Friday

In my Theories of the Reader course, I have been teaching how Matthew Arnold believed the middle class could use literature to consolidate their power while keeping the working class in their place, what we now call soft power or hegemony. As Terry Eagleton memorably sums up the view, “If the masses are not thrown a few novels, they may react by throwing up a few barricades.”

New York Review of Books just reviewed a new book describing how Hitler and Mussolini also sought to weaponize the arts. Benjamin Martin’s The Nazi-Fascist New Order for European Culture looks at their use of cinema, literature, music, art and sculpture to bend the rest of Europe to their will. Reviewer Roger Paxton sums up Martin’s project as follows:

[C]ultural concerns were in fact vital to the imperial projects of Hitler and Mussolini. We do not normally associate their violent and aggressive regimes with “soft power.” But the two dictators were would-be intellectuals—Adolf Hitler a failed painter inebriated with the music of Wagner, and Mussolini a onetime schoolteacher and novelist. Unlike American philistines, they thought literature and the arts were important, and wanted to weaponize them as adjuncts to military conquest. Martin’s book adds a significant dimension to our understanding of how the Nazi and Fascist empires were constructed.

The German project can be traced back to World War I propaganda and it lasted well into World War II:

During World War I German patriotic propaganda vaunted the superiority of Germany’s supposedly rooted, organic, spiritual Kultur over the allegedly effete, shallow, cosmopolitan, materialist, Jewish-influenced “civilization” of Western Europe. Martin’s book shows how vigorously the Nazis applied this traditional construct. Hitler invested considerable money and time in the 1930s, and even after World War II began, in an effort to take over Europe’s cultural organizations and turn them into instruments of German power. These projects had some initial success. In the end, however, they collapsed along with the military power they were designed to reinforce.

Italy, according to Martin, was less successful than Germany as it tried to convince Hitler that it was Greece to Germany’s Rome. The Italian effort foundered upon German contempt.

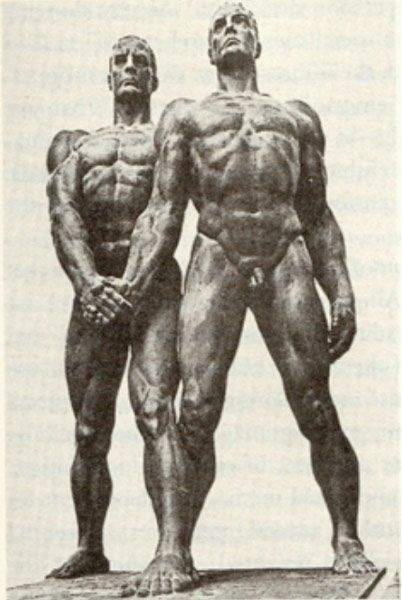

Hitler advocated aggressive governmental intervention into cultural matters. Art was to be the expression of “the hereditary racial bloodstock,” and the artist’s job was to defend the German Volk. When PEN International objected to Hitler expelling “leftists” and Jews from the German chapter, Hitler closed down the chapter altogether.

Paxton’s review talks more about cinema and music than literature, but it does mention the European Writers’ Union, founded in 1941, which attracted one Nobel prize laureate and a bunch of minor writers. They were drawn in part by the Nazis’ rejection of modernism:

As with music, the Nazis were able to attract writers outside the immediate orbit of the Nazi and Fascist parties by endorsing conservative literary styles against modernism, by mitigating copyright and royalty problems, and by offering sybaritic visits to Germany and public attention. Some significant figures joined, such as the Norwegian novelist Knut Hamsun, winner of the 1920 Nobel Prize in literature, but most were minor writers who employed themes of nationalism, folk traditions, or the resonance of landscape.

In the end, however, the fascists’ arts project was doomed to fail as art cannot operate within such narrow constraints:

A major obstacle to the success of Axis “inter-national” cultural organizations—especially with the Nazis—was their ideological narrowness. While an alignment with militant antimodernism attracted conservative writers and artists, these generated little excitement compared to the modernists. Hitler’s efforts to stem the mass appeal of Hollywood films and jazz only made them (as Martin suggests) more seductive and, in a final irony, prepared for the triumph of American music, jeans, and film in the postwar world by trying to make them taboo.

In my class, we have been discussing theorists who argue that literature can work as a form of social indoctrination. Bertolt Brecht and Antonio Gramsci see this occurring with class, Frantz Fanon and Chinua Achebe with colonialism, W.E.B. Du Bois with race, and various feminists and queer theorists with gender. While they have some reason to worry, the fascist failure shows that literature also has a way of slipping its leash whenever those in authority try to control it. Governments may turn to art because it is cheaper than a heavy police presence, but they soon learn that they can never control artists as much as they want to.

In other words, warnings about the arts brainwashing us may exaggerate the danger.

Previous posts on Nazis and literature

Freikorps Fantasies and Trump’s Policies