Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at [email protected]. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Friday

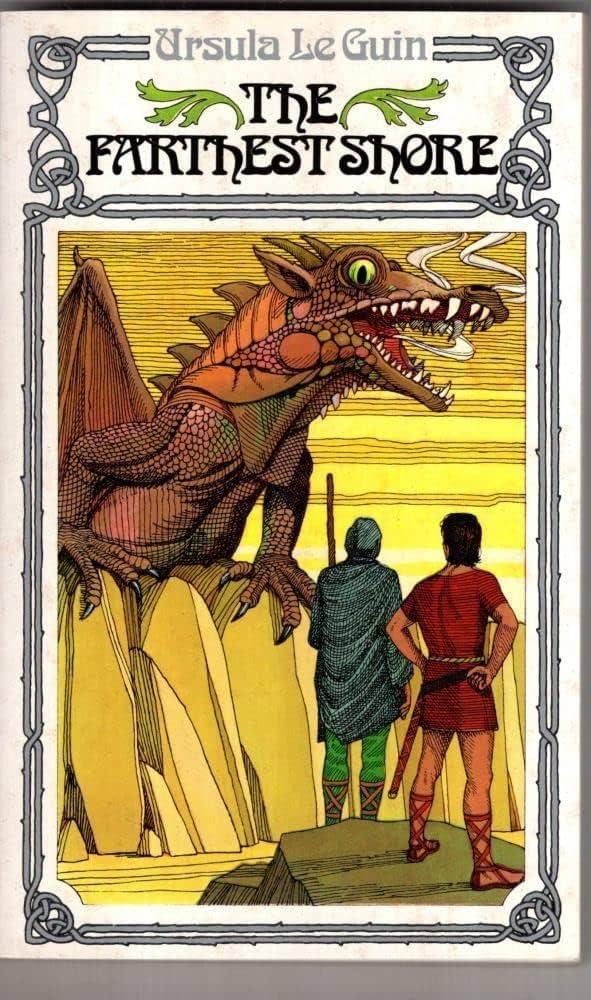

As I think about the Democrats’ transition from Joe Biden to Kamala Harris, a literary torch-passing novel comes to mind. In Ursula Le Guin’s The Farthest Shore, the third work in her Earthsea series, the young prince Arren finds roles reversed when he must carry his beloved mentor, the archmage Ged, to safety. The novel provides us insights applicable to this year’s election.

By discovering the secret of eternal life, the dark wizard Cob has become the world’s most powerful force, but in doing so he unleashes a blight that robs humanity of magic, song, and story. In response, the revered archmage has enlisted the aid of an untested youth, and together they travel to a shadowy realm between life and death that exists at the end of the world. Ged triumphs over Cob but, in the process, he uses up all his magic, forcing Arren into a leadership role.

Cob has amassed his power by giving the world what it thinks it wants: which is perpetual stasis and no death. But such an existence pulls us out of the cycle of life, with its highs and lows, its beginnings and endings. To deny our participation in nature’s rhythms is to opt for an existence bereft of color and light. Ged and Arren restore the balance by defeating Cob, and in the end Arren proves to be the king of the Western Isles that the fractured world has needed. Ged serves as the bridge to this new order.

Think of Donald Trump and J.D. Vance as the dark wizard Cob in that they are promising their followers a return to 1950s America. This is an America run by straight, white, Christian men in which everyone else (people of color, Jews, Muslims, women, LGBTQ+ folk, workers) accept their subordinate status. Like the shadowy world presided over by Cob, this America lacks the rich diversity that in fact makes up our present reality. Their vision is as monochromatic as the one described by Le Guin, who is talking of a dragon ally that Cob has just killed:

His death did not diminish life. Nor did it diminish him. He is there—there, not here! Here is nothing, dust and shadows. There, he is the earth and sunlight, the leaves of trees, the eagle’s flight. He is alive. And all who ever died, live; they are reborn and have no end, nor will there ever be an end. All, save you. For you would not have death. You lost death, you lost life, in order to save yourself.

