Tuesday

I come not to praise Harold Bloom, who died yesterday, but to bury him. Although he is much lauded, I have always found him frustratingly opaque. Someone once wrote that he wasn’t wise, just “well-read,” and in my irritation I latched onto that put-down.

To be sure, I had to acknowledge that his knowledge of literature was immense—he memorized Paradise Lost as a child, he claimed to be able to read a thousand pages an hour, and he produced a veritable library full of critical collections. When he picked up a poem, he could identify the influences immediately. But I always felt that, for him, poetry was chiefly about previous poetry.

He is best known for The Anxiety of Influence, where he imagined poets engaged in Oedipal battles with those who came before. Either you were successful, becoming a great poet in your own right, or you failed and were merely (shudder!) derivative. The anxiety of not being original sometimes led great poets (as Bloom saw it) to misrepresent their precursors, misreading them and then attacking them for what they supposedly said. Only when these poets found their own voices could they magnanimously go back and find something good to say about their predecessors.

While there are some poets who fit this model (for instance, T.S. Eliot appears to have been anxious about Tennyson), there are many who don’t. Furthermore, it may be more of a male thing. Susan Gubar and Sandra Gilbert in The Madwoman in the Attic argue that women authors see their predecessors more as supportive sisters than as rivals, and I suspect the same is true of many male poets.

The theory probably says more about Bloom than about poets in general. Check out Bloom’s view of reading as a power struggle in a passage that my poet friend Norman Finkelstein alerted me to:

Disabuse yourself of the lazy notion that any activity is disinterested, and you arrive at the truth of reading. We want to be kind, we think, and we say that to be alone with a book is to confront neither ourselves nor another. We lie. When you read, you confront either yourself, or another, and in either confrontation you seek power. Power over yourself, or another, but power. And what is power? Potentia, the pathos of more life, or to speak reductively, the language of possession.

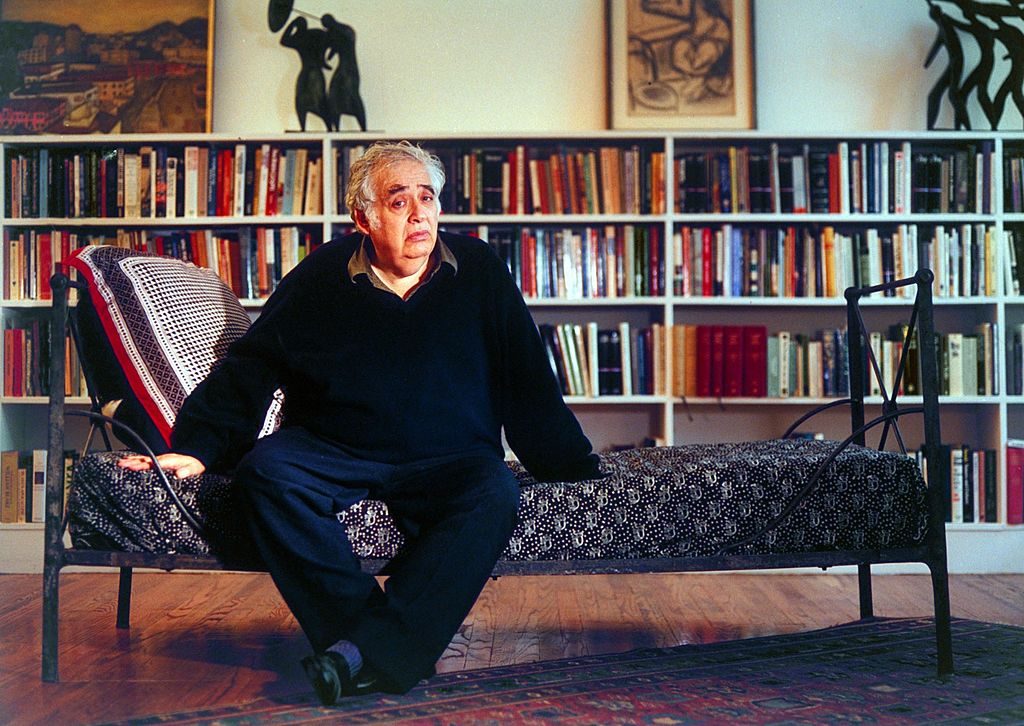

While Norman reluctantly finds a disagreeable truth in the assertion, I don’t recognize myself in the description. I certainly see it at work in Bloom, however. The critic and scholar he most emulated—and who he therefore never ceased to criticize even while praising him—was the 18th century’s Samuel Johnson, a man who resembled him in girth as well as in extraordinary reading abilities. The latter half of the 18th century is sometimes referred to as “the Age of Johnson.”

But while Johnson often said brilliant things about poets like Shakespeare, Dryden, and Pope, he didn’t confine himself to poetry. He also said brilliant things about all manner of subjects, including the vanity of human wishes, the human search for happiness, and procrastination. Whenever I read Johnson, I’m always struck by how he knows me better than I know myself.

Bloom, on the other hand, seldom opens up the world in ways I find useful or enlightening. He is no Samuel Johnson, and we haven’t been living in the Age of Bloom.

Bloom had some bestsellers during the culture wars of the 1990s, but I always wondered if people didn’t buy his books more because of what Bloom represented than what he wrote. He set himself as a grand judge of all literature, championing the classics and accusing the elevation of certain women and writers of color as literary affirmative action. Some of his pronouncements strike me as nuts, like elevating Thomas Pynchon over Toni Morrison.

While I’m all in on revering the classics, at times Bloom struck me as encouraging a sort of literary idolatry, instructing us to genuflect before genius without seriously engaging with it. Or at least engage with it in a way that made sense to me.

I might have taken him more seriously had I better understood his project, and I’m open to seeing him differently. From my current perspective, however, I see him as having made more of an impact through his anthologies and collections than through his ideas. As a Samuel Johnson wannabe, he struck me as (shudder!) derivative.