Sports Saturday

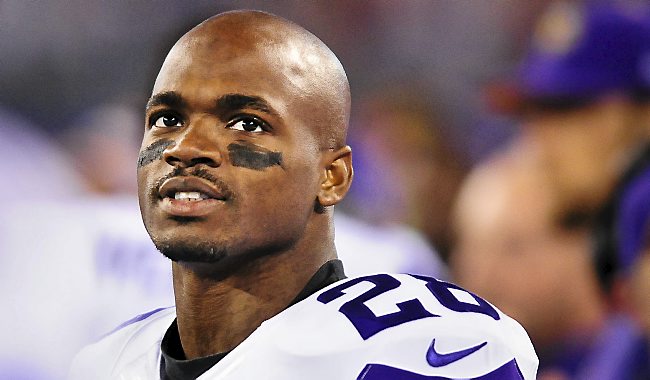

Sadly, for the second Saturday in a row I must devote my sports column to action off the playing field, this time to Vikings running back Adrian Peterson’s flogging of his four-year-old son. For flogging is what it was, even though Peterson’s defenders are calling it a spanking or a “whuppin’.”

When I hear people defending Peterson, what comes to mind are various rationalizations one encounters in British literature, from Thwackum in Tom Jones to the parents and teachers in Tom Sawyer to Baloo in The Jungle Book to Lord Peter Whimsey in Dorothy Sayers’ last short story.

Most child psychologists say that spanking accomplishes nothing positive, especially with four-year-olds. And that doesn’t even touch on a spanking that leaves cuts on the private parts that are still visible a week later. But let’s examine what different authors have to say about it.

In the Sayers story “Talboys,” a bleeding heart acquaintance of Lord Peter’s wife Harriet is appalled when he canes his son Brendon for stealing peaches. Harriet, however, defends Peter for the disciplined way he does it. He has a clear understanding with his son about the rules and the consequences for breaking them. Brendon appreciates operating under such a clear set of guidelines, and Peter does not cane him in a rage but more as an impartial referee. Harriet notes that such a regimen works only on Brendon and not on their other son, who is far more sensitive and needs a different set of consequences.

In The Jungle Book, we have Baloo arguing that his disciplinary program is necessary to keep Mowgli alive. It’s not unlike the argument that African Amerian comedian D. L. Hughley tweeted recently following Peterson’s indictment: “A fathers belt hurts a lot less then a cops bullet!” Here’s Kipling:

All this will show you how much Mowgli had to learn by heart, and he grew very tired of saying the same thing over a hundred times. But, as Baloo said to Bagheera, one day when Mowgli had been cuffed and run off in a temper, “A man’s cub is a man’s cub, and he must learn all the Law of the Jungle.”

“But think how small he is,” said the Black Panther, who would have spoiled Mowgli if he had had his own way. “How can his little head carry all thy long talk?”

“Is there anything in the jungle too little to be killed? No. That is why I teach him these things, and that is why I hit him, very softly, when he forgets.”

“Softly! What dost thou know of softness, old Iron-feet?” Bagheera grunted. “His face is all bruised today by thy—softness. Ugh.”

“Better he should be bruised from head to foot by me who love him than that he should come to harm through ignorance,” Baloo answered very earnestly. “I am now teaching him the Master Words of the Jungle that shall protect him with the birds and the Snake People, and all that hunt on four feet, except his own pack. He can now claim protection, if he will only remember the words, from all in the jungle. Is not that worth a little beating?”

Whether or not Whimsey’s and Baloo’s child-rearing practices would work in real life is not clear. At least these disciplinarians operate in a disciplined way, however. They show respect for those they spank and do not rob them of their dignity. Peterson, by contrast, appears to have lashed out in a rage.

Anyone who has had young children knows they can drive us nuts. At those moments, we have to do everything we can to remain mature adults, and sometimes we don’t entirely succeed. But when we go to the lengths that Peterson did, we cross the line into abuse.

One gets a glimpse into the anger that can build up in children who have been caned by looking at Kipling’s story “The Elephant’s Child” from his wonderful Just So Stories. There we see adults reacting badly to a child’s natural curiosity and then a child acting out a revenge fantasy.

