Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Thursday

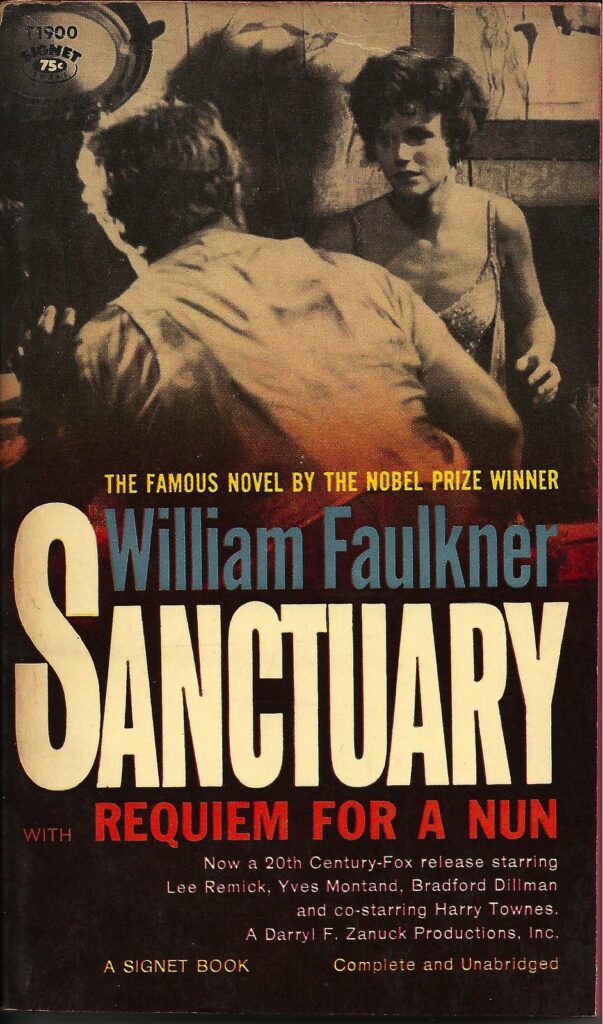

I’ve just completed another Faulkner novel and, as with Absalom, Absalom!, I find myself emerging from what feels like a hallucinatory nightmare. Sanctuary also seems particularly relevant for our current moment as we await word on whether Donald Trump will be indicted for his myriad alleged crimes, which include (I have to list them to get them clear in my mind) inciting an insurrection, pressuring lawmakers to change votes, assaulting a woman, stealing classified documents, defrauding the IRS, and paying hush money to a porn star to win an election. And yet, if Sanctuary is any guide, he could well get away with all of it.

That’s because Faulkner’s novel is about a great miscarriage of justice, in which an innocent man is found guilty of murder while the murderer—who also rapes a woman with a corncob and then kidnaps her and keeps her in a brothel as a sex slave—goes free. Part of Faulkner’s power resides in the way that everyone seems to exist in the grip of an inexorable machine that destroys them, along with any ideals about justice and fair play. Faulkner is where optimism goes to die.

For instance, when Horace Benbow assures his innocent client, Lee Goodwin, that he will go free, he fails to figure in corrupt behind-the-scenes dealmaking and the rape victim perjuring herself by fingering Goodwin, not her abductor. Then, as if to accentuate the injustice of it all, Goodwin is burned alive by a lynch mob, which is horrified by the corncob rape. The scene is one of gothic horror:

He ran into the throng, into the circle which had formed about a blazing mass in the middle of the lot. From one side of the circle came the screams of the man about whom the coal oil can had exploded, but from the central mass of fire there came no sound at all. It was now indistinguishable, the flames whirling in long and thunderous plumes from a white-hot mass out of which there defined themselves faintly the ends of a few posts and planks. Horace ran among them; they were holding him, but he did not know it; they were talking, but he could not hear the voices.

“It’s his lawyer.”

“Here’s the man that defended him. That tried to get him clear.”

“Put him in, too. There’s enough left to burn a lawyer.”

“Do to the lawyer what we did to him. What he did to her. Only we never used a cob. We made him wish we had used a cob.”

Horace couldn’t hear them. He couldn’t hear the man who had got burned screaming. He couldn’t hear the fire, though it still swirled upward unabated, as though it were living upon itself, and soundless: a voice of fury like in a dream, roaring silently out of a peaceful void.

I don’t know how many times over the past six years I’ve experienced Horace’s hope for justice, only to see Trump, time after time, escape accountability. Faulkner’s view of the world now seems truer to life, which may be one reason I’m drawn to it. Yoknapatawpha County justice seems closer to the justice system which saw Trump’s attorney general throw out the hush money charges against him, even though Trump fixer Michael Cohen went to jail for delivering the check. And the system that allowed this same attorney general to cover up evidence of the Trump campaign’s contact with Russia during the 2016 campaign and the presidential pardon system where Trump could pardon those associates took the rap for him. And, of course, the system where Congressional Republicans found Trump not guilty of (1) extorting a foreign leader to sling mud at his major rival and (2) inciting crowds to attack Congress.

Nor have violations of fair and impartial justice ended there. Currently we’re seeing Georgia Republican legislators drafting legislation that would allow them to fire any prosecutor bringing cases they don’t like, including Atlanta District Attorney Fani Willis indicting Trump for pressuring Georgia officials to change vote totals. (We’ve all heard the tape of him doing so.) And we’re seeing Congressional House Republicans overstep jurisdictional boundaries to threaten New York Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg for reviving at the state level the case that Trump’s attorney general quashed at the federal.

It’s so much simpler in Sanctuary, where it appears that the murderer’s lawyer has to do no more than pressure the woman to deliver false testimony. And then for her judge father to swoop in and, under a pretense of sensitivity, remove her from the court before she can be cross-examined.

Perhaps my current Faulkner fling has something to do with my own faltering idealism. In the past, my pessimism has also drawn me to the works of Flannery O’Connor and Cormac McCarthy, who have been undoubtedly influenced by Faulkner. In fact one sees the outlines of Sanctuary’s murderer in O’Connor’s Misfit (in “A Good Man Is Hard to Find”) and McCarthy’s Anton Chigurh (in No Country for Old Men). And indeed, when Faulkner writes a more cheerful book, as he did with The Reivers, I find myself put off. Faulkner described this novel as “a Golden Book of Yoknapatawpha County,” referring to the cheap children’s books once sold in grocery stores. Compared to the author’s previous books, it’s an apt description and consequently disappointing.

Pulled in as I am by Faulkner’s fatalism, I need a counterweight, which I find in the novels of Toni Morrison, even though she too has been influenced by the Mississippi author and employs some of the same gothic themes. But there’s a significant difference. With Faulkner (and O’Connor and McCarthy), I detect a disillusion with America’s founding ideals–their sense of tragedy appears to stem from America’s failure to live up to its promise–whereas Morrison’s Black characters know America too well to ever have had any illusions. They have their own battles between hope and despair, of course, but if they can find their way to some kind of transcendent hope in the end—I’m particularly thinking of Milkman in Song of Solomon and Sethe in Beloved—it’s because they have a firmer foundation for doing so. They’ve seen the worst America can do and have developed survival skills that the protagonists of the White novels lack.

So where does that leave us with prospective indictments of Trump? While we should continue to insist on justice—because without justice we are at the mercy of authoritarian rule—we should not despair if the courts fail to save us from our former president. Instead, we’ve just got to keep fighting, regardless of judicial outcomes. African Americans have learned the hard way not to put all their hopes in the court system and neither should we Whites. Faulknerian fatalism, compelling though it may be, is an indulgence we cannot afford.