Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone. To unsubscribe, write here as well.

Wednesday

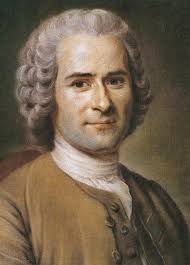

A close childhood friend, artist Tony Winters, gifted me a Wall Street Journal article that speaks to a number of my interests. Although I’m not convinced by Emily Finley’s claim that we should blame Jean Jacques Rousseau and Romanticism for a mental health crisis among today’s youth, I certainly subscribe to her belief that reading the classics can do some good. Here’s her argument:

She begins by citing Greg Lukianoff and Jonath Haidt’s Coddling of the American Mind, which contends that a culture of “safetyism” has made young people “less resilient and more anxiety-prone.” Haidt then argues, in The Anxious Generation, that “the widespread use of technology and social media is ‘rewriting’ childhood.”

Finley counters that parental coddling and technology addiction are symptoms, not causes, and that the real culprit is “the romantic corruption of imagination.” While she is as enthusiastic about the imagination as Rousseau and the Romantic poets–she regards it as “far more powerful than logic or reason” and a force that “colors our entire view of life and life’s possibilities”–she appears to hold Romanticism responsible for giving us a skewed vision of the world:

A malformed imagination is romantic. It is unbalanced and lacks proportion. It is oriented by an unrealistic, even utopian, vision of progress and a world altogether changed through human effort. This dreamy vision of a New Earth is made possible by the belief that “man is a naturally good being,” as the archromantic Jean-Jacques Rousseau declared in the 18th century. We must clear away the traditional religious and social norms hindering prosperity and instead heed the “cry of nature,” Rousseau argued.

The worldview Rousseau helped create, Finley says, “has played no small part in today’s mental-health crisis.” She bolsters her argument with a couple of ad hominem attacks, noting that the French philosophe placed five of his illegitimate children in orphanages—a particularly egregious move for a man who wrote one of the foundational texts on educating children—and that he was himself almost insane.

Instead of Rousseau-type imagination, Finley says, we need “a well-formed imagination” that is “properly adjusted to reality” and that “can adapt to life’s vicissitudes and see life steady and see it whole.”

So how does a malformed imagination contribute to the current crisis amongst young people. Finley says that it gives young people unrealistic expectations that are then dashed, leading to “melancholic despair”:

Having been told romantic tales from birth about their natural perfection and endless potential, young people can hardly be blamed for their unrealistic expectations. The modern childhood education is one great building up of the idea that, without any special effort, every child is going to be something extraordinary, and with their help, the world will be a better place. This is the romantic imagination’s manic side.

As these young people discover that they are, in fact, nothing very special, and that the world doesn’t appear to be improving despite their political crusading, they enter a period of melancholic despair. This is the romantic imagination’s depressive side.

So what should be guiding their imaginations? Finley cites religious beliefs, traditions, and standards, which would connect them with permanent things. And then—this is where we get to stories and poems—they need “good literature or history that would furnish their imaginations with examples of heroism, or even ordinary men and women overcoming the ordinary challenges of life.”

If modernity is not to be an Eliotian wasteland, Finley contends, what is required is

an immediate and total detox of the imagination. Instead of romantic lies and technological distractions, children must be nourished on works of imagination that provide concrete standards of what is worthy.

Finley is engaging here in the old classicism-romanticism debate—a version of the conservatism-liberalism debate—and coming down firmly on the side of the former. In actuality, however, there always needs to be a balance. Classicism without romanticism can be stultifying whereas romanticism without classicism can be (as she observes) ungrounded. It’s why every country needs conservative and liberal parties.

What it doesn’t need is a radically reactionary party in place of the conservatives, which is what we have currently.

With regard to literature, Finley recommends “old literature—written before about 1940,” implying that it is automatically superior. These old books, she says,

tell the extraordinary tale, to paraphrase G.K. Chesterton, of ordinary men and ordinary women and their ordinary children. Stories of family life, hardships, joys, challenges and the quotidian are the stuff that best orients young minds.

Far be in from me to critique the books that she mentions since they include some of my favorites. I don’t know Farmer’s Boy, but the others—I’m assuming she has in mind A Child’s Garden of Verses for Stevenson’s poetry—all sustained me as a child. I agree that this “feast of the imagination” teaches children “to have a realistic sense of what truly is possible in this life and wherein lie life’s boundaries” and that is helps us see “goodness and beauty, evil and ugliness for what they are”:

Laura Ingalls Wilder’s “Farmer Boy” shows children that in this life, reward comes after long, hard work. Frances Hodgson Burnett’s “The Secret Garden” illustrates what resilience looks like. C.S. Lewis’s “The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe” portrays the good and evil that lurk within each one of us. Greek myths teach children proportion. Robert Louis Stevenson introduces children to beauty in lyrical form.

At this point, however, Finley slips in a fast one, however. Apparently something—books written after 1940? the lingering effects of Rousseau and Romanticism?—is prompting young people to forsake “the ordinary duties of marriage and parenthood.” Instead, the focus is supposedly all about finding oneself and living as “an expressive individual.” She holds up Anna Karenina and Madame Bovary as examples of individual brought to misery by such romantic escapism.

To blame Rousseau for Anna Karenina’s behavior is a fairly one-dimensional view of her character. It’s not as though passionate, marriage-busting love is a Romantic invention. Are we to hold the French philosophe to account for Guinevere and Lancelot’s affair in the Malory’s Morte D’Arthur (1485). Or for Antony and Cleopatra’s ruinous engagement in Shakespeare’s 1606 play.

As for Emma Bovary, yes she is led astray by sentimental dreck: Bernardin de Saint-Pierre’s Paul and Virginia is essentially an 18th century Harlequin romance. Here’s Flaubert’s description of its impact:

Before marriage she thought herself in love; but the happiness that should have followed this love not having come, she must, she thought, have been mistaken. And Emma tried to find out what one meant exactly in life by the words felicity, passion, rapture, that had seemed to her so beautiful in books.

To give you a sense of what she’s reading, Flaubert mentions Emma dreaming of “the little bamboo-house, the Black slave Domingo, the dog Fidele, but above all of the sweet friendship of some dear little brother, who seeks red fruit for you on trees taller than steeples, or who runs barefoot over the sand, bringing you a bird’s nest.”

But the great Romantics, including some holding a utopian vision of progress, were highly critical of such shallow sentimentality. I’m particularly thinking of Percy Shelley who, revolutionary though he was, critiques Rousseau in The Triumph of Life for being trapped in his emotions and goes after shallow idealism in The Revolt of Idealism.

And as far as characterizing children’s book written after 1940 as all about finding and expressing oneself, has she read any of these books? Sure, there’s bad stuff, but that’s always been the case. It so happens, however, that we are living in a golden age of young adult literature featuring works that do indeed grapple with “family life, hardships, joys, challenges and the quotidian.” In fact, often they look more closely at married life than either Secret Garden or Narnia.

To say, categorically, that contemporary children’s literature fails to “separate the fruitless romantic dream from reality” is to reveal that one hasn’t read much contemporary children’s literature. With regard to parental upbringing, meanwhile, one could argue that children today are as likely to be ruined by hidebound traditionalists as by permissive progressives.