Here’s how the story begins:

In the High and Far-Off Times the Elephant, O Best Beloved, had no trunk. He had only a blackish, bulgy nose, as big as a boot, that he could wriggle about from side to side; but he couldn’t pick up things with it. But there was one Elephant–a new Elephant–an Elephant’s Child–who was full of ‘satiable curtiosity, and that means he asked ever so many questions. And he lived in Africa, and he filled all Africa with his ‘satiable curtiosities. He asked his tall aunt, the Ostrich, why her tail-feathers grew just so, and his tall aunt the Ostrich spanked him with her hard, hard claw. He asked his tall uncle, the Giraffe, what made his skin spotty, and his tall uncle, the Giraffe, spanked him with his hard, hard hoof. And still he was full of ‘satiable curtiosity! He asked his broad aunt, the Hippopotamus, why her eyes were red, and his broad aunt, the Hippopotamus, spanked him with her broad, broad hoof; and he asked his hairy uncle, the Baboon, why melons tasted just so, and his hairy uncle, the Baboon, spanked him with his hairy, hairy paw. And still he was full of ‘satiable curtiosity! He asked questions about everything that he saw, or heard, or felt, or smelt, or touched, and all his uncles and his aunts spanked him. And still he was full of ‘satiable curtiosity!

One fine morning in the middle of the Precession of the Equinoxes this ‘satiable Elephant’s Child asked a new fine question that he had never asked before. He asked, ‘What does the Crocodile have for dinner?’ Then everybody said, ‘Hush!’ in a loud and dretful tone, and they spanked him immediately and directly, without stopping, for a long time.

And here’s the story’s conclusion, which I imagine Kipling’s child readers found very satisfying. It lets us see just how much pent up anger there can be in the victims:

One dark evening he came back to all his dear families, and he coiled up his trunk and said, ‘How do you do?’ They were very glad to see him, and immediately said, ‘Come here and be spanked for your ‘satiable curtiosity.’

‘Pooh,’ said the Elephant’s Child. ‘I don’t think you peoples know anything about spanking; but I do, and I’ll show you.’ Then he uncurled his trunk and knocked two of his dear brothers head over heels.

‘O Bananas!’ said they, ‘where did you learn that trick, and what have you done to your nose?’

‘I got a new one from the Crocodile on the banks of the great grey-green, greasy Limpopo River,’ said the Elephant’s Child. ‘I asked him what he had for dinner, and he gave me this to keep.’

‘It looks very ugly,’ said his hairy uncle, the Baboon.

‘It does,’ said the Elephant’s Child. ‘But it’s very useful,’ and he picked up his hairy uncle, the Baboon, by one hairy leg, and hove him into a hornet’s nest.

Then that bad Elephant’s Child spanked all his dear families for a long time, till they were very warm and greatly astonished. He pulled out his tall Ostrich aunt’s tail-feathers; and he caught his tall uncle, the Giraffe, by the hind-leg, and dragged him through a thorn-bush; and he shouted at his broad aunt, the Hippopotamus, and blew bubbles into her ear when she was sleeping in the water after meals; but he never let any one touch Kolokolo Bird.

At last things grew so exciting that his dear families went off one by one in a hurry to the banks of the great grey-green, greasy Limpopo River, all set about with fever-trees, to borrow new noses from the Crocodile. When they came back nobody spanked anybody any more; and ever since that day, O Best Beloved, all the Elephants you will ever see, besides all those that you won’t, have trunks precisely like the trunk of the ‘satiable Elephant’s Child.

Perhaps it seems natural and even proper to beat one’s children if one was beaten as a child. As Kipling’s story suggests, however, even in an era when spanking was entirely taken for granted, it built up deep resentment. Is there anyone willing to argue that this is healthy?

In the story’s conclusion, we are told that “nobody spanked anybody any more.” Dare to dream.

One Trackback

[…] one thinks of Peterson’s actions—I find them abhorrent—the union has a case that regular procedures must be in place, not only to protect NFL players […]