Monday

The Las Vegas shootings demonstrate once again a grim reality that Donald Trump, with his Muslim ban, refuses to acknowledge: Americans are more likely to be killed by “white American men with no connection to Islam than by Muslim terrorists or foreigners” (Vox). Projecting our fears onto monstrous foreigners when the real threat is closer to hand is a fact that Beowulf, my go-to poem for mass killings, understands very well.

Tom Friedman’s New York Times column last week vividly captures the disconnect:

If only Stephen Paddock had been a Muslim … If only he had shouted “Allahu akbar” before he opened fire on all those concertgoers in Las Vegas … If only he had been a member of ISIS … If only we had a picture of him posing with a Quran in one hand and his semiautomatic rifle in another …

If all of that had happened, no one would be telling us not to dishonor the victims and “politicize” Paddock’s mass murder by talking about preventive remedies.

No, no, no. Then we know what we’d be doing. We’d be scheduling immediate hearings in Congress about the worst domestic terrorism event since 9/11. Then Donald Trump would be tweeting every hour “I told you so,” as he does minutes after every terror attack in Europe, precisely to immediately politicize them.

Vox, meanwhile, provides specifics and statistics:

Here are just a few of the attacks that have occurred in 2017:

- Sunday night, a 64-year-old white man from Nevada opened fire on a crowd of more than 22,000 people at a country music festival in Las Vegas, killing more than 50 and wounding more than 200.

- In August, a 20-year-old white Nazi sympathizer from Ohio sped his car into a crowd of anti-racist protesters in Charlottesville, Virginia, killing a woman and injuring at least 19 others.

- In June, a 66-year-old white man from Illinois shot at Republican Congress members during an early morning baseball practice, severely wounding several people including Rep. Steve Scalise of Louisiana, the House of Representatives Majority Whip.

- In March 2017, a 28-year-old white man from Baltimore traveled to New York City with the explicit aim of killing black men. He stabbed 66-year-old Timothy Caughman to death and was charged with terrorism by New York state authorities.

- In May, a 35-year-old white man from Oregon named Jeremy Joseph Christian began harassing Muslim teenagers on a train in Portland, telling them “We need Americans here!” Two men interceded; Christian then stabbed and killed them both.

In fact, between 2001 and 2015, more Americans were killed by homegrown right-wing extremists than by Islamist terrorists, according to a study by New America, a nonpartisan think tank in Washington, DC.

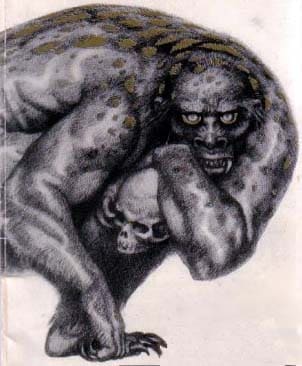

When I teach Beowulf, I always tell my students to look for the familiar form that the monsters take. We may think the poem is about trolls and dragons, but it is really about warriors and kings.

In today’s post I go through almost every name mentioned in Beowulf and show how he or she is related to the poem’s focus on destructive anger. Although the poem may seem to digress, one can see its thematic unity once one surveys all of the characters.

The destructive anger that Beowulf explores has three different aspects, each of which threatens to plunge society into chaos. I’ve divided the characters associated with each anger into those that are part of the problem and those that attempt to solve it. Of course, Beowulf usually models the best solution although occasionally he is part of the problem as well.

Grendel – Murderous resentment

Grendel’s resentful rage is the rage that we see in many of our mass killers. See the links at the end of last week’s post on Las Vegas for the many times I’ve compared these killers to Grendel.

Part of the problem

— Unferth is the warrior who first challenges Beowulf. Reported to have killed kinsmen, he fears that Beowulf will take away his privileged position at the feet of the king and insults him. To his credit, he later makes peace with Beowulf, giving him his sword.

–Hrothgar’s nephew Hrothulf is designated as regent to Hrothgar’s sons but, dissatisfied with that role, kills one and attempts to kill the other after Hrothgar dies. The infighting, which will tear apart the heretofore stable Danish kingdom, is symbolized by the destruction of the great hall of Heorot.

–Cain is Grendel’s ancestor. His anger over God preferring Abel’s gift, leading him to murder, makes him the archetype of resentful rage.

–Modthryth, the shrewish princess who visits death on any man who gazes at her, is the one character that doesn’t fit neatly into my framework. Perhaps she is a form of female resentment, taking out her frustrations against men as the contrasting figure of Queen Hygd (see below) does not. Modthryth cleans up her act after she marries the brave Offa.

Attempts at a solution

–Wealththeow, Hrothgar’s queen, who lobbies for Hrothulf when she fears that Hrothgar will disinherit their sons in favor of Beowulf, will pay for her decision when Hrothful, as regent, goes after those sons. Diplomacy is good but you can’t close your eyes to the real nature of the people you’re dealing with.

–Hygd, queen of the Geats, disperses treasure generously, thereby assuring that warriors will not become resentful.

–Hygelac, king of the Geats, is like his wife in his generosity and so deserves a place here. But he also shows up in the next section as one who participates in, and is killed by, a continuing blood feud.

