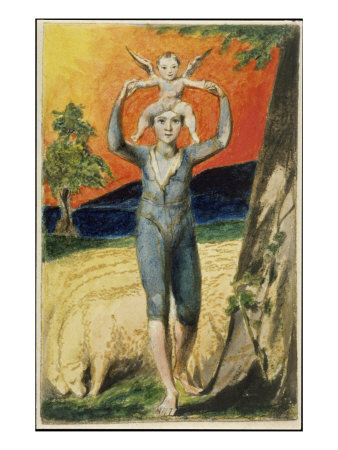

from Songs of Innocence and Experience

from Songs of Innocence and Experience

My Introduction to Literature class (focus on Nature) has just moved from Robinson Crusoe to William Blake, and we are seeing in the 18th century a conflict similar to one we are witnessing today over the environment. Defoe’s protagonist is an advocate of the “drill, baby, drill” approach to nature although, in his defense, Crusoe is not dealing with a planet in crisis. (His consumption of sea turtle eggs shocks us now.) Blake, on the other hand, sees a mystical and childlike spirituality in nature that we must reconnect with if we are to be healthy.

Although I have more sympathy with Blake’s vision, I have to admit to being impressed with the energy exhibited by Crusoe. The excitement of domination continues to galvanize anti-environmental forces, which is why they are able to get the traction they do. To be sure, as I wrote yesterday, we pay a spiritual and psychological cost when we cut ourselves off from nature, which in the novel manifests itself in the form of Crusoe’s paranoia and other pathologies. But domination still packs a punch and helps explain why those trying to slow global warming or fighti mountaintop removal are encountering such stiff populist resistance.

Our discussion in Monday’s class, however, focused less on environmental issues and more on questions of science and religion. Crusoe’s systematic approach to conquering the natural world was as much a part of the Age of Reason as science’s new confidence that it could crack the mysteries of the universe. Over a third of the students in the class are biology majors, so we discussed Blake’s attack on Enlightenment science. It was a discussion I was glad to see future doctors and researchers engaged in.

We looked closely at a poem where Blake takes on 18th century philosophers Voltaire and Rousseau, along with Newton and the Greek philosopher Democritus:

Mock on, mock on, Voltaire, Rousseau:

Mock on, mock on: ‘tis all in vain!

You throw the sand against the wind,

And the wind blows it back again.

And every sand becomes a Gem,

Reflected in the beam divine;

Blown back they blind the mocking Eye,

But still in Israel’s paths they shine.

The Atoms of Democritus

And Newton’s Particles of Light

