Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Thursday

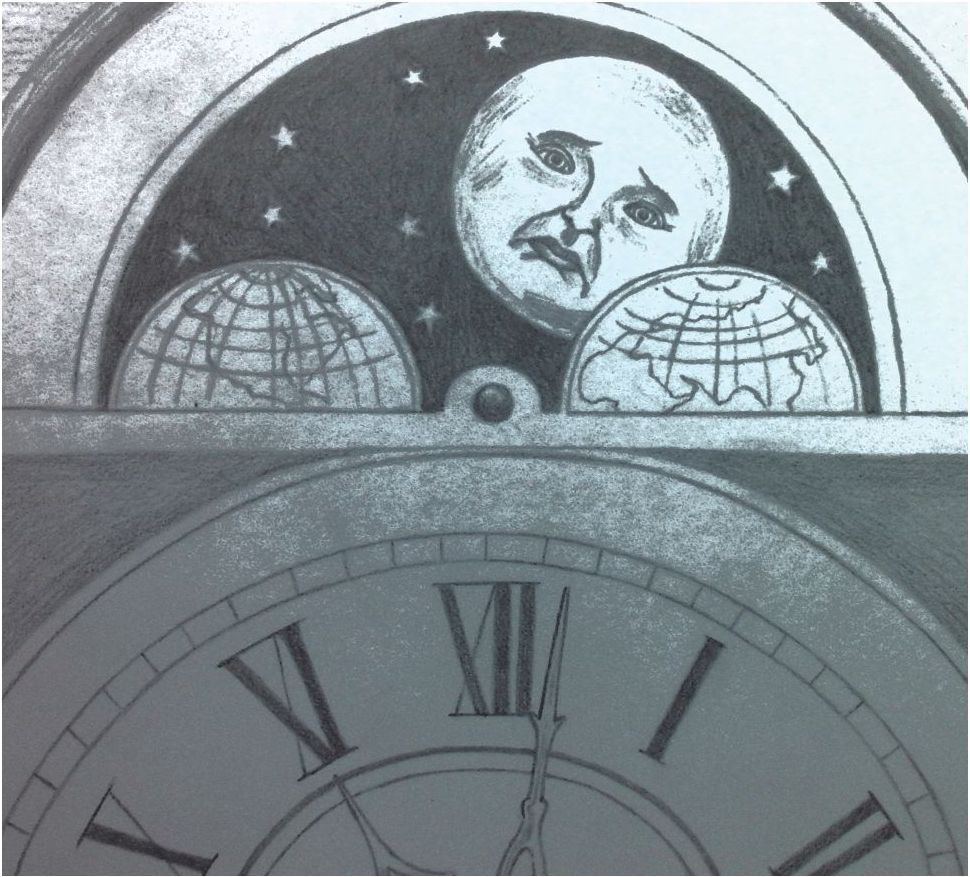

I know that W.H. Auden’s poem “Stop All the Clocks” is about the death of a loved one, but watching the dream of a multicultural democracy take a severe beating from a fascist is like witnessing the death of someone precious to us. So here’s the poem, which captures our agony as we watched our fellow citizens choose a rapist, felon, and insurrectionist over a classy woman who wanted to serve the people. At moments like this, a despairing lyric like this one can provide a modicum of relief.

While I know that, in the days to come, we will need to rally our forces and fight the good fight, for the moment it feels as if, indeed, “nothing now can ever come to any good.”

Stop All the Clocks

By W. H. Auden

Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone,

Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone,

Silence the pianos and with muffled drum

Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come.

Let aeroplanes circle moaning overhead

Scribbling on the sky the message He Is Dead,

Put crepe bows round the white necks of the public doves,

Let the traffic policemen wear black cotton gloves.

He was my North, my South, my East and West,

My working week and my Sunday rest,

My noon, my midnight, my talk, my song;

I thought that love would last for ever: I was wrong.

The stars are not wanted now: put out every one;

Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun;

Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood;

For nothing now can ever come to any good.

And for good measure, here’s a bonus poem–by the sublime Emily Dickinson–which ends on a slightly more hopeful note. But only because it reminds us that there is a future.

For a day after experiencing the great pain, it felt indeed like we were just going through the motions. Mechanical? Leaden? In a stupor? Frozen? Our nerves sitting like tombs? Check, check, check, check, and check.

“He that bore” could be Christ or it could be a soldier killed while bearing a backpack (the poem was written during the Civil War). In either case, there’s intense grieving. But the poet also holds out the possibility that we mourners can outlive this and achieve the final stage of grief, which is letting go.

After great pain, a formal feeling comes –

The Nerves sit ceremonious, like Tombs –

The stiff Heart questions ‘was it He, that bore,’

And ‘Yesterday, or Centuries before’?

The Feet, mechanical, go round –

A Wooden way

Of Ground, or Air, or Ought –

Regardless grown,

A Quartz contentment, like a stone –

This is the Hour of Lead –

Remembered, if outlived,

As Freezing persons, recollect the Snow –

First – Chill – then Stupor – then the letting go –

Once we let go, we can begin to re-engage with the world. As Edgar in King Lear reminds us, “The worst is not so long as we can say ‘This is the worst.’“