Tuesday

Yesterday I discussed how some feminists have argued that even great novels like Pride and Prejudice, Emma, and Jane Eyre support patriarchal marriage. Austen and Bronte, however, at least have the excuse that they were writing in the 19th century. What are we to make of the “chick lit” romances written today?

Tania Modleski, in Loving with a Vengeance: Mass Produced Fantasies for Women, examines the charge that novels like Bridget Jones’s Diary do active harm. Modleski’s book, which originally appeared in 1982, broke new ground when she took Harlequins, gothic romances, and soap operas seriously. While she didn’t exactly see them as progressive, she defended them as helping women cope with the prospect of male violence. Even though the heroines always end with Mr. Right, the books acknowledge the pain of female powerlessness before they get to that point. In other words, they do more than propose a good man as the answer to all your problems.

In her introduction to the second edition (2008), Modleski attacks those who think that great literature will counteract the reactionary seductions of chick lit. Since I myself think that great literature is more effective than such romances in handling our problems, I examine Modleski’s arguments closely here.

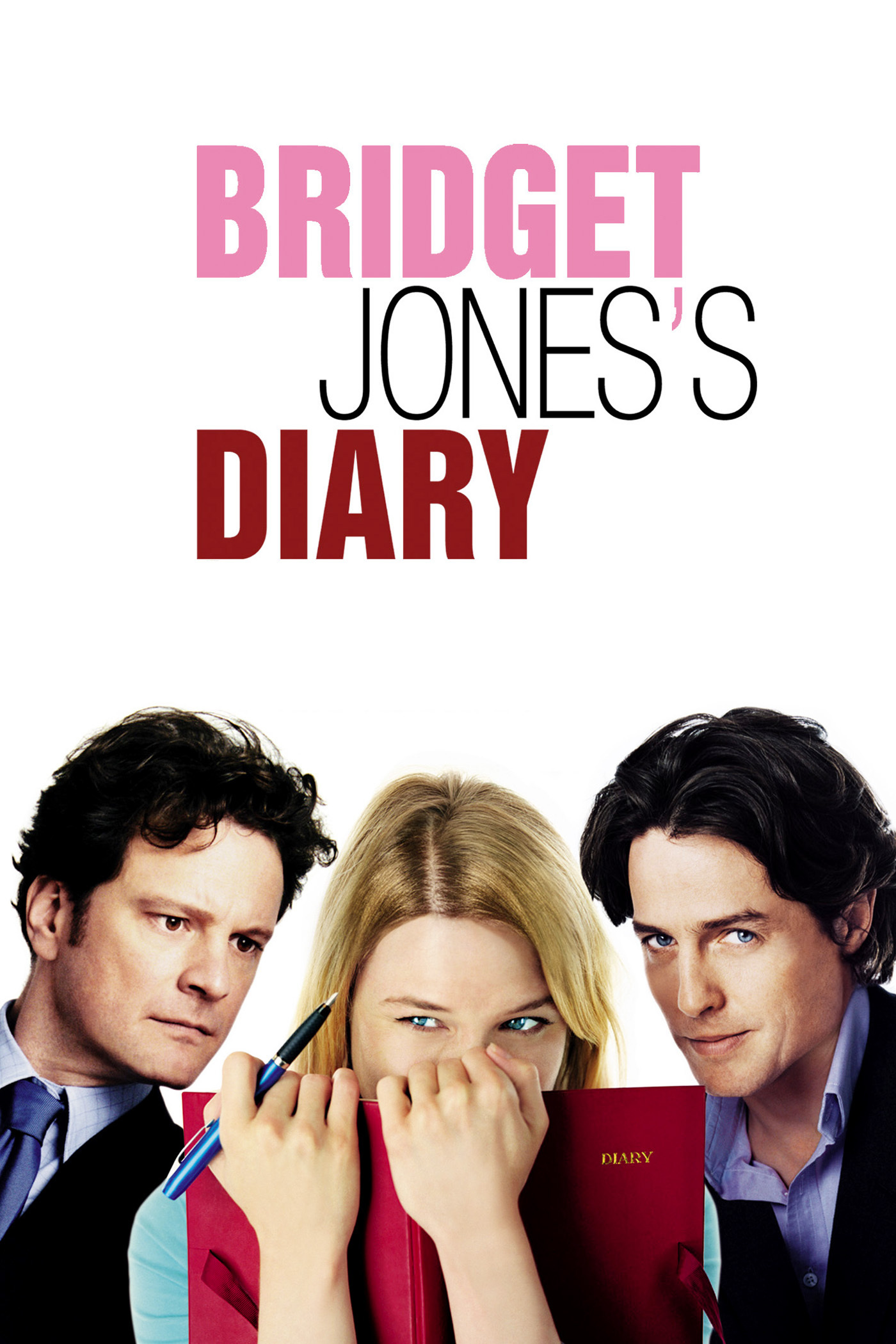

First, a description of Bridget Jones gives us a sense of what chick lit involves. Modleski points out that the novel is modeled loosely on Pride and Prejudice:

The author, Helen Fielding, created a ditzy character who is hilariously skeptical of marriage but hoping against hope to evade the fate of “singletons”—dying alone at the end of their lives and, not being immediately missed by anyone, are finally discovered half eated by their Alsatian dog. Bridget is obsessed with controlling her weight and limiting her alcohol and tobacco intake, and throughout much of the novel she is embroiled in an unhealthy relationship with her boss, an attractive cad.

In 2001, many were horrified by the world-wide popularity of Bridget Jones and of chick lit in general. Modleski sarcastically writes,

Will it come as a surprise to anyone that the condemners of the “damned mobs of scribbling women” (to use Nathaniel Hawthorne’s notorious label) are bemoaning the success of chick lit, which seems to have taken by storm not only England and America but many other countries as well? In fact the worldwide popularity of chick lit has led one writer to refer to the phenomenon as a “pandemic”—the avian flu, if you will, of the literary world—that is felling those portions of the female population not fortunate enough to have been immunized by adequate doses of the Great Books.

One critic was Dorris Lessing, who wrote,

It would be better, perhaps, if [young chick lit authors] wrote books about their lives as they really saw them, and not these helpless girls, drunken, worrying about their weight and so on.

