4th of July

I repost this essay from six years ago because it’s more relevant than ever given the Trump administration’s wholesale attacks on immigrants. No descendant of an immigrant (i.e., all Americans other than the descendants of Native Americans and slaves) has any standing to deny entrance to recent asylum seekers. Unless they are making white supremacist arguments (and many are), their argument usually boils down to, “We got here before you did so piss off.”

Of course, if previous generations had behaved the same way, these immigration opponents wouldn’t be here.

I think of a passage from Carl Sandburg’s “The People, Yes,” which is about land ownership but applies equally well to immigration:

“Get off this estate.”

“What for?”

“Because it’s mine.”

“Where did you get it?”

“From my father.”

“Where did he get it?”

“From his father.”

“And where did he get it?”

“He fought for it.”

“Well, I’ll fight you for it.”

Undoubtedly, the doctrine of “might makes right” has played a major role in history. But those who believe that we should strive for something higher will find a powerful argument in Gregory Djanikian’s “Immigrant Picnic,” where we sense how culturally barren we would be if we insisted on xenophobic purity.

Reprinted from July 4, 2012

The immigrant experience is, among other things, an experience involving language. Idiomatic expressions, invisible to native speakers, take on surprising associations for someone raised speaking a foreign tongue. In Gregory Djanikian’s humorous July 4 poem, we see the poet and his family getting their idioms slightly wrong and then running with the images that are opened up.

Born in 1949 to Armenian parents, Djanikian was raised in Cairo and immigrated to the United States when he was eight. The poem starts with him seemingly acculturated—he’s in charge of a backyard barbecue—but then discovers cracks in the facade. “On a roll” makes the picnic goers think of hamburger rolls and then the decidedly non-Armenian polka song “Roll out the Barrels.” The misquoted “you could grow nuts” sends the poet back to his childhood and the delicious nuts of Egypt. Just as immigrants have enriched the American diet (macaroni, hamburgers, and Bermuda onions are part of this feast), so (as Djanikian has noted) “unexpected syntactic constructions” and “surprising turns of phrase” have enriched American English.

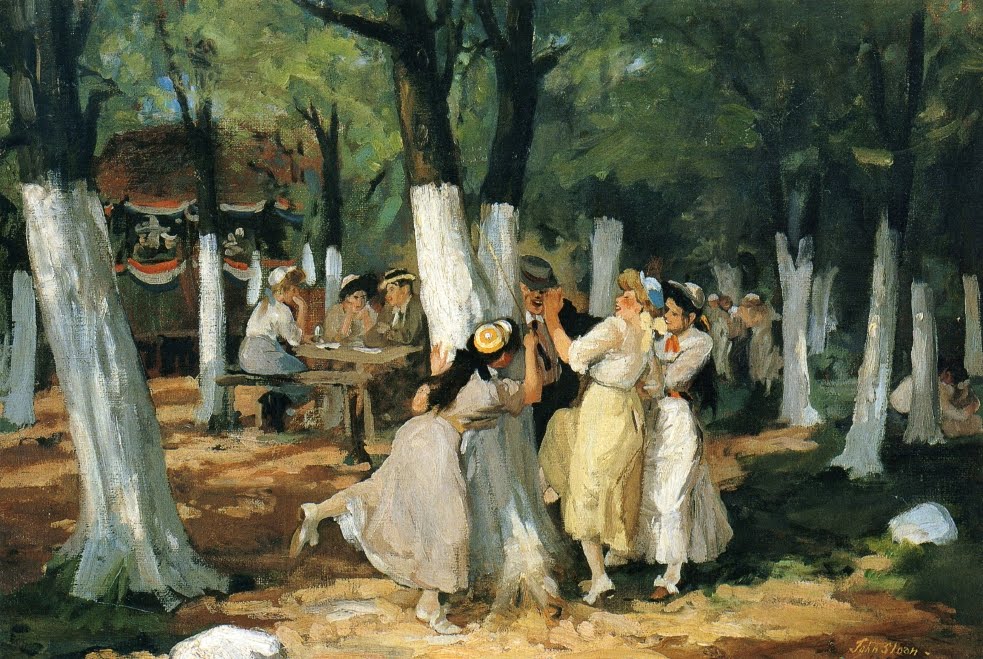

For all the anti-immigrant sentiment that has arisen in America in recent years, this cultural mixing is what defines us as a people. “Melting pot” fails to do it justice, so some have used the analogy of a salad bowl, some of an Irish stew. Now Djanikian has added mixed nuts. Today is a good day to celebrate this diversity.

Immigrant Picnic

By Gregory Djanikian

It’s the Fourth of July, the flags

are painting the town,

the plastic forks and knives

are laid out like a parade.

And I’m grilling, I’ve got my apron,

I’ve got potato salad, macaroni, relish,

I’ve got a hat shaped

like the state of Pennsylvania.

I ask my father what’s his pleasure

and he says, “Hot dog, medium rare,”

and then, “Hamburger, sure,

what’s the big difference,”

as if he’s really asking.

I put on hamburgers and hot dogs,

slice up the sour pickles and Bermudas,

uncap the condiments. The paper napkins

are fluttering away like lost messages.

“You’re running around,” my mother says,

“like a chicken with its head loose.”

“Ma,” I say, “you mean cut off,

loose and cut off being as far apart

as, say, son and daughter.”

She gives me a quizzical look as though

I’ve been caught in some impropriety.

“I love you and your sister just the same,” she says,

“Sure,” my grandmother pipes in,

“you’re both our children, so why worry?”

That’s not the point I begin telling them,

and I’m comparing words to fish now,

like the ones in the sea at Port Said,

or like birds among the date palms by the Nile,

unrepentantly elusive, wild.

“Sonia,” my father says to my mother,

“what the hell is he talking about?”

“He’s on a ball,” my mother says.

“That’s roll!” I say, throwing up my hands,

“as in hot dog, hamburger, dinner roll….”

“And what about roll out the barrels?” my mother asks,

and my father claps his hands, “Why sure,” he says,

“let’s have some fun,” and launches

into a polka, twirling my mother

around and around like the happiest top,

and my uncle is shaking his head, saying

“You could grow nuts listening to us,”

and I’m thinking of pistachios in the Sinai

burgeoning without end,

pecans in the South, the jumbled

flavor of them suddenly in my mouth,

wordless, confusing,

crowding out everything else.