Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at rrbates1951@gmail.com and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Monday

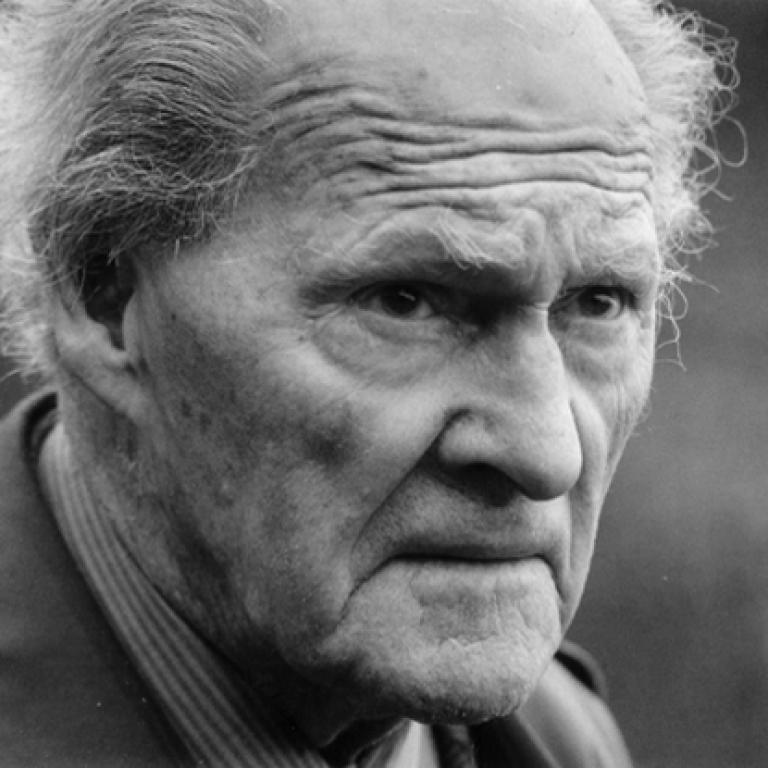

As this week sees the beginning of Sewanee’s Summer Writers’ Conference, I thought I’d reflect upon an enjoyable R.S. Thomas poem about the writing process. In “Poetry for Supper,” the Welsh writer imagines two poets arguing about whether poetry is more inspiration or perspiration.

It’s a question that people have been debating for at least as long ago as Plato, who in The Ion gets a performer of Homer’s poetry (a rhapsode) to admit that he is more an inspired receiver than a skilled craftsman. (Plato thinks this is bad although Ion seems fine with it.)

We have our own versions of the debate. Thomas Edison once said, when asked about his genius for invention, that “two percent is genius and ninety-eight per cent is hard work.” I’ve also heard (but don’t know the source) that “art is 10% inspiration, 90% perspiration.” And then there is Yogi Berra’s version: “Baseball is ninety percent mental. The other half is physical.”

Anyway, in Thomas’s poem the discussion is endless. But it at least gives the two poets a subject to occupy them as they share a beer (“the talk ran/ Noisily by them, glib with prose”). We see one poet taking a Keatsian position, the other a Chaucerian/Yeatsian position.

Poet #1 argues that

verse should be as natural

As the small tuber that feeds on muck

And grows slowly from obtuse soil

To the white flower of immortal beauty.

In saying this, he is playing off a Keats observation in an 1818 letter to his friend John Taylor:

The rise, the progress, the setting of Imagery should, like the sun, seem natural to [the poet], shine over him, and set soberly, although in magnificence, leaving him in the luxury of twilight. But it is easier to think what poetry should be, than to write it – And this leads me to another axiom – That if poetry comes not as naturally as the leaves to a tree, it had better not come at all.

Thomas’s poet here, like Thomas himself, is much more earthy than Keats. Still, the sentiment is the same.

The second poet responds by citing Chaucer, asking what the poet “said once about the long toil/ That goes like blood to the poem’s making?” In a fine discussion of the poem, the Guardian’s Carol Rumen speculates that this is a reference to The Parliament of Fowles, where Chaucer writes, “The Lyf so short, the craft so long to Lerne, / Th’assay so hard, so sharp the conquerynge.” But the poet may also be referring to the story that the Squire tells in Canterbury Tales, where the young man pleads an insufficient grasp of rhetorical figures to do justice to the woman whose beauty he wants to describe:

But to tell you all her beauty,

It lies not in my tongue, nor in my abilities;

I dare not undertake so high a thing.

My English also is insufficient.

He must be an excellent rhetorician

Who knows his figures of speech appropriate to that art,

If he should describe her in every detail.

I am none such, I must speak as I can.

Without such a grasp of the poetic craft, poet #2 argues,

the verse sprawls,

Limp as bindweed, if it break at all

Life’s iron crust.

Then comes the reference to Yeats’s “Circus Animals’ Desertion.” The “masterful images” that once came to the poet effortlessly have deserted him in his later years. To create new poems, he figures, he must reach into the recesses of his heart, which he describes as a rag and bone (junk) shop. From there, he must—perhaps painfully—build a ladder up to new poetic creations:

Those masterful images because complete

Grew in pure mind but out of what began?

A mound of refuse or the sweepings of a street,

Old kettles, old bottles, and a broken can,

Old iron, old bones, old rags, that raving slut

Who keeps the till. Now that my ladder’s gone

I must lie down where all the ladders start

In the foul rag and bone shop of the heart.

This is the ladder that Thomas’s Poet #2 references:

Man, you must sweat

And rhyme your guts taut, if you’d build

Your verse a ladder.

To which poet #1, returning perhaps to Keats and his naturally shining sun, replies:

You speak as though

No sunlight ever surprised the mind

Groping on its cloudy path.

Which elicits the response,

Sunlight’s a thing that needs a window

Before it enter a dark room.

Windows don’t happen.

And so on and on, ending on a note of gentle self-satire. Prose is glib because it thinks it can arrive at definitive answers where there are none to be had. For that matter, perhaps the poets would be spending their time more profitably if they were actually writing poetry rather than talking about how poetry is written.

Then again, it’s a harmless enough diversion from either the hard work of writing poems or the intuitive work of allowing them to flow through one. The fellowship is the real point.

Furthermore, as I can personally testify, talking about literature is endlessly satisfying. Here’s the poem:

Poetry for Supper

By R.S. Thomas

‘Listen, now, verse should be as natural

As the small tuber that feeds on muck

And grows slowly from obtuse soil

To the white flower of immortal beauty.’‘Natural, hell! What was it Chaucer

Said once about the long toil

That goes like blood to the poem’s making?

Leave it to nature and the verse sprawls,

Limp as bindweed, if it break at all

Life’s iron crust. Man, you must sweat

And rhyme your guts taut, if you’d build

Your verse a ladder.’

‘You speak as though

No sunlight ever surprised the mind

Groping on its cloudy path.’‘Sunlight’s a thing that needs a window

Before it enter a dark room.

Windows don’t happen.’

So two old poets,

Hunched at their beer in the low haze

Of an inn parlor, while the talk ran

Noisily by them, glib with prose.