Modleski doesn’t tangle with Lessing but she does heap scorn on Elizabeth Merrick, who complains,

Chick lit’s formula numbs our senses. Literature by contrast, grants us access to countless new cultures, places, and inner lives. Where chick lit reduces the complexity of the human experience, literature increases our awareness of other perspectives and paths. Literature employs carefully crafted language to expand our reality, instead of beating us over the head with clichés that promote a narrow worldview. Chick lit shuts down our consciousness. Literature expands our imaginations.

Modleski accuses Merrick of “mind-numbing humanist platitudes,” but that’s not really an argument. Philosopher Martha Nussbaum makes a more sophisticated version of Merrick’s argument. Modleski, while taking high culture elitists to tasks, herself engages in a complicated dance about whether she should judge negatively the popular literature that she studies.

She identifies two ways of studying mass-produced fantasies, the ethnographic approach and the psychoanalytic approach. The first seeks to suspend judgement altogether, putting feminist politics aside and treating Harlequin fans or soap fans the way one would treat any culture.

The psychoanalytic approach, by contrast, sees women as oppressed and believes that they turn to literary fantasies as an unconscious way to resist and fight back, or at least to cope, with patriarchy. Is Modleski, when she sees Harlequin reader trapped by patriarchy, any the less elitist than Baratz-Logsted, who says they would be better served by great literature. Note how slippery Modleski gets, beginning her self-defense by seeming to agree before she disagrees:

One cannot quarrel with the notion that feminist critics ought not to engage in attacking or presuming to direct other women. But are there no limits to the actual support a feminist critic ought to extend to their struggles and their terms. To take an example, if romance writers and readers were to defend their genre or other forms of popular culture on the grounds of man’s natural superiority to women, should feminist critics simly go along with these “terms?” Do we not have an obligation as feminists to contest such notions? How can criticism call itself feminist if it is not first and foremost an engaged criticism.

Modleski, in other words, wants to have it both ways. She wants to take seriously women who read mass produced fantasies (which is good, everyone should be taken seriously) and she thinks that women should not be pinning all their hopes on romantic fantasies. In other words, she thinks she knows better than they do what’s good for them. When she calls other people elitist, she may be doing so to deflect such charges against herself.

I’m all for seeing mass produced fantasies as more complex that they’ve been given credit for. Modleski’s book is very useful in that regard. But I also see “Great Books” as even more complex and as far better for readers.