–Time and again Beowulf refuses to become a resentful warrior. He gives the wealth won for killing Grendel to Hygelac (who, as a good king should, redistributes it back), and he turns down an offer of the throne when Hygelac dies (from Hygd), vowing instead to support next-in-the-line-of-succession Heardred. The poem reassures us (if you are reassured by something that someone does not do) that Beowulf “never cut down a comrade who was drunk.”

Grendel’s Mother – Grief that lashes out (hot rage)

We have but to see how the United States responded to 9-11 with two wars, one still hot, to understand the destabilizing power of grief that is determined to make someone pay. In Beowulf’s time, hot grieving led to interminable blood feuds.

Part of the problem

–Beowulf’s father Ecgtheow involves the Danes in a possible blood feud by fleeing to Hrothgar after killing a man.

–Hengest fights to a draw in a battle with Finn but loses his brother Hnaef. Despite their truce, the thoughts of revenge that he stores up all winter prove too powerful and he rises up to slay Finn the following spring.

–Aeschere, Hrothgar’s best friend who is killed by Grendel’s mother, is the victim of the blood feud started by Beowulf killing Grendel.

–Geat King Hrethel starts a blood feud with the Swedes. His son Hygelac will kill the Swedish king Ongentheow. In turn, the Swedes, led by Onela will eventually kill Hygelac and then his son Heardred, leaving the throne to Beowulf—who will then send aid to one Eadgils, a friendless Swede, who overthrows and kills Onela.

Attempts at a solution

–Women are sometimes used to patch up quarrels, such as Hildeburh, who is married to Frisian Finn to bring peace between him and the Danes. It doesn’t work and she loses both her son (a Frisian) and her brother Hnaef (a Dane) in the subsequent fighting.

—Freawaru is another of these doomed peace offerings, intended to patch up a quarrel between the Danes and the Heatho-Bards. Beowulf predicts that her marriage to Heatho-Bard king Ingeld will not solve the problem. (“A passionate hate will build up in Ingeld, and love for his bride will falter in him as the feud rankles.”)

–Onela is briefly mentioned as one who forgives Weohstan, an ancestor of Wiglaf, for killing his nephew Eanmund. Healthy though this forgiveness seems, it loses some of his luster once we learn that Onela wanted Eanmund dead.

–Beowulf is such a strong king that he is able to deter the Swedes and the Franks from continuing blood feuds against the Geats. Think of it as peace through strength. The solution is temporary, however: after Beowulf dies, his kinsman Wiglaf predicts that they will be overrun by one of these kingdoms, probably the Swedes, who haven’t forgotten Beowulf’s role in killing Swedish king Onela.

The Dragon – Grief that shuts down, depression (frozen rage)

Dragon depression is the coin side of Grendel’s Mother’s rage, the depression into which people retreat when they are grieving, whether over a friend or the disappointments of life. Like dragons, they hunker down and scale over. Poison runs in their veins.

Frozen rage turns into hot fire when they are prodded, and they can emerge from their caves and burn down everything around them. To reach out to such people means risking their flames.

Part of the problem

–Danish king Hrothgar is at risk of sinking into depression after Grendel’s mother kills Aeschere. Beowulf, a young foreign warrior, has to tell him, “Bear up and be the man I expect you to be.”

—Heremod is a legendarily bad king who becomes bitter and avaricious as he grows old, so that he is a burden to his people. He may be the king that Hrothgar has in mind when he describes how “an element of overweening enters him and takes hold while the soul’s guard, its sentry, drowses.”

—The Last Veteran loses all of his friends and finally retreats into a funeral barrow with all his riches. That barrow is his heart, which is where the dragon will makes its home.

–Geat king Hrethel, in addition to his role in the blood feud with the Swedes that claims the lives of two sons and a grandson, retreats to his bed and dies of grief after a third son is accidentally killed by one of the others.

—Beowulf is part of the problem. While he doesn’t hoard riches, as other kings do, one can see that he hoards fame, thereby disempowering his men. The dragon burns down his house, a sign that he has been consumed by dragon depression, and we see him summing up his life as one meaningless death after another. He also has been irresponsible in failing to insure a competent successor for the Geats. In this way, he is guilty of dragon-like self absorption.

Attempts at a solution

–Kings who put the good of their nation over their own personal disappointments, who don’t let the bitterness that can come with aging distract them, all fall into this category. These include the four kings responsible for Danish greatness: Shield Sheafson, Beow, Halfdane, and Hrothgar. As noted above, however, Hrothgar initially falls into depressed inactivity following the death of Aeschere.

—Sigemund, a legendary king and “fence round his fighters,” is contrasted with Heremod, an archetype of a bad king (see above). Sigemund is described as a dragon slayer.

—Offa, who marries Modthryth, is another exemplary king and gives birth to exemplary offspring, including Eomer.

—Beowulf is also part of the solution. One can think of him as fighting the dragon within and, more significantly, of opening himself to the help of another—Wiglaf—in that battle. As a result, the king triumphs over the dragon.

To return to Thomas Friedman’s point, if Las Vegas shooter Stephen Paddock had been a Muslim, many Americans would have seen him as a monstrous troll. Because he was a white man, however, he instead is an Unferth or a Hrothulf, someone we see around the work place.

“We have met the enemy,” Walt Kelly famously wrote, “and he is us.” Heroes listen to the needs of society, not to their own fears.