Thursday

I recently finished reading Matthew Pearl’s The Dante Club, which has given me some new insights into the significance of Dante for 19th century American audiences. That’s because it’s set in 1867 Boston (right after the Civil War) at the time that Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was finishing up his famous translation of Divine Comedy. Dante Club is also a murder mystery and part of the plot involves the Harvard Board of Governors attempting to sabotage the translation, which they regard as dangerous.

The Dante Club in the novel includes Longfellow, fellow poets James Russell Lowell and Oliver Wendell Holmes, and legendary publisher James Taylor Fields, all of whom are assisting Longfellow in his translation. Lowell is also teaching a Dante class at Harvard, much to the consternation of the Board of Governors. In other words, the book reads like a literary Who’s Who of the age, with Ralph Waldo Emerson also making an appearance.

For today’s post, I share some of the passages from the book that cast light on the significance of Dante at the time. For instance, we hear about the objection of August Manning, treasurer of the Harvard Corporation:

Manning now thought about how to address the Dante problem. A staunch loyalist to classical studies and languages, Manning, it was said, spent an entire year conducting all his personal and business affairs in Latin…The living languages, as they were called by the Harvard fellows, were little more than cheap imitations, low distortions. Italian, like Spanish and German, particularly represented the loose political passions, bodily appetites, and absent morals of decadent Europe. Dr. Manning had no intention of allowing foreign poisons to be spread under the disguise of literature.

At one point, under orders from the Harvard Corporation, Harvard president Thomas Hill pressures Lowell to cancel his Dante class. Lowell, of course, will have none of it:

Lowell said he would not suffer the fellows of the Corporation to sit in judgment of a literature of which they knew nothing. And Hill did not even try to argue this point. It was a matter of principle for the Harvard fellows that they knew nothing of the living languages.

The next time Lowell saw Hill, the president was armed with a slip of blue paper on which was a handwritten quotation from a recently deceased British poet of some standing on the subject of Dante’s poem. “What hatred against the whole human race! What exultation and merriment at eternal and immitigable sufferings! We hold our nostrils as we read: we cover up our ears. Did one ever before see brought together such striking odors, filth, excrement, blood, mutilated bodies, agonizing shrieks, mythical monsters of punishment? Seeing this, I cannot but consider it the most immoral and impious book that ever was written.”…

Lowell laughed. “Shall we have England lord over our bookshelves….Till America has learned to love literature not as an amusement, not as mere doggerel to memorize in a college room, but for its humanizing and ennobling energy, my dear reverend president, she will not have succeeded in that high sense which alone makes a nation out of a people. That which raises it from a dead name to a living power.”

The Dante Club begins meeting in 1861, shortly after the commencement of the Civil War—which is to say, they have an inkling of a real life inferno to come. Longfellow at this point feels driven to translate the work. Lowell and Holmes discuss the project:

Lowell detailed for Holmes how remarkably Longfellow was capturing Dante, from the cantos Longfellow had shown him. “He was born for the task, I would rather think, Wendell.” Longfellow was starting with Paradiso and then would turn to Purgatorio and finally Inferno.

“Moving backwards?” Holmes asked, intrigued.

Lowell nodded and grinned. “I daresay dear Longfellow wants to make sure of Heaven before committing himself to Hell.”

“I can never go all the way through to Lucifer,” Homes said, commenting on Inferno. “Purgatory and Paradise are all music and hope, and you feel you are floating toward God. But the hideousness, the savagery, of that medieval nightmare! Alexander the Great ought to have slept with it under the pillow [instead of The Iliad].”

“Dante’s Hell is part of our world as much as part of the underworld, and shouldn’t be avoided,” Lowell said, “but rather confronted. We sound the depths of Hell very often in this life.”

The force of Dante’s poetry resonated most in those who did not confess the Catholic faith, for believers inevitably would have quibbles with Dante’s theology. But for those most distant theologically, Dante’s faith was so perfect, so unyielding, that a reader found himself compelled by the poetry to take it all to heart. This is why Holmes feared the Dante Club: He feared that it would usher in a new Hell, one empowered by the poets’ sheer literary genius. And, worse yet, he feared that he himself, after a life spent running away from the devil preached by his father, would be partially to blame.

