Monday

While I no longer blog about film—there was just too much literature I wanted to write about—I make an exception with Citizen Kane, that most literary of movies. My most quoted scholarly article (you can find “Fiery Speech in a World of Shadows: Rosebud’s Impact on Early Audiences” if you google it) explores the rosebud symbolism and arrives at a similar conclusion to Netflix’s recent film about Citizen Kane’s screenwriter, but that’s not why I turn to it today. There’s a scene in the movie that all but predicts what we’re experiencing in our current presidential transition. Or should I say, non-transition?

First a quick note about the Netflix documentary. There has long been a debate about whether director Orson Welles or scriptwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz was most responsible for Citizen Kane, with Pauline Kael’s famous New Yorker article arguing for Mankiewicz and Welles scholar Robert Carringer counterarguing for Welles. (In my article, written with my father, I take an intermediate position: Welles, Mankiewicz and, for that matter, William Randolph Hearst were all obsessed with roses so that the rosebud symbol belongs to them all more or less equally.)

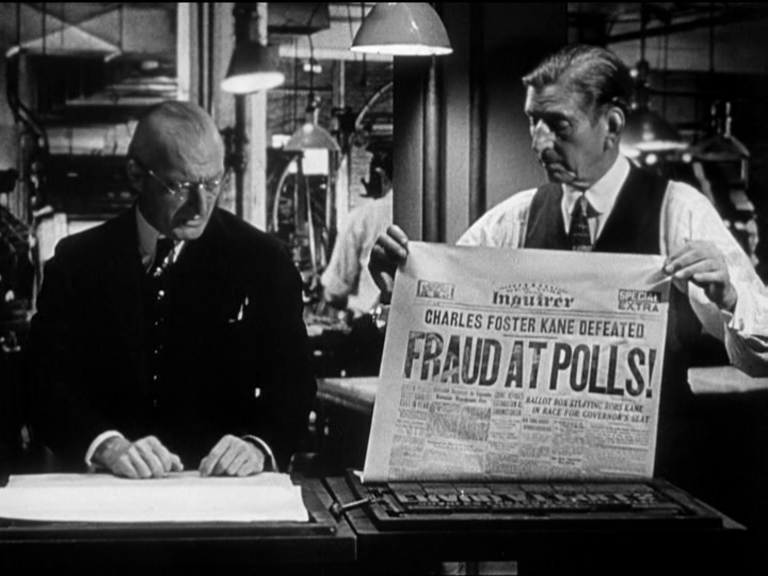

Back to the transition. Kane’s newspaper, awaiting the election result from his campaign for governor, has prepared two different front pages. The first headline announces Kane’s victory. The second screams, “Fraud at the Polls.”

Kane’s flunkies know that they must go with the second option when they learn that the only outstanding votes are those from boroughs with a heavy concentration of values voters. Apparently, there was a time when Christians might vote against you for significant character lapses, including adulterous affairs. How times have changed!

The “Fraud at the Polls” headline indicates that Kane thinks that, through his newspaper, he can manufacture his own reality. This doesn’t apply only to politics: he also thinks he can turn Susan Alexander into an opera diva. His best friend Jed Leland, displaying more spine than most members of the GOP, is fired when he tells the truth about her wretched singing. Charles Krebs, director of Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, suffered a similar fate after contradicting the president by announcing that “the November 3rd election was the most secure in American history.”

In 2016 I explored why Citizen Kane is Donald Trump’s favorite film, and the subsequent years have shown us many more parallels. The iconic still from the film, with a huge photo above Kane at the podium, shows that he uses crowds to feed his ego in the same way that Trump does. His rallies, like Trump’s, are opportunities to vent grievances rather than to put forth polices. Kane’s only campaign promise is to imprison his opponent. Lock him up!

Although Kane, like Trump, has cast himself as a populist, Leland exposes the claim. Kane doesn’t care about anyone but himself:

You talk about the people as though you owned them. As though they belong to you. As long as I can remember, you’ve talked about giving the people their rights as if you could make them a present of liberty, as a reward for services rendered.

Also, like Trump, Kane hobnobs with authoritarians—Mussolini, Franco and Hitler in his case—even while claiming to love democratic America. Like Trump, Kane has inherited millions and uses some of the money to build gaudy surroundings designed to prop up his fragile ego. Like Trump, he collects trophy wives.

It remains to be seen whether Trump has any rosebud poetry at his core. While I’ve compared Trump to King Lear, I’ve been skeptical that Trump can ever find the love that Lear discovers, Kane reconnects with his soul on his deathbed so perhaps Trump can as well. All three men cause a lot of misery before they reach that point, however.

Speaking of last-minute soul connecting, Dante shows how it works in Purgatorio. In Canto V Buonconte da Montefeltro, who took up arms against Dante’s beloved Florence, reports experiencing a heavenly moment before he dies. That is why, unlike his father—who had no such moment and therefore is in Inferno—Buonconte can make the afterlife journey from Purgatory to Paradise:

There my sight failed me, and my last word sped

Forth in the name of Mary; there headlong

I fell; there left only my body dead.

‘’Tis truth I speak: proclaim that truth among

Live men. God’s angel took me, and Hell’s fiend

Shrieked out: “O thief of Heaven, why do me wrong?

He’s thine—one tear, one little tear could rend

His deathless part away from me!”

For the sake of Trump’s own soul, I hope Citizen Kane being his favorite movie is a sign that somewhere, deep inside, he thrills to Kane’s rosebud moment. The snow globe, found when Kane is tearing apart Susan’s room, takes him back to the time when he was an innocent boy playing with his sled in New Salem, Colorado—a time before his loving mother betrayed him by selling him to a bank. Does Trump have within him that “one little tear”?

Or does he love the movie because he wants Kane’s celebrity status? Does he thrill only to the fact that Kane runs a media empire, is the constant center of attention, and has newsreels made about him when he dies. If so, he may be trapped forever in the self, just as Kane is trapped within those dark, ceilinged interiors. Or as Dante calls it, Inferno.

Further thought: Here another Welles-Trump connection. Apparently, Welles initially wanted to film Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here, about a fascist takeover of America. It was turned down as being too controversial–it would have offended RKO’s German audience–but that novel has seemed prescient in light of Trump attempts to overturn the election.

Welles also wanted to make Heart of Darkness, about a supposedly civilized and humane culture losing its way. Given the rise of authoritarian regimes in the 1930s, neither of these films projects is a surprise, but they show why a 1941 fictional biopic of a wannabe autocrat would resonate with us today.