As a bi-racial woman (half Afro-Caribbean, half south Asian) who early embraced same-sex marriage and has her own interracial marriage with a Jewish man and two stepchildren, Kamala Harris taps into the American promise that all should have equal access to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Arren has his own vision of a rejuvenated society in Farthest Shore:

How long has it been, seventeen years or eighteen, since the Ring of the King’s Rune was returned to the Tower of the Kings in Havnor? Things were better for a while then, but now they’re worse than ever. It’s time there was a king again on the throne of Earthsea, to wield the Sign of Peace. People are tired of wars and raids and merchants who overprice and princes who overtax and all the confusion of unruly powers.

The book’s drama lies in how one gets from stasis to renewal. Dark wizard Cob can be seen as Ged’s shadow, the side of us that wants to keep things as they are rather than embrace the uncertain world of change. I myself was rooting for Biden (I trusted those political scientists that predicted he would win) because I feared an uncertain succession. But while most of us like the safety of the familiar, Trump and Vance—with their call to return America to its racist and sexist past—embrace a particularly noxious variant of this desire.

In the final showdown, Ged tells Cob that, in embracing a vision that elevates power over love and darkness over light, he has robbed the world of its richness. Le Guin borrows imagery from T.S. Eliot’s “Hollow Men,” to convey the dead that Cob is keeping alive:

Behind [the man] stood others, all with sad, staring faces. They seemed to speak, but Arren could not hear their words, only a kind of whispering blown away by the west wind.

And later:

[H]e saw the mother and child who had died together, and they were in the dark land together; but the child did not run, nor did it cry, and the mother did not hold it or ever look at it. And those who had died for love passed each other in the streets.

There are no loud Kamala laughs in this world, no boisterous celebrations.

Early in the novel on the gated island of Roke, some of the great wizards in residence refuse to acknowledge the danger. An emergency council meeting is held in which some argue for staying put. One wizard opines that “to raise a great fear on so little a foundation is unneedful. Our power is not threatened only because a few sorcerers have forgotten their spells.” A second wizard agrees:

Have we not all our powers? Do not the trees of the Grove grow and put forth leaves? Do not the storms of heaven obey our word? Who can fear for the art of wizardry, which is the oldest of the arts of man?

Like Biden, however, Ged realizes that staying the course is not an option and sets out on a quest, surprising everyone with his selection of the young prince as companion. In the end, Arren proves his worth, carrying Ged out of the land of the dead after the wizard has exhausted his powers:

“Thy way, lad,” Ged said in a hoarse whisper. “Help me.”

So they set out up the slopes of dust and scoria into the mountains, Arren helping his companion along as well as he could. It was black dark in the combes and gorges, so that he had to feel the way ahead, and it was hard for him to give Ged support at the same time. Walking was hard, a stumbling matter; but when they had to climb and clamber as the slopes grew steeper, that was harder still. The rocks were rough, burning their hands like molten iron.

Endurance carries them through the ordeal and then a dragon flies them back to the capital city of Havnor, just as an eagle saves Frodo and Sam after they have accomplished their mission. Upon arriving, Arren learns that he is the change the world has been waiting for:

Then [Ged] turned to Arren, who stood tall and slight, in worn clothes, and not wholly steady on his legs from the weariness of the long ride and the bewilderment of all that had passed.

In the sight of them all, Ged knelt to him, down on both knees, and bowed his grey head.

Then he stood up and kissed the young man on the cheek, saying, “When you come to your throne in Havnor, my lord and dear companion, rule long and well.”

Ged here is like Biden, putting the welfare of the world before his own egotistical desires. As the president said in his Wednesday night address, “I revere this office, but I love my country more.”

Returning to our own story, Joe Biden, in 2020, saved the country from an authoritarian grifter with a Christian nationalist following that was threatening to upend the American Constitution and to usher in a vision of America where only straight white Christians have rights. Then, having saved America, Biden engineered a situation in which the antithesis of Donald Trump, a biracial woman who embraces LGBTQ+ and worker protections, would have a chance at succeeding him. We can safely anticipate that on January 6, 2025—like Ged relinquishing his position and returning to the island where he grew up—the president will turn over the keys to his successor and return to his Delaware.

As the Doorkeeper of the wizards’ city puts it, “He has done with doing. He goes home.”

Hopefully our story will also end happily with Arren, not Cob, stepping into executive authority.