Monday

I’m late to recent reports of clown outbreaks, but as I’m currently teaching Stephen King’s It in my American Fantasy class, it gives me the opportunity to explain why many find clowns to be disturbing.

First, in case you also have been out of the clown loop, here’s what’s been going on:

The Great Clown Scare of 2016 started in the dog days of August, when a young man began wandering the streets of Green Bay, Wis., in gruesome black-and-white clown makeup, carrying black balloons. (It was later revealed that he was doing guerrilla marketing for a horror short.) A few weeks later, children in a Greenville, S.C., apartment complex told the police about clowns flashing green laser lights in nearby woods and trying to lure them with cash. The complex issued a warning to residents, but the police found nothing — not one frizzy strand of clown-wig hair.

Nevertheless, reports of sinister clowns have spread to at least 20 states, and abroad, causing school closings and several arrests. Notably, no American children have been physically harmed, though last week a man in a clown mask in Sweden stabbed a teenager in the shoulder. Law-abiding clowns are predictably upset, and have organized at least one “Clown Lives Matter” protest in response.

According to the article, there was also a noteworthy clown sighting in 1981, which may have influenced King’s 1986 story of Pennywise the clown, who rips the arms off children and does other gory things.

For my money, Sigmund Freud has the best explanation for why we are unsettled by clowns. Freud and Stephen King together help explain why we’ve had this recent clown eruption.

In his influential essay that seeks to understand the uncanny (cue the Twilight Zone theme music), Freud quotes psychologist E. Jentsch on how dolls and automatons can freak us out:

In proceeding to review those things, persons, impressions, events and situations which are able to arouse in us a feeling of the uncanny in a very forcible and definite form, the first requirement is obviously to select a suitable example to start upon. Jentsch has taken as a very good instance “doubts whether an apparently animate being is really alive; or conversely, whether a lifeless object might not be in fact animate”; and he refers in this connection to the impression made by wax-work figures, artificial dolls and automatons. He adds to this class the uncanny effect of epileptic seizures and the manifestations of insanity, because these excite in the spectator the feeling that automatic, mechanical processes are at work, concealed beneath the ordinary appearance of animation.

Freud then applies his theory of repression to the case. In figures that are both us and not us, he says, we see forbidden desires and fears that we dare not acknowledge. Because we have pushed them under and denied them, they have become toxic. They surface in the doubling of ourselves and we are horrified.

All monsters function as doubles, with Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde being perhaps the text book example. Others are Beowulf and Grendel, Frankenstein and his monster, Jane Eyre and Bertha Mason, and the list goes on.

Freud doesn’t mention clowns specifically, but his explanation applies. The classic clown has features that we recognize as our own only they are also not our own because they are exaggerated (big mouth, bulbous nose, oversized feet). Furthermore, whereas society and our parents have engrained in us the value of self-control and self-restraint, clowns are out of control. Some children like clowns because of anti-social behavior but others are disturbed because, pressured by social shaming, they have learned to control this side of themselves.

In the novel IT, Pennywise is able to change its form into the deepest fear of each of the seven child protagonists. To Eddie Kaspbrak , whose mother has infected him with her hypochondria, IT appears as a scabrous leper while Bill Denbrough, whose parents are locked in grief over the death of his brother, encounters IT in a memorial picture album.

King doesn’t confine himself to the children, however. He is out to understand the hatred of the Other that seized America in the 1980s—remember gays and AIDS, the “evil empire,” and Willie Horton?—and he sees IT behind homophobic murders, racial lynchings, and other bloodlettings. The clown always shows up, as in the following scene where he goads a town into an orgasmic massacre of a robber gang:

He wasn’t wearing a clown suit or nothing like that. He was dressed in a pair of farmer’s biballs and a cotton shirt underneath. But his face was covered with that white greasepaint they use, and he had a big red clown smile painted on. Also had these tufts of fake hair, you know. Orange. Sorta comical…[H]e was leanin out of the window so far that Biff couldn’t believe he wasn’t fallin out. It wasn’t just his head and shoulders and arms that was out; Biff said he was right out to the knees, hanging there in midair, shooting down at the cars the Bradleys had come in, with that big red grin on his face. “He was tricked out like a jackolantern that had got a bad scare,” was how Biff put it.

At the end of this post I include times I have cited IT in response to some of our recent hate crimes, including the Orlando massacre and the killing of the North Carolina Muslim couple. Fortunately, Pennywise was thwarted last week when he encouraged Kansas “crusaders” to inflict “a bloodbath” upon Muslim immigrants from Somalia.

In this election we have seen a candidate—some would call him a clown—speaking to the toxic swamp that is the American id (German for “it”). He has called for violence against protesters, obliquely suggested shooting his opponent, and conjured up images of international banking conspiracies that echo Mein Kamf. He is giving permission for people to use language and to engage in behavior—especially towards women—that we have laboriously tried to move beyond. We can applaud ourselves that we now look down on behavior that was once commonplace, but Donald Trump threatens to set us back.

If, then, we imagine an infestation of dangerous clowns invading our communities, it is not surprising. They confirm our fear that America’s dark side is close to the surface.

Update: I just saw a recent New Yorker article on clowns makes some of the connections with Donald Trump that I do. You can read it here.

Previous posts on Stephen King’s It

King Understands the Orlando Killings

King Looks for Hope in Our Children

King’s Vision of Environmental Devastation

Unlike Oklahoma, King Wants Real History

When American Fantasies Are Dangerous

Pennywise Kills North Carolina Muslims

Imagination Unleashed: Children on Bikes

How Lost Innocence Can Breed Monsters

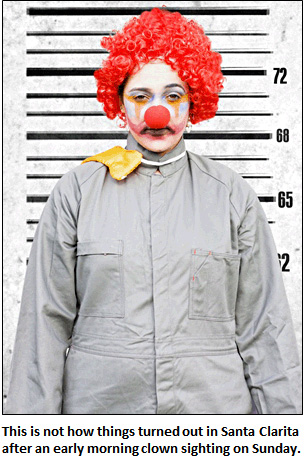

Late breaking clown news: Here’s the latest clown story, along with a picture. (The clown was found innocent.)