Thursday

I recently received an eye-opening essay from a Pakistani student in my English 101: Composition and Literature class that sent my mind to Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. I’ll be taking a somewhat circuitous route to making the literary connection so sit down and prepare to enjoy the ride. I think you’ll find it as enlightening as I did.

Hamza Zia (who is allowing me to use his name and share his essay) is from a small town in Pakistan. He was raised in a small village with a substandard educational system so his ambitious father worked hard to purchase an internet connection. When Hamza found himself learning more from the internet than from school, he dropped out, which at first led to quarrels with his father. But his internet education proved so fruitful that he scored extremely high on the national O level examinations, at which point his father acknowledged that Hamza must know what he was doing and let him continue. His high scores earned Hamza further educational support and ultimately a scholarship to Sewanee.

His essay was about his culture shock upon arriving here. I share a slightly edited excerpt from his essay:

When we reached McClurg [Sewanee’s dining hall] I was surprised to see so much food and realized that I could eat as much as I wanted. It was like a buffet that was available every day. The variety was so much that it reminded me of a big grocery store…We [Hamza and his Vietnamese roommate] were very happy and excited about being university students and how good the university and dining hall were.

While I was eating, however, I looked around and saw that everyone else who was eating was using their phone or laptop. Everyone was talking to each other and the food itself was not important. It appeared to be invisible to everyone….It was like watching someone put petrol in their car.

Hamza reports feeling equally amazed—in fact, shocked—at how much food was thrown away. He notes that, when he was a child playing cricket near the garbage dumps, the kids would interrupt their game when the garbage trucks arrived to unload. The children usually didn’t find much but would “get very happy even about the small stuff.”

To further explain his shock, Hamza contrasted American eating practices with Pakistani:

When I was a kid, I was always taught that food and water are the most important thing in the world, and because they are so important we have to give them respect. If we do not, we will mess up our fortune and not get a lot of food in the future. When my family assembled for a meal, we would put aside distractions and sit on the ground and eat. Eating was like praying. It did not matter if it was my favorite food or food I did not enjoy eating. All food, even food we would put outside for birds, was respected. In Pakistan, if we ever drop food, we pick it up and kiss it and ask for forgiveness.

Hamza further noted that Pakistan differs from America in other ways as well:

In Pakistan we also do things slowly. Everything is relaxed and people do not worry about technical problems. People spend full days with their families and friends. Everyone does their work and then spends time doing whatever they like. I remember when I was growing up, my father and I would go outside two hours before the sunset, lying down on the grass and watching the eagles. We would do this almost every day. I would also go on walks with my uncle for three hours. We would go all over our town and then climb the hills nearby. There was no reason why we would watch eagles or go on long walks other than that we wanted to. Sometimes my father and I would go traveling to other towns on three day trips without any reason as well. We would just walk around, look at stuff, and talk to people. Life in Pakistan is very slow. It is like calm water.

These reminiscences led Hamza to a breakthrough understanding:

The reason why people don’t respect food over here is because there is another resource that is far more valuable than anything else to Americans. That resource is time. America is a rich country. That they can make tons of food is not be a big deal to them at all. But no matter how rich and advanced America is, it cannot make more time. So what matters the most to everyone is the amount of time they have. Because of this, everyone over here is in a hurry and trying to do as many things as possible in the smallest time possible. That’s why they work during their meals. Watching everyone in America go about their life is to me like watching a movie on 2x speed. If life in Pakistan is like calm water, life in America is like a very fast river with waterfalls.

His realization is helping Hamza “adjust to my new American life”:

The moral problem that I was facing [over wasted food] was solved because I understood the reasons why things are different over here. Because the economy and societal structure is so different in America, the morality I learned in Pakistan cannot be applied here…. You cannot judge and compare two things which have very different circumstances and say one is good and other is bad. This has also allowed me to keep my mind open and increased my wanting to learn new things. Every time I experience something different, I am excited because I try to understand the reasoning behind it and what made it be the way it is….This is how I have learned to live in American time.

Most of us will recognize what Hamza is talking about. In fact, there are those amongst us who actually boast that they eat their meals at their desks and that they work insane hours. Looking back, Americans can find signs of their current lifestyles in Defoe’s best-known novel. For Robinson Crusoe, working nonstop is a sacred duty. If you are idle, you are sinning against God.

Defoe was raised Puritan and his outlook has been traced to fundamentalist Protestantism in such groundbreaking works as sociologist Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905) and historian R.H. Tawney’s Religion and the Rise of Capitalism (1922). The argument goes something like this: early Protestants, especially the Calvinists, believed in predestination—which is to say that God, who knows everything, foresees who is going to be saved (the elect) and who is going to be damned. In other words, there is nothing one can do to change one’s fortune.