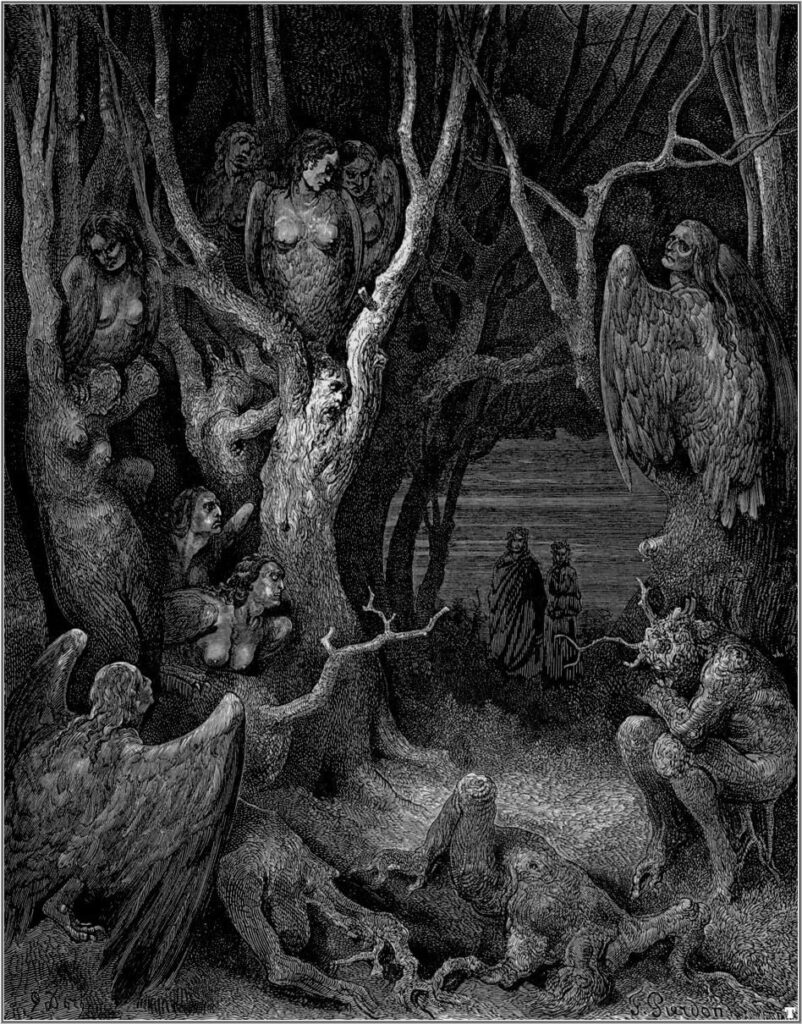

I love how Pearl describes the workings of the Dante Club. For instance, here they are discussing the wood of the suicides:

“In the seventh circle,” Longfellow said, “Dante tells us how he and Virgil come upon a black forest.” In each region of Hell, Dante followed his adored guide, the Roman poet Virgil. Along the way, he learned the fate of each group of sinners, singling out one or two to address the living world.

“The lost forest that has occupied the private nightmares of all of Dante’s readers at one time or another,” Lowell said. “Dante writes like Rembrandt, with a brush dipped in darkness and a gleam of hellfire as his light.”

Lowell, as usual, would have every inch of Dante at his tongue’s end; he lived Dante’s poetry, body and mind….

Longfellow read from his translation His reading voice rang deep and true without any harshness, like the sound of water running under a fresh cover of snow….

In the canto at hand, Dante found himself in the Wood of Suicides, where the “shades” of sinners have been turned into trees, dripping blood where sap belonged. Then further punishment arrived: Bestial harpies, faces and necks of women and bodies of birds, feet clawed and bellies bulging, crashed through the brush, feeding and tearing at every tree in their way. But along with great pain, the rips and tears in the trees provided the only outlet for the shades to utter their pain, to tell their stories to Dante.

“The blood and words must come out together.” So said Longfellow.

After two cantos of punishments witnessed by Dante, books were marked and stored, papers shuffled, and admiration exchanged. Longfellow said, “School is done, gentlemen. It is only half-past nine and we deserve some refreshment for our labors.”

And here’s one final passage, this one describing Lowell’s Dante class. Edward Sheldon is his most enthusiastic student. The passage begins by Lowell recalling a passage from Isaiah 38:10 in the Bible:

“Shall I translate [from the Latin]?” Lowell asked. “‘I say: In the midst of my days I shall go to the gates of hell.’ Is there anything our old Scripture writers didn’t think of? Sometime in the middle of our lives, we all, each one of us, journey to face a Hell of our own. What is the very first line of Dante’s poem?”

“‘Midway through the journey of our life,’” Edward Sheldon volunteered hapilly, having read that opening salvo of Inferno again and again in his room at Stoughton Hall, never having been so ambushed by any verse of poetry, so emboldened by another’s cry. “‘I found myself in a dark wood, for the correct path had been lost.’”

“‘Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita. Midway through the journey of our life,’” Lowell repeated with such a wide glare in the direction of his fireplace that Sheldon glanced over his shoulder…. “‘Our life.’ From the very first line of Dante’s poem, we are involved in the journey, we are taking the pilgrimage as much as he is, and we must face our Hell as squarely as Dante faces his. You see that the poem’s great and lasting value is as the autobiography of a human soul. Yours and mine, it may be, just as much as Dante’s.”

Lowell thought to himself as he heard Sheldon read the next fifteen lines of Italian how good it felt to teach something real.

That’s great literature for you. It’s something real.