Tuesday

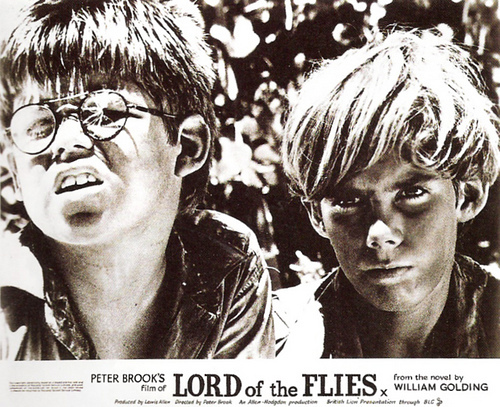

My English professor son alerted me to a fascinating Rutger Bregman Guardian article about a real-life Lord of the Flies incident with a different ending than Golding’s. In 1977 six boys from a boarding school in Tonga shipwrecked on a desert island and survived there for 15 months. There were no killings or savage rituals, however. According to the man who rescued them, they

set up a small commune with food garden, hollowed-out tree trunks to store rainwater, a gymnasium with curious weights, a badminton court, chicken pens and a permanent fire, all from handiwork, an old knife blade and much determination.”

Bregman observes that, “[w]hile the boys in Lord of the Flies come to blows over the fire, those in this real-life version tended their flame so it never went out, for more than a year.”

There were many other contrasts with the novel:

The kids agreed to work in teams of two, drawing up a strict roster for garden, kitchen and guard duty. Sometimes they quarreled, but whenever that happened they solved it by imposing a time-out. Their days began and ended with song and prayer. Kolo fashioned a makeshift guitar from a piece of driftwood, half a coconut shell and six steel wires salvaged from their wrecked boat – an instrument Peter has kept all these years – and played it to help lift their spirits. And their spirits needed lifting. All summer long it hardly rained, driving the boys frantic with thirst. They tried constructing a raft in order to leave the island, but it fell apart in the crashing surf.

Worst of all, Stephen slipped one day, fell off a cliff and broke his leg. The other boys picked their way down after him and then helped him back up to the top. They set his leg using sticks and leaves. “Don’t worry,” Sione joked. “We’ll do your work, while you lie there like King Taufa‘ahau Tupou himself!”

They survived initially on fish, coconuts, tame birds (they drank the blood as well as eating the meat); seabird eggs were sucked dry. Later, when they got to the top of the island, they found an ancient volcanic crater, where people had lived a century before. There the boys discovered wild taro, bananas and chickens (which had been reproducing for the 100 years since the last Tongans had left).

Bregman said that the experience better captures how humanity actually works:

For centuries western culture has been permeated by the idea that humans are selfish creatures. That cynical image of humanity has been proclaimed in films and novels, history books and scientific research. But in the last 20 years, something extraordinary has happened. Scientists from all over the world have switched to a more hopeful view of mankind. This development is still so young that researchers in different fields often don’t even know about each other.

Does this mean that Golding is wrong? I came across an intelligent twitter rebuttal by one Abigail Nussbaum, who argues that the point of Lord of the Flies

isn’t to illustrate what would “really” happen if a group of boys was cast away on an island, but to hold up a mirror to the processes that allow fascism to take hold in even “civilized” societies.

Regarding the “civilized” society Golding had in mind, his 1951 novel features

a particular type of post-War, barely-post-Empire, public-school-educated white English male. And it was written in response to colonialist fantasies starring such people. These fantasies all turn on the assumption of the inherent leadership qualities, the inherent “civilizing” effect of that particular class. That’s why the officer who rescues the boys is such a crucial character. He expresses that belief and expectation.

Golding doesn’t claim that all people are jerks, Nussbaum says, but rather that assholes like Jack can manipulate them. In his own time Golding witnessed the rise of Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini, and Franco, and we today, to our sorrow, have seen a number of authoritarian Jacks come to power.

Is Ralph and Piggy’s reasonable response enough to stop them? Civilized impeachment hearings weren’t enough to dislodge Donald Trump, and we’ll see what happens in the November election. Trump’s success so far, however, suggests Golding is on to something.

Nussbaum makes some other smart points:

It’s…worth noting that the Tongan castaways had various advantages the characters in LotF lack. They knew each other. They were friends (and thus presumably didn’t have a Jack amongst them). They apparently also had at least some wilderness skills. (They also had the weird good fortune of landing on an island whose previous inhabitants, stolen away by slavers, had left behind remnants of civilization that could be used for survival. Which in itself feels like an ironic commentary on colonialism.)

If Lord of the Flies has become a canonical part of high school English curricula, it’s because it strikes a deep chord. Those who are bullied and see their childhood innocence ripped away recognize its truth. I remember, as a senior, comparing Lord of the Flies to Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, concluding with Marlow’s rumination, “This too has been one of the dark places.” If I felt compelled to take this existential journey (I wrote the essay for myself, it wasn’t for any class), it’s because the issues were urgent. I identified with Ralph and Piggy because I shared their belief in decency and rationality.

Golding’s context was rising authoritarianism while mine was the racist American South and the Vietnam War. My whole life has been devoted to figuring out whether the highest achievements of culture—specifically literature—can prevail over barbarism. I took Golding’s book seriously because it provided a powerful challenge.

I don’t disagree with Bregman that humanity’s ability to cooperate is its “secret power.” This happens to be the central premise of my book How Beowulf Can Save America, which concludes with the inspiring vision of Beowulf and Wiglaf working together to slay the dragon. Golding’s dark perspective, however, makes us earn our optimism. The Jacks of the world will ruthlessly hunt down facile declarations of hope.