Tuesday

My friend Rachel Kranz alerted me to this disturbing account on “How Prison Labor Is the New Slavery and Most of Us Unwittingly Support It.” She also reminded me about how she had described prisons as the new growth industry in her 2000 novel Leaps of Faith.

Leaps of Faith has proved prescient in a number of ways, including in its exploration of same sex marriage. Now that people in both political parties are finally expressing concern about how many people are incarcerated in America’s prisons, it’s worth looking back at what Rachel had to say 16 years ago.

First, here’s the situation as described by the article:

With 5 percent of the world’s population and 25 percent of the world’s prison population, the United States has the largest incarcerated population in the world. No other society in history has imprisoned more of its own citizens. There are half a million more prisoners in the U.S. than in China, which has five times our population. Approximately 1 in 100 adults in America were incarcerated in 2014. Out of an adult population of 245 millionthat year, there were 2.4 million people in prison, jail or some form of detention center.

The vast majority – 86 percent – of prisoners have been locked up for non-violent, victimless crimes, many of them drug-related.

And now for something you probably did not know:

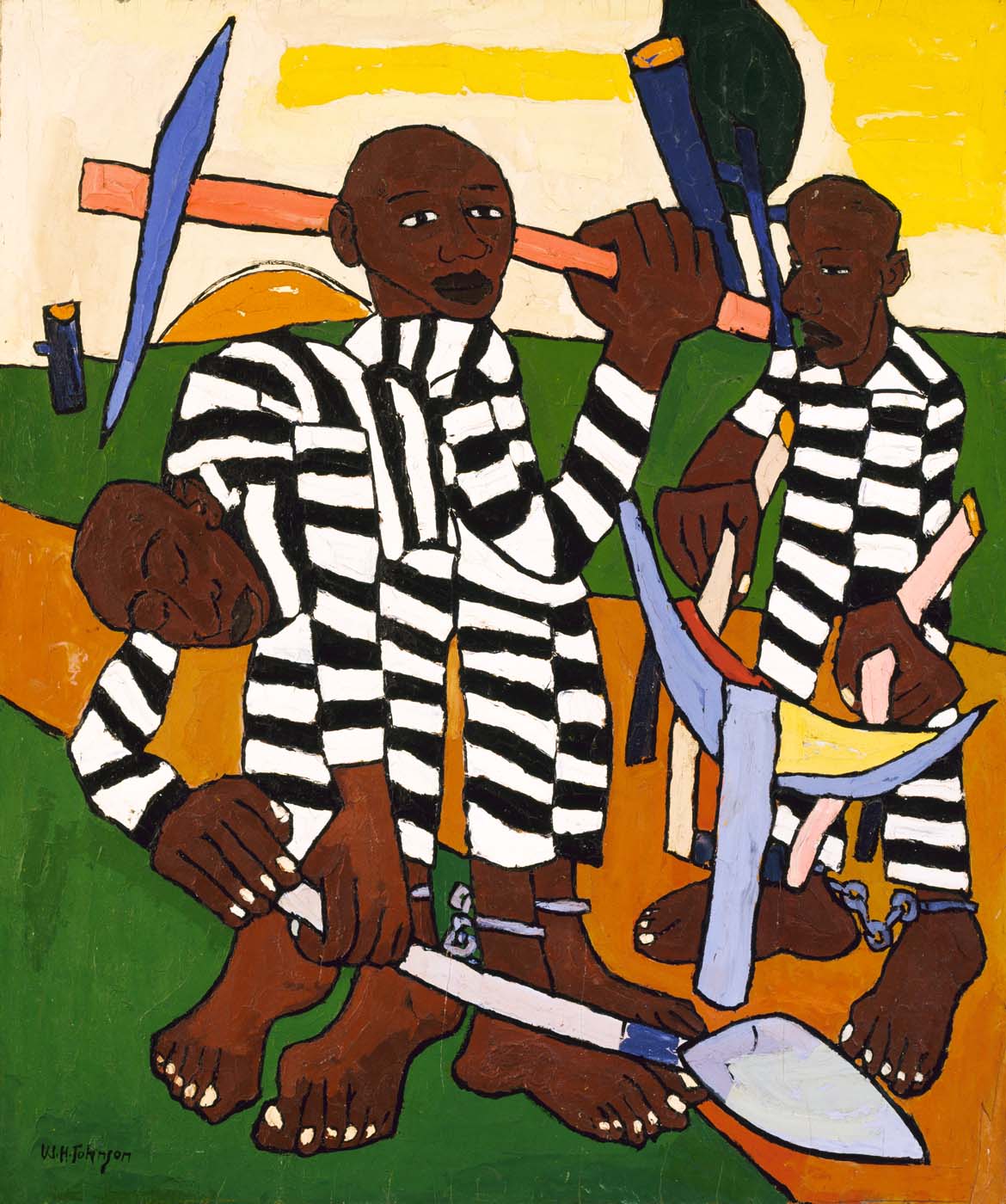

American slavery was technically abolished in 1865, but a loophole in the 13th Amendment has allowed it to continue “as a punishment for crimes” well into the 21st century. Not surprisingly, corporations have lobbied for a broader and broader definition of “crime” in the last 150 years. As a result, there are more (mostly dark-skinned) people performing mandatory, essentially unpaid, hard labor in America today than there were in 1830.

