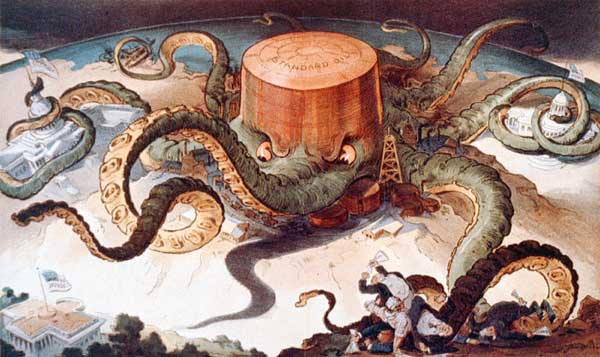

Standard Oil as octopus in an early 20th century cartoon

Standard Oil as octopus in an early 20th century cartoon

Today I want to talk about metaphor and its use in political discourse. Metaphor, or more broadly figurative language, is at the core of what makes literature literature. Figurative language packs a punch because it is doesn’t confine itself to the literal level. It connotes as well as denotes, as we lit critics used to say.

Skillful politicians, both the principled and the unscrupulous, know how to use metaphor to their advantage. In the process, they can make links between a variety of different issues that otherwise seem unconnected. The 1960’s New Critics used to call these links “image clusters” and could show how they thematically hold a work of art together, even one that seems to meander in different directions.

Let’s look at a not-so-nice image cluster. Certain Tea Party activists associate a president who doesn’t look like them with the Spanish-speaking immigrants who are pouring into their communities, who they blame for unemployment and stagnant salaries. One of these people the president elevated to the Supreme Court. Because Obama doesn’t look like us, he wants to take away our Medicare and give minorities preferential treatment and use the power of the federal government to do whatever he wants with us, including taking away our guns. Because he’s Muslim and not really American, he has contempt for things American and wants to hasten America’s decline. Any Republican who is willing to work with this socialist fascist tyrant must be drummed out of the party.

French social critic Roland Barthes calls such chains-of-association “mythologies” and notes that they are far more powerful than reason. (Note the Tea Partiers’ contempt for both science and intellectuals.) In Barthes’s view, the right is better at myth-making than the left:

Statistically, myth is on the right. There, it is essential; well-fed, sleek, expansive, garrulous, it invents itself ceaselessly. It takes hold of everything, all aspects of law, of morality, of aesthetics, of diplomacy, of household equipment, of Literature, of entertainment.

While I basically agree this is how myth-making works, I’m skeptical that it is limited to the right. Mao seemed as effective a myth-maker as Hitler. Maybe Barthes thinks the left is more rational because he’s a leftist.

In fact, I’m worried that we might start seeing the rise of left-wing tea partiers. I can imagine that the horrors of the Gulf of Mexico oil spill could spawn leftist mythologies (call them creatures of the black lagoon). Just think about it: this grimy and suffocating substance that sullies all things pure is the perfect symbol for dirty companies that put profits before people (just as Massey Coalmining did). The spewing oil wells are like the spewing right-wing media pundits, a fitting metaphor for their lies and invective. The oil is also like the torrent of corporate money that is about to come flooding into the political process thanks to a rightwing activist Supreme Court. The oil spill is sullying the environment the way that Wall Street hedge fund managers befouled the entire economy. And then there’s the war in Iraq, which was fought because of oil. And now we’re mired down in two wars (another oil image). And on and on.

The problem with such spiraling imagery is that, like poetry, it goes straight to the bloodstream, whereas we want our leaders making decisions with their heads as well as their hearts and guts. These decisions include trade-offs, such as, say, the ones Obama was essaying when he called for limited off-shore oil drilling as part of a comprehensive energy plan.

As a recent New York Times editorial noted, we could cease all off-shore oil drilling in the United States, but that would just have the effect of exporting more of our oil spills overseas. (Nigeria apparently has had 200 oil spills over the past 20 years, a number of them the equivalent of the Exxon Valdez). I mention this example, not because I’m in favor of off-shore oil drilling (I’m ambivalent), but to point out that running a country and solving our problems can’t occur when various mythologies are dominating our thinking, whether from the right or from the left. Right-wing mythologies are dominating Republican thinking at the moment, and if these myths continue to gum up the wheels of governing (another oil metaphor), then the left may feel it is to their advantage to join in. At the present, they are resisting the urge. But for how much longer?

And if they do, then even our rational, pragmatic, problem-solving, compromise-seeking, slightly-to-the-left-of-center president might find himself swamped.

So watch out for metaphors. They’re great in poetry and in inspirational leadership. But as Mario Cuomo once pointed out, while we may campaign in poetry, we must govern in prose. Right now there are too many people who think we can spend all our time in (not very good) poetry.

5 Trackbacks

[…] The Dangerous Power of Metaphor […]

[…] The Dangerous Power of Metaphor […]

[…] The Dangerous Power of Metaphor […]

[…] The Dangerous Power of Metaphor […]

[…] [My thanks to Meghan O’Meara of Speaking Globally: Thoughts on Global Issues in Context for steering me to this article. O’Meara is looking for metaphors that are being used to describe the oil disaster and links to one of my own posts on “The Dangerous Power of Metaphor.”] […]