Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Tuesday

In a recent New York Review of Books interview with the noted philosopher Martha Nussbaum, I came across this nugget about how Euripides came to her aid at an unbearably tragic moment:

I basically had a privileged and happy life up to the time I lost my daughter. My parents died, my marriage and several relationships ended, I didn’t get tenure at Harvard, but I always had a core confidence, stemming from my happy childhood, that I could prevail despite life’s tragedies. But I have also always had a very vivid sense of tragedy. I remember lying on the couch in our prosperous upper-middle-class house in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, reading Dickens—and later Tolstoy and Henry James, and of course the Greek tragedies themselves. In my imagination I was Hecuba and Clytemnestra. I was also an actress, both in school and, for a short time, professionally, and I tried to explore those roles in my own body. Even now, at the University of Chicago, we put on faculty productions, and I have played Clytemnestra opposite Richard Posner’s Agamemnon, and Hecuba surrounded by a wonderful cast of faculty friends in a production of The Trojan Women.

So my inner world had been prepared, almost rehearsed, for the biggest shock of my life, when my daughter died at the age of forty-seven, after a long illness, of a fungal infection after surgery. As she was dying I found myself in tears, hearing in my head Hecuba’s speech over the body of her grandson, when she says that she had always expected to die first, and all of a sudden she has to mourn this young child. I think that mental preparation was a kind of road map that made me less alone, and less clueless, in my grief.

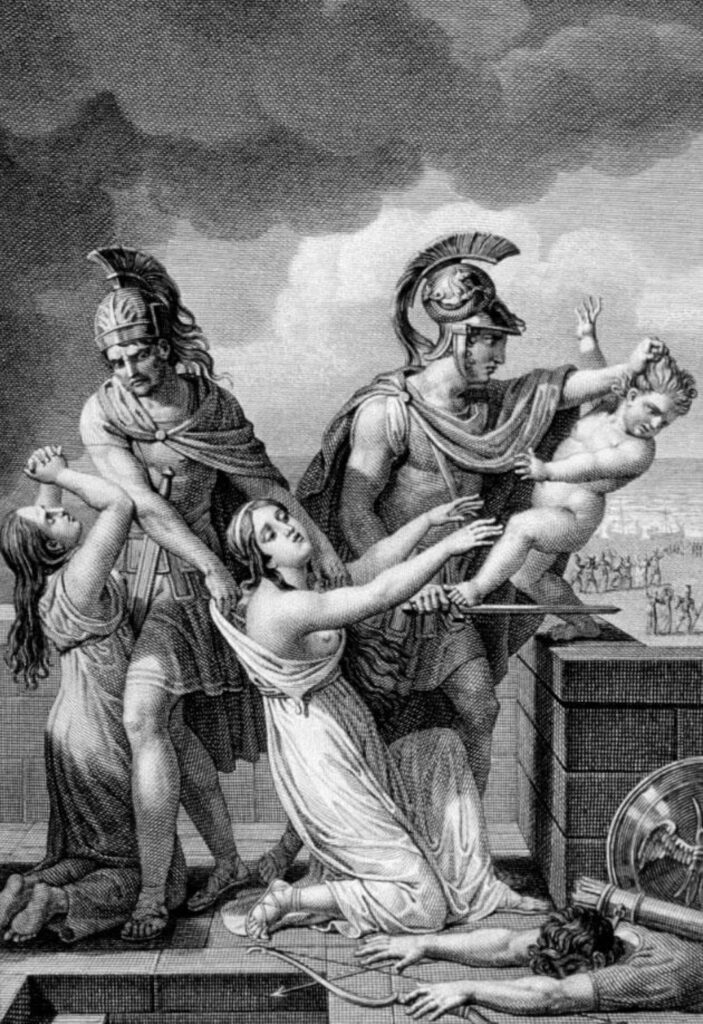

In addition to being deeply moved, I heartily agree with the observation that a lifetime of reading literature prepares one’s inner life, almost as a rehearsal, for tragedy when it strikes. It makes sense that Nussbaum, who dropped out of college for a short while to perform in New York productions of Greek tragedies, would think automatically of Hecuba mourning her grandson, whom the Greeks have thrown over the ramparts despite being only a baby.

