light. It attracted one of the most brutal reviews in the history of English letters—an attack by one Elizabeth Rigby—but it also was a bestseller. Looking back, one can see that Rigby understood the novel better than many of its fans, who chose to turn a blind eye to its radical call for female autonomy and focus instead on the romance. The fact that the novel would go on to speak to unionizing governesses, suffragettes, and 1970s feminists makes the case that Rigby was on to something. Only recently, with the 20XX BBC television series, are we seeing a rendition of the novel that focuses more on Jane’s self-assertion than—as with movies throughout the 20th century—the marriage plot. In other words, maybe it took 150 years for our horizon to catch up with the novel.

It may be that Jauss’s horizon of expectations theory, as originally conceived, was too rigid. There is not a fixed stair step set of expectations or a single horizon that holds true for an entire society but a variety of horizons that can fluctuate. This leads to horizon changes that are less spectacular than a whole society undergoing a reality change but probably closer to how belief systems actually evolve. To gauge a work’s impact on readers using Jauss’s framework, then, requires that we identity the particular set of expectations that a work is engaging and then look for evidence about whether as to whether those expectations have shifted.