Monday

A successful assignment in recent years has been asking my “British Couples Comedy in the Restoration and 18th Century” class to compare an older work with a contemporary film. As one student observed, suddenly they relate to comedies of manners on a much deeper level.

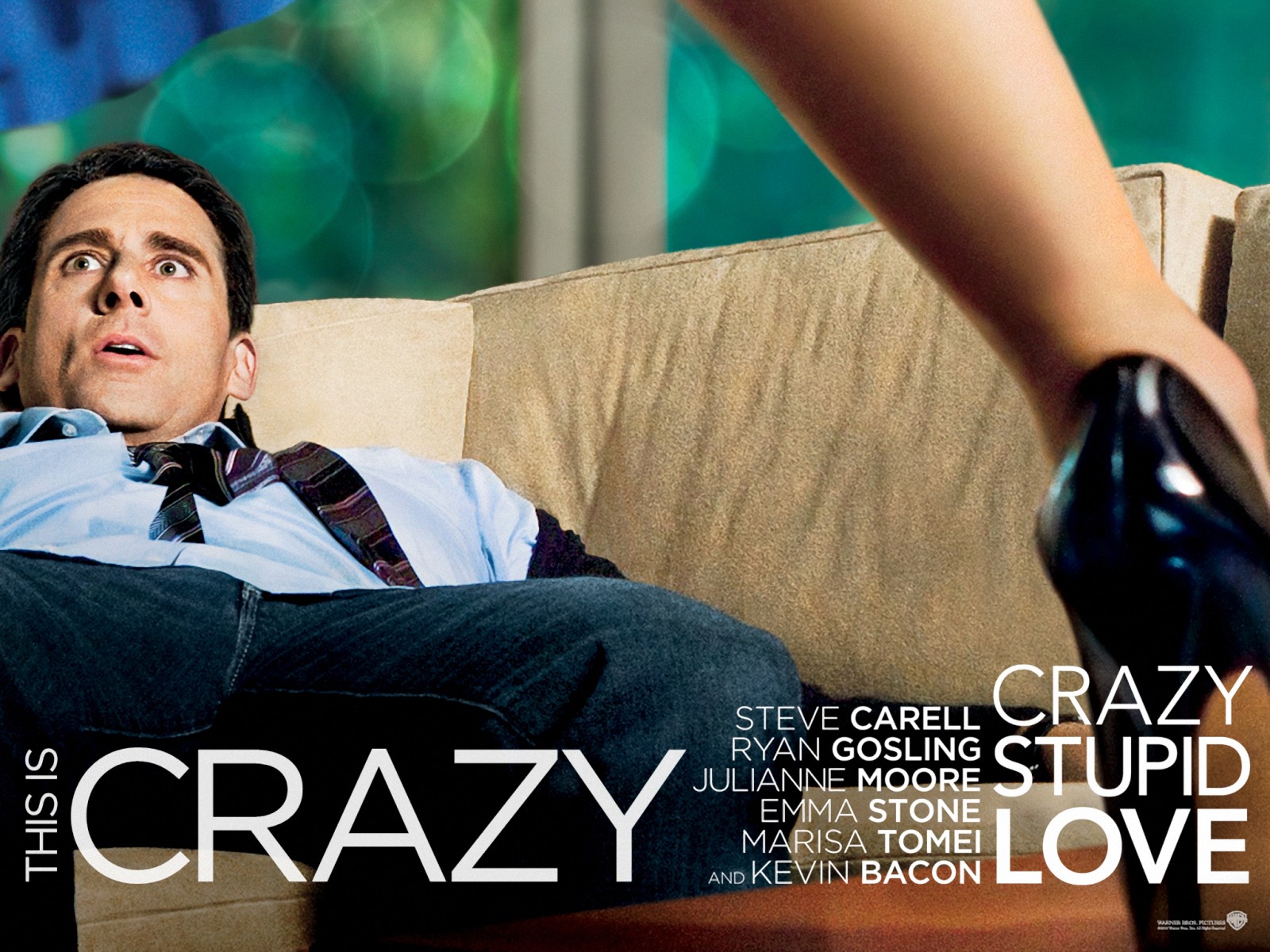

Some of the films mentioned in the essays I received recently are 10 Things I Hate about You, How To Lose a Guy in 10 Days, Friends with Benefits, Crazy, Stupid, Love, He’s Just Not That into You, Don Jon, Say Anything, Austenland, and Something Borrowed.

