Friday

I’m currently on a Wilkie Collins kick, having just started on The Moonstone after finishing The Woman in White. In Moonstone there is a wonderful instance of a character whose use of literature could serve as a parody of my blog. House steward Gabriel Betteridge believes in Better Living through Robinson Crusoe.

Betteridge has been called to give his account of the events leading up to the disappearance of the fabled moonstone. Daunted by the task, he turns to Defoe’s novel, his guide in all things. The book falls open to the following passage:

Now I saw, though too late, the Folly of beginning a Work before we count the Cost, and before we judge rightly of our own Strength to go through with it.”

Betteridge finds consolation that someone else has experienced what he is going through:

Two hours have passed since Mr. Franklin left me. As soon as his back was turned, I went to my writing-desk to start the story. There I have sat helpless (in spite of my abilities) ever since; seeing what Robinson Crusoe saw, as quoted above—namely, the folly of beginning a work before we count the cost, and before we judge rightly of our own strength to go through with it. Please to remember, I opened the book by accident, at that bit, only the day before I rashly undertook the business now in hand; and, allow me to ask—if that isn’t prophecy, what is?

Betteridge then explains the importance of the book for him:

I am not superstitious; I have read a heap of books in my time; I am a scholar in my own way. Though turned seventy, I possess an active memory, and legs to correspond. You are not to take it, if you please, as the saying of an ignorant man, when I express my opinion that such a book as Robinson Crusoe never was written, and never will be written again. I have tried that book for years—generally in combination with a pipe of tobacco—and I have found it my friend in need in all the necessities of this mortal life. When my spirits are bad—Robinson Crusoe. When I want advice—Robinson Crusoe. In past times when my wife plagued me; in present times when I have had a drop too much—Robinson Crusoe. I have worn out six stout Robinson Crusoes with hard work in my service. On my lady’s last birthday she gave me a seventh. I took a drop too much on the strength of it; and Robinson Crusoe put me right again. Price four shillings and sixpence, bound in blue, with a picture into the bargain.

Later in his account, Betteridge recalls how Robinson Crusoe came to his aid when he was eased out of his position as bailiff into the less arduous one of house steward:

The perturbation in my mind, in regard to thinking about it, being truly dreadful after my lady had gone away, I applied the remedy which I have never yet found to fail me in cases of doubt and emergency. I smoked a pipe and took a turn at Robinson Crusoe. Before I had occupied myself with that extraordinary book five minutes, I came on a comforting bit (page one hundred and fifty-eight), as follows: “Today we love, what tomorrow we hate.” I saw my way clear directly. Today I was all for continuing to be farm-bailiff; tomorrow, on the authority of Robinson Crusoe, I should be all the other way. Take myself tomorrow while in tomorrow’s humour, and the thing was done. My mind being relieved in this manner, I went to sleep that night in the character of Lady Verinder’s farm-bailiff, and I woke up the next morning in the character of Lady Verinder’s house-steward. All quite comfortable, and all through Robinson Crusoe!

At another point, he turns to Crusoe when asked to venture out into the rain to track down the mysterious foreigners who have been seen around the house:

It was all very well for him [the master] to joke. But I was not an eminent traveller—and my way in this world had not led me into playing ducks and drakes with my own life, among thieves and murderers in the outlandish places of the earth. I went into my own little room, and sat down in my chair in a perspiration, and wondered helplessly what was to be done next. In this anxious frame of mind, other men might have ended by working themselves up into a fever; I ended in a different way. I lit my pipe, and took a turn at Robinson Crusoe.

Before I had been at it five minutes, I came to this amazing bit—page one hundred and sixty-one—as follows:

“Fear of Danger is ten thousand times more terrifying than Danger itself, when apparent to the Eyes; and we find the Burthen of Anxiety greater, by much, than the Evil which we are anxious about.”

The man who doesn’t believe in Robinson Crusoe, after that, is a man with a screw loose in his understanding, or a man lost in the mist of his own self-conceit! Argument is thrown away upon him; and pity is better reserved for some person with a livelier faith.

I second Betteridge but expand his contention: those who don’t believe in literature generally have a screw loose in their understanding. Argument is thrown away upon them.

Further thought: I just realized that Betteridge uses Robinson Crusoe as Crusoe himself uses the Bible. Perhaps that is where he (or Wilkie Collins himself) got the idea. In a practice known as bibliomancy, Crusoe lets the good book fall open at moments of crisis. Here’s an example following his panic after witnessing the cannibals on his island:

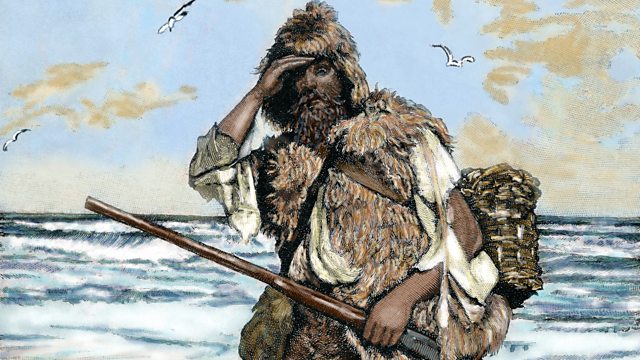

[W]hen I had done praying I took up my Bible, and opening it to read, the first words that presented to me were, “Wait on the Lord, and be of good cheer, and He shall strengthen thy heart; wait, I say, on the Lord.” It is impossible to express the comfort this gave me. In answer, I thankfully laid down the book, and was no more sad, at least on that occasion.