The article goes on to cite many of the companies taking advantage of prison labor, including Whole Foods, McDonald’s, Walmart, Victoria’s Secret, AT&T, and British Petroleum (to clean up its Gulf of Mexico oil spill). It’s a fascinating article.

Leaps of Faith doesn’t touch on unpaid, hard labor but it does discuss the prison boom. Flip, an actor who does temp work to pay the bills, at one point finds work with “TechnoMort,” which

is going into the prison business, the one true growth industry of the new millennium, along with computers, of course. But according to Georgia, my TechnoMort supervisor, who gives me an impassioned first-day orientation, computers are a capital-intensive industry that is unlikely to employ large numbers of human beings, since replacing human labor with machines is the whole point of computers. Whereas prison is a labor-intensive industry that promises to keep thousands if not millions of Americans gainfully employed for generations to come. Which means that if I don’t get an acting job soon, I should probably forget about learning Excel (which Tanya has been telling me to do) and just go get trained as a guard.

“It’s not just the prisons themselves,” Georgia explains earnestly as she leads me to a desk that looks remarkably like the one I had at [my previous job]. “It’s all the satellite industries. It’s been an economic renaissance for upstate New York, it really has. Because even if you don’t want to work as a guard or a cafeteria person or a social worker or a janitor or a—a—“

“A warden,” I suggest helpfully, drawing on my extenstive knowledge of old prison movies. But Georgia looks doubtful.

“Well, of course, they only have one warden per prison,” she says. “So I don’t think that profession would provide all that many jobs, I really don’t. But even if you didn’t work inside the actual prison, you could work for a food servicer company, or the company that does the laundry, or the one that trains the dogs, because all those services are now subcontracted out. And in Texas, and Ohio, and North Carolina, and lots of other places, they have private companies running the whole prison. So it’s not just expanding the public sector. It’s also expanding the private sector. Some of those communities, you go out there and you’ll find that pretty much every single person in town works for the prison.”

Georgia then recommends that Flip apply to work full-time for TechnoMort, sounding like a Donald Trump supporter as she does so:

“Because the salary is fairly good, and the benefits are truly excellent, and also, of course, you’d be performing a public service.” She switches on the computer. “Because,” she continues, “most of those criminals locked up upstate come from right here in New York City, so we should all be grateful that they’re not running around loose. Because otherwise—“

“So we supply the prisoners and they supply the prisons?” I say. “That seems fair.”

She looks at me sharply to be sure I’m not joking, but I try to keep a straight face and apparently I succeed.

“There’s a reason the prison industry is growing so fast,” Georgia says sternly. “Society is breaking down. These people have to go somewhere.”

I am trying really hard to keep a straight face.

“Well,” she says, “you live in the city, don’t you? So you know where the criminals come from. The vast majority come from just seven New York City neighborhoods, they really do, which would be all right if they stayed in those neighborhoods, but they don’t, they have to wander the streets and mug and rape and murder the rest of us, so I must tell you that I, personally, am extremely thankful that there are companies like TechnoMort that make it easier for communities—not just in New York, of course, but all over the country—to solve their security problems in the most cost-efficient way possible. Because, believe me, every dollar that they save on construction is a dollar that can go into enforcement and security, which means that once those people are behind bars, they stay behind bars, and I for one feel safer for it.”

This is probably one of the few times when “I’m sorry” actually isn’t the right response to a work-related conversation, so I just nod and try to look impressed. Georgia hurries off, promising to come back and check up on me in half an hour or so, and I look despairingly at the huge stack of forms. All over the country, apparently, city, county, and state officials are thinking about the most cost-effective way to build new prisons. Well, there’s a cheerful thought.

In a promising new development, the Justice Department this past month announced that it will stop using private prisons on the grounds that “the facilities are both less safe and less effective at providing correctional services than those run by the government.” That’s a small step in the right direction, even if it only will impact 22,000 prisoners. Unfortunately, the directive will not effect state prisons, where most prisoners of America’s prisoners are housed.

It does cast doubt on Georgia’s enthusiasm for TechnoMort, however. Some things you want the government to do.

And you don’t want anyone operating a slave system.