The comparisons bring out the enduring popularity of the genre. Relationships are always anxiety producing, and by applying Freud’s theory that laughter is a response to anxiety, we see how comedy makes the inevitable painful moments more bearable. In that respect, couples comedies are a real gift to humankind.

We decided that the humor in contemporary films is more often Shaftesburian than Hobbesian, getting us to laugh with more than laugh at (although there are exceptions). Ultimately, I think the course achieved its goals of introducing the students to wonderful older works while helping them appreciate the power of an underestimated genre. They also got to explore their own own relationship histories. There are good reasons why rom-coms are as popular now as they ever were.

Here are the essays I received:

William Wycherley’s Country Wife and Crazy, Stupid, Love

Kayla Bird found herself fascinated by male masculinity anxieties and the fear of being cuckolded, which show up in Wycherley’s play and the 2011 Steve Carell comedy. The lesson of both dramas: real men trust women, cuckolds either ignore or attempt to control them.

Aphra Behn’s The Rover and Friends with Benefits

Alaina Wall sees the philandering Wilmore in Aphra Behn’s Rover as a man afraid of emotional commitment, which of course is the situation of Jamie and Dylan in the 2011 Will Gluck film. In their case, past trauma has led them to avoid marriage. Such a past is not posited for Wilmore, however, and Helena doesn’t have the option of sex outside of marriage. Settling for second best, she entices him with the prospect of an unpredictable and exciting marriage where he is never sure of her. This doesn’t resemble traditional marriage, but it’s also more interesting than mere sexual interchange.

The Rover and Brave

In both Behn’s play and the 2012 Pixar film, the heroines do not want to be defined by marriage. Helena, whose default option is the convent, doesn’t have a choice, and Meridel’s mother tells her that she doesn’t have one either. Jenn Norris notes that we watch two heroines pushing against social expectations and finding imaginative ways of breaking free. Helena’s eventual marriage to Wilmore looks more like she’s joining his fraternity of rakes while Meridel rejects her mother’s domestication and holds on to her boyish ways.

Oliver Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer and Austenland

Liz Bailey argues that She Stoops and Austenland are direct complements. In Goldsmith’s play, Marlow feels stifled by his formal society and longs for the freer discourse he finds with an apparent barmaid. Jane, by contrast, finds nothing romantic about our freer society and longs for the more formal constraints of the Regency period. While both long for a society different than their own, they learn that love is about more than social guidelines or the lack thereof.

She Stoops to Conquer and Say Anything

Dani Bowes was interested in the parent-child relationships in Goldsmith’s play and Cameron Crowe’s 1989 film. Mr. Hardcastle and Kate provide a positive model of childrearing—they negotiate together the rules that the daughter should follow—whereas Mrs. Hardcastle spoils Toby, leading to conflict. Yet even good fathers like Hardcastle may not realize that they must eventually let go and trust their child to make the right decision, despite doubts. Their reward is that well-raised sons and daughters prove responsible.

The stifling father in Say Anything doesn’t allow Diane to make her own relationship decisions, leading to a painful rupture.

Rape of the Lock and Mean Girls

Although those writing on Pope’s mock epic were exempted from finding a film equivalent (after we kept on coming up empty), Alli Szymanski and I thought of Mean Girls once she started talking about the toxicity of beauty culture. The perfectly nice Cady Heron is seduced by “the Plastics” as the film, like the poem, sees society’s beauty obsession corrupting a young woman. Both works conclude with lectures on priorities, one from Clarissa, the other from the author of Queen Bees and Wannabes upon which the film was based:

And trust me, Dear! good Humor can prevail,

When Airs, and Flights, and Screams, and Scolding fail.

