Monday

The rise of white terrorism around the world is leading liberals like me to question some of our basic assumptions. Are our democratic institutions, which we took for granted, strong enough to withstand the murderous resentment of entitled people who feel threatened? Amongst the entitled I include both those wealthy individuals who countenance violence (or at least extremist threats) to retain their privilege and those not-so-wealthy whites who use racism to shore up their self-esteem.

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness features a man who ascribes to humanist Christian values until he enters the Belgian Congo, at which point his ideals drop away and he becomes a bloody tyrant. Conrad has been rightfully criticized for his racism, but as far as diagnosing a naive optimism in liberal democracies, he may be on to something. What if liberals are like Kurtz’s Intended or the narrator’s Aunt, two women who can’t acknowledge the depth of darkness within their fellow human beings. The cynical Marlow describes his aunt’s vision of him as an emissary of light who will bring Christian civilization to the great unwashed:

It appeared, however, I was also one of the Workers, with a capital—you know. Something like an emissary of light, something like a lower sort of apostle. There had been a lot of such rot let loose in print and talk just about that time, and the excellent woman, living right in the rush of all that humbug, got carried off her feet. She talked about ‘weaning those ignorant millions from their horrid ways,’ till, upon my word, she made me quite uncomfortable. I ventured to hint that the Company was run for profit.

“’You forget, dear Charlie, that the labourer is worthy of his hire,’ she said, brightly. It’s queer how out of touch with truth women are. They live in a world of their own, and there has never been anything like it, and never can be. It is too beautiful altogether, and if they were to set it up it would go to pieces before the first sunset. Some confounded fact we men have been living contentedly with ever since the day of creation would start up and knock the whole thing over.

We can charge Marlow with patronizing sexism along with colonialist racism, but haven’t Americans been guilty of a comparable missionary zeal? Haven’t we thought that our democratic values would spread to all corners of the globe? For that matter, don’t we liberals think that it’s just a matter of time before a majority of all Americans transcend prejudice and accept African Americans, Hispanics, LBGTQ persons, and others different from themselves? Children of the Enlightenment that we are, don’t we assume that most people are decent at their core and that the light of reason will bring about something close to the society we dream of? Wasn’t this the vision of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and other founding fathers?

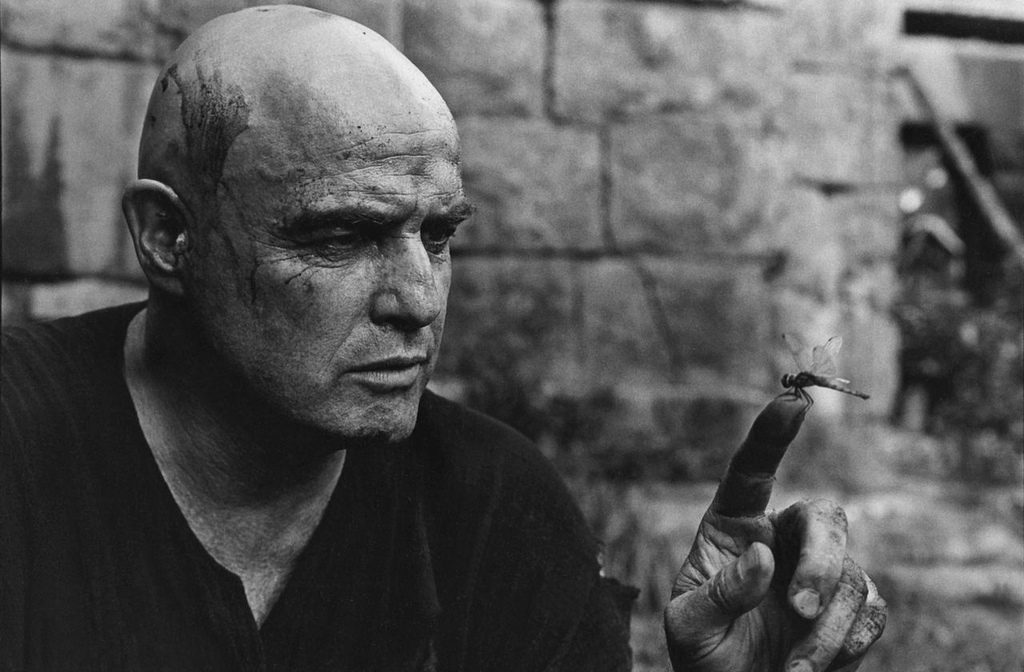

The resurgence of white terrorism and the corresponding rise of authoritarian states call our liberal optimism into doubt, as Robert Kagan writes in an important Washington Post article. Trump is like Kurtz unleashed in the Congo, causing us, like Marlow, to question our bearings. What if a significant number of Americans don’t care about democratic values? What does it mean that so many enthusiastically support a man who compliments extremists, calls for violence himself, and expresses admiration for autocrats?

If we liberals are like the out-of-touch women, Trump’s supporters are like Kurtz’s Russian follower:

‘We talked of everything,’ he said, quite transported at the recollection. ‘I forgot there was such a thing as sleep. The night did not seem to last an hour. Everything! Everything!… Of love, too.’ ‘Ah, he talked to you of love!’ I said, much amused. ‘It isn’t what you think,’ he cried, almost passionately. ‘It was in general. He made me see things—things.’

At one point Kurtz threatens to kill his fan, but that only deepens the man’s love. After all, what’s not to admire about a man who peremptorily demands obeisance? The Russian is like those Trump voters who continue to support him, even as they lose medical coverage, see their farms go bankrupt, and get hammered by his trade policies:

It was curious to see his mingled eagerness and reluctance to speak of Kurtz. The man filled his life, occupied his thoughts, swayed his emotions. ‘What can you expect?’ he burst out; ‘he came to them with thunder and lightning, you know—and they had never seen anything like it—and very terrible. He could be very terrible. You can’t judge Mr. Kurtz as you would an ordinary man. No, no, no! Now—just to give you an idea—I don’t mind telling you, he wanted to shoot me, too, one day—but I don’t judge him.’ ‘Shoot you!’ I cried ‘What for?’ ‘Well, I had a small lot of ivory the chief of that village near my house gave me. You see I used to shoot game for them. Well, he wanted it, and wouldn’t hear reason. He declared he would shoot me unless I gave him the ivory and then cleared out of the country, because he could do so, and had a fancy for it, and there was nothing on earth to prevent him killing whom he jolly well pleased. And it was true, too. I gave him the ivory. What did I care! But I didn’t clear out. No, no. I couldn’t leave him.’

And who is the man who inspires such devotion? Marlow describes a narcissist who can’t stop talking about his own greatness:

“Kurtz discoursed. A voice! a voice! It rang deep to the very last. It survived his strength to hide in the magnificent folds of eloquence the barren darkness of his heart. Oh, he struggled! he struggled! The wastes of his weary brain were haunted by shadowy images now—images of wealth and fame revolving obsequiously round his unextinguishable gift of noble and lofty expression. My Intended, my station, my career, my ideas—these were the subjects for the occasional utterances of elevated sentiments. The shade of the original Kurtz frequented the bedside of the hollow sham, whose fate it was to be buried presently in the mould of primeval earth. But both the diabolic love and the unearthly hate of the mysteries it had penetrated fought for the possession of that soul satiated with primitive emotions, avid of lying fame, of sham distinction, of all the appearances of success and power.

“Sometimes he was contemptibly childish. He desired to have kings meet him at railway-stations on his return from some ghastly Nowhere, where he intended to accomplish great things.

I’d drop the “unextinguishable gift of noble and lofty expression” when describing Trump, but everything else applies pretty well.

Kurtz, however, has what Marlow regards as a redeeming moment: right before he dies, he looks back at his life and is appalled at what he sees, crying out, “The Horror.” I’m not convinced that Trump is capable of such introspection, even on his deathbed. While he himself might regard comparison with Kurtz as a compliment, I think he’s more like one of T. S. Eliot’s hollow men, whom Eliot contrasts with the Kurtzes of the world.

So far, thankfully, our democratic institutions appear to be holding and Trump is not posting the heads of his enemies on stakes around the White House. We must remain vigilant, however.