While we might think that this would give people the freedom to do whatever they want to do—after all, mere human effort makes no difference—the effect was instead the opposite. Because people were so anxious about their fate (hell, after all, was presented to them in the most graphic terms imaginable), they looked closely at their lives for reassuring signs that they were amongst the elect. Even the tiniest details were seized upon as evidence.

In pursuit of this reassurance, Puritans often kept meticulous journals. In his brilliant work The Rise of the Novel (1957), scholar Ian Watt argues that this focus is at the foundation of the English novel, which specialized in realism. In Defoe’s novel, we see Crusoe keeping a journal and noting things that characters in previous centuries would not consider worth mentioning. After all, we don’t know what Hamlet eats or how he dresses or any other of his daily habits. These things are not of interest to Shakespeare or his audience. That’s not the case with Crusoe.

So how is this related to Hamza and American time? After all, if it is decided ahead of time whether one is going to hell or to heaven, why not just lie on the ground and watch eagles soaring? Why not go on three-day trips seeing new sights and making new acquaintances?

People being people, however, the Puritans didn’t just observe. They also tried to ensure that the results of their lives proved they were amongst the elect. In other words, they worked hard to make sure that they got good results, that their journals were able to record successes. This may not make logical sense but it makes psychological sense. If they were making the most of the opportunities God had given them, they figured, then they were headed for the good place.

As a result, one finds in Puritan journals people chastising themselves for having slept for more than six hours and for wasting time. In Defoe’s novel Dickory Cronke, Ian Watt points out, the protagonist says at one point,

When you find yourself sleepy in a morning, rouse yourself, and consider that you are born to business, and that in doing good in your generation, you answer your character and act like a man.

Cronke even believes that to pursue economic utility is to imitate Christ:

Usefulness being the great pleasure, and justly deem’d by all good men the truest and noblest end of life, in which men come nearest to the character of our B. Saviour, who went about doing good.

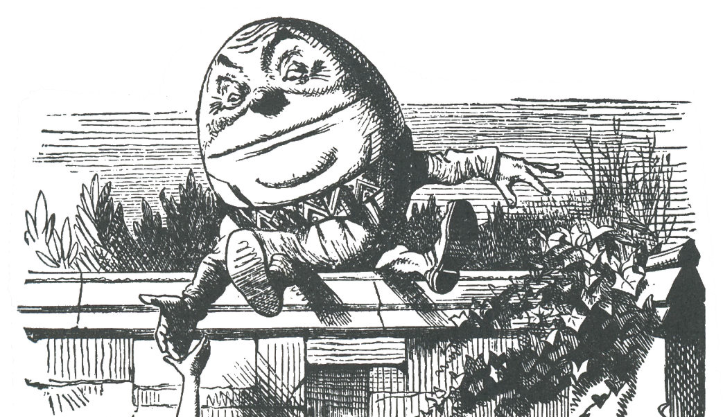

Crusoe, meanwhile, insists on never being idle. Unlike Hamza and his father, we never see him enjoying a sunset. Instead, we get such passages as this:

Thus, and in this disposition of mind, I began my third year; and though I have not given the reader the trouble of so particular an account of my works this year as the first, yet in general it may be observed that I was very seldom idle, but having regularly divided my time according to the several daily employments that were before me, such as: first, my duty to God, and the reading the Scriptures, which I constantly set apart some time for thrice every day; secondly, the going abroad with my gun for food, which generally took me up three hours in every morning, when it did not rain; thirdly, the ordering, cutting, preserving, and cooking what I had killed or caught for my supply; these took up great part of the day.

When Friday shows up in Crusoe’s life, Watt points out that the mariner doesn’t slow down. Instead, he sees it as an opportunity for accomplishing even more.

Calvinism first arrived in America through the Plymouth Rock Pilgrims, and the Protestant work ethic came to be known as the American work ethic. While it has dropped some of its religious trappings so that even non-religious Americans regard working hard as virtuous behavior, we see some of its religious origins in prosperity theology and in Norman Vincent Peale’s “the power of positive thinking.” In Peale’s church, economic success was a sign of God’s grace while failure was a sign that you were—if not damned—then at least unworthy. If you were poor, it was because you lacked faith and weren’t positive enough. In other words, being poor if your own fault, which is where some Americans oppose social safety net programs. Peale’s church, incidentally, was the one that the Trump family attended in the 1950s.

So to sum up: the “American time” that Hamza is witnessing has historical and religious origins. Defoe helped spread the vision in Robinson Crusoe, which for two hundred years was the most popular novel in Europe and America. Since then, the outlook has become so entrenched that Americans don’t even notice it anymore. It takes a student from a very different culture to make us aware of it.