Beauties in vain their pretty Eyes may roll;

Charms strike the Sight, but Merit wins the Soul.

Richard Sheridan’s The Rivals and Don Jon

Josh Cheseman grappled with the role of fantasizing in relationships. Sheridan’s Lydia Languish refuses to enter into any relationship that doesn’t resemble a storybook romance while, in Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s 2013 film, Jon is addicted to pornography and Barbara to romance. The protagonists must learn that a real relationship is more fulfilling than a fantasy one. Lydia comes to this realization when Jack Absolute goes out to fight a duel, Jon when he meets the sympathetic Esther, who weens him off of his addiction. Barbara, unfortunately, never breaks free and winds up alone.

Hannah Cowley’s The Belle’s Stratagem and How To Lose a Guy in 10 Days

In Cowley’s play, Laetitia determines that the best way to win over her indifferent fiancé is to get him to hate her. Hate, after all, is easier to convert to love than indifference. In Donald Petrie’s 2003 film, meanwhile, Andie’s project to lose a guy by deliberately committing classic relationship mistakes ends up making her a more interesting person in Ben’s eyes (as Laetitia’s does in Doricourt’s). Eventually the two male leads realize they don’t want fantasy women but women with imagination. As Doricourt tells Letitia in the play’s conclusion,

You shall be nothing but yourself; nothing can be captivating that you are not. I will not wrong your penetration by pretending that you won my heart at the first interview, but you have now my whole soul. Your person, your face, your mind, I would not exchange for those of any other woman breathing.

Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility and He’s Not That into You

Becca Forrester makes a compelling case that Austen could have written the 2004 self-help bestseller-turned-movie about how women often misread men’s intentions. Marianne makes such mistakes, failing to register that Willoughby never actually proposes marriage but only hints at it. Elinor, on the other hand, reads the data accurately and knows that there’s something up with Edward, even though she doesn’t know what. The need to read men accurately is a basic Austen theme, especially in Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, and Emma.

Sense and Sensibility and Something Borrowed

Mairin Rivett focused on the contrast between women who ruthlessly go for what they want and those who don’t. The latter sometimes allow themselves to be exploited, which is the case in the 2011 Luke Greenfield rom-com, where the pushy Darcy steals her best friend’s man, without much pushback from the enabling Rachel. While the situation isn’t exactly that of Elinor Dashwood and Lucy Steele, applying the comparison prompts us to wonder what might have happened if Elinor had been more assertive with Edward Ferrars and less tolerant of Lucy. As it is, she only gets the man she loves by luck. By contrast, Rachel, no longer a doormat, tells Dex not to marry Darcy and he doesn’t.

Sense and Sensibility and 10 Things I Hate about You

Although Gil Junger’s 1999 film is a teen-pic adaptation of Taming of the Shrew, Sabrina Wood successfully parallels it with Austen’s novel, seeing Bianca as a Marianne and Kate as an Elinor. As such, she sees both works as cautionary relationship tales: if you leap into a relationship, you may fall for the wrong guy, but if you hold back, using your reserve as a shield, you may not get the one who is right for you. In the film as in the novel, the younger daughter eventually learns to be more prudent, the elder to step into her passions.

We think that we read and watch these works for mere entertainment. In fact, we are grappling with as big an issue as there is.

Further thought: While examining the psychological dynamics of romantic comedies, I suggested the following genre spectrum:

–rom-coms render painful relationship moments comically

–melodramas take painful relationship moments seriously

–action adventure movies address relationships through male identity dramas

–horror movies push the anxieties into the realm of nightmare, the return of the repressed

Which you like best may indicate how you prefer to handle your anxieties.