In Euripides’s play, Hecuba has just been presented with Astyanax’s body, laid out on a shield. Her first words are bitterly sarcastic as she mocks the so-called bravery of warriors who feel the need to kill an innocent baby:

O ye Argives, was your spear

Keen, and your hearts so low and cold, to fear

This babe? ‘Twas a strange murder for brave men!

For fear this babe someday might raise again

His fallen land! Had ye so little pride?

While Hector fought, and thousands at his side,

Ye smote us, and we perished; and now, now,

When all are dead and Ilion lieth low,

Ye dread this innocent!

There is no wisdom behind the decision, she goes on to say, but only “that rage of fear that hath no thought.”

Having vented her fury at those responsible, she turns to the child, pointing to the irony that the high walls that were supposed to protect the Trojans have been the instrument of his death:

Poor little child!

Was it our ancient wall, the circuit piled

By loving Gods, so savagely hath rent

Thy curls, these little flowers innocent

That were thy mother’s garden, where she laid

Her kisses…

Hecuba goes on to remember a tender moment of togetherness. As Nussbaum notes (and as I, who have also lost a child, can confirm), there’s a special agony when the natural order is reversed and the child dies before the adult:

What false words ye said

At daybreak, when ye crept into my bed,

Called me kind names, and promised: ‘Grandmother,

When thou art dead, I will cut close my hair,

And lead out all the captains to ride by

Thy tomb.’ Why didst thou cheat me so? ‘Tis I,

Old, homeless, childless, that for thee must shed

Cold tears, so young, so miserably dead.

All that Hecuba can feel in this moment is absence:

Dear God, the pattering welcomes of thy feet,

The nursing in my lap; and O, the sweet

Falling asleep together! All is gone.

Then her anger and bitter sarcasm takes over again. This is how mourning works, with the mind swinging wildly between heartbreak and rage:

How should a poet carve the funeral stone

To tell thy story true? ‘There lieth here

A babe whom the Greeks feared, and in their fear

Slew him.’ Aye, Greece will bless the tale it tells!”

The speech ends with the irony of a prince’s son being buried in “poor garments,” along with a reflection—characteristic of the Greeks—on reversals of fortune and the vanity of human wishes. “Count no man happy until he is dead,” the historian Herodotus wrote, and Sophocles concludes Oedipus with the Chorus remarking, “[W]e cannot call a mortal being happy before he’s passed beyond life free from pain.” Euripides has a particularly bleak image, comparing fate (“the chances of the years”) to an idiot dancing in the wind:

Go, bring them—such poor garments hazardous

As these days leave. God hath not granted us

Wherewith to make much pride. But all I can,

I give thee, Child of Troy.—O vain is man,

Who glorieth in his joy and hath no fears:

While to and fro the chances of the years

Dance like an idiot in the wind! And none

By any strength hath his own fortune won.

When Nussbaum says that Hecuba’s speech provided her with “a kind of road map that made me less alone, and less clueless, in my grief,” she refers to stepping into the great community of suffering humanity that goes back to the beginning of time. I remember thinking along the same lines the night after we lost Justin—that this is what the poets, playwrights, and fiction writers had been referring to in all the books I had read.

It was a small comfort to realize that I now was one of them. When tragedy strikes, we may feel like a drowning victim thrashing around in the water, but literature provides us with images, characters, and words that we can grab onto, as though to a life raft.

Put another way, when we join with Hecuba in our grieving, we do indeed feel “less alone.” We see that people have trod this path before us, noble and heroic as they protest life’s sorrows, which means that we can trod it as well.

Literature as an essential survival kit to cope with the worst that life can throw at us.