Tuesday

From the moment I learned about Mary Trump’s forthcoming book on the Trump family, I searched for literary equivalents. Dickens’s Bleak House came to mind, but reader Donna Raskin has settled on a far better parallel: Jane Smiley’s Pulitzer Prize-winning A Thousand Acres. Given the number of people who have found similarities between Trump and Lear (for instance, here), it makes sense that Donna would conclude that a novel inspired by Shakespeare’s play captures the dysfunction described by Mary Trump.

Donna, an adjunct writing professor at the College of New Jersey and a program manager at The Lawrenceville School, is writing her first novel. She recently had a short story published in the Schuylkill Valley Journal.

By Donna Raskin

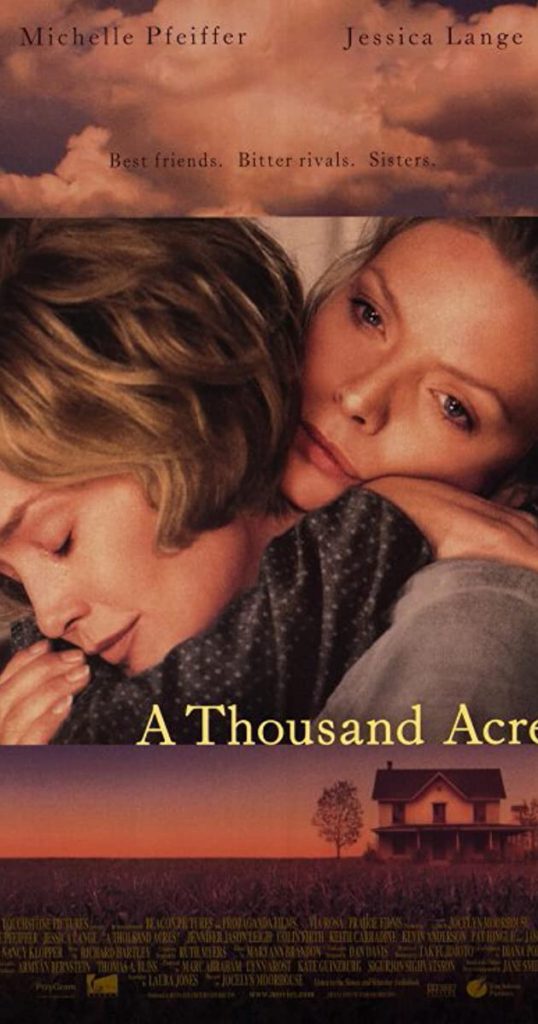

Throughout this current presidency, I have waited for the women closest to Donald Trump to speak up honestly and with courage about his criminally inappropriate behavior. Shouldn’t his wife have left him after she heard him bragging about aggressively grabbing women without their consent or for cheating on her after she had a baby? His wife and daughter’s silent acquiescence has brought to mind the sisters in Jane Smiley’s 1991 novel A Thousand Acres.

A Thousand Acres is an intimate story of one family, begun in the spirit of King Lear. When read against today’s political backdrop, however, it appears an interesting variation on the personality cult that is the Trump family, at least according to niece Mary Trump’s just released Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man.

In Smiley’s novel, Larry Cook transfers the ownership of his 1000 acres to his three daughters in order for them to avoid paying taxes after his death. The youngest daughter, who has left farm life and become a lawyer, does not agree with the plan and is cut out of the scheme, which instigates the immediate wrath of her father, although she eventually becomes the beloved. Each member of the family withholds secrets from the others, and the family itself hides secrets from the community. The real story, however, is the relationship between the two oldest sisters, Ginny and Rose, who have suffered mightily at the drunken, sexually violent hands (and other body parts) of their father.

Larry Cook, a petty, mean, and impulsive man who rules the family and the town through sexism and arrogance, sees everyone and everything through financial terms and his own needs. The two sisters and their husbands have spent their lives demonstrating their loyalty to a man who has never shown them love or kindness. As Rose observes,

Daddy thinks history starts fresh every day, every minute, that time itself begins with the feelings he’s having right now. That’s how he keeps betraying us, why he roars at us with such conviction.

This description, so similar to Mary Trump’s of description the president, keeps these sisters silent. Unlike them, however, the niece dissects her uncle’s sociopathic narcissism. As a highly educated psychologist, she has told the details of his parents and grandparents and the story that created the most powerful man in the world: immigrant and absent mothers, angry and scheming fathers, and deathly competitiveness between siblings, as well as (almost as an afterthought) sexism and greed. Like Rose Cook, Smiley’s middle sister, Mary is angry and wants to “bring down” her uncle.

“We’re not going to be sad,” Rose says. “We’re going to be angry until we die. It’s the only hope.”

Unfortunately, unlike Rose in the novel and Mary in real life, many women (and their husbands) are more than willing to smile politely while observing the horrifying behavior of men in power. Ginny, the eldest sister, has blocked out what their father did and only eventually is able to recover the truth. For much of the novel she is numb, subservient, and a victim of the trauma she has experienced. She describes her silence as “what it feels like to resist without seeming to resist, to absent yourself while seeming respectful and attentive.”

Like the Trump women until Mary, the Cook sisters understand their role. As Ginny explains,

It was imperative that the growing discord in our family be made to appear minor. The indication that my father truly was beside himself was the way he had carried his argument with us to others. But we couldn’t give in to that—we were well trained. We knew our roles and our strategies without hesitation and without consultation. The paramount value of looking right is not something you walk away from after a single night. After such a night as we had, in fact, it is something you embrace, the broken plank you are left with after the ship has gone down.

Fortunately, Mary has chosen to take control of the narrative. She has owned her anger and she has explained her disgust. Her story is not a surprise to those of us who disagree with the president’s point of view, which is centered around racial (white) and gender (male) superiority. I suspect that, like the townspeople of Zebulon County who continue to support Larry Cook after he calls his daughters bitches and whores at a community picnic, the presidents’ followers will not care a bit about her revelations because they support his behavior. They agree with it.

Nevertheless, as Rose says, “[A]ll I have is the knowledge that I saw! That I saw without being afraid and without turning away, and that I didn’t forgive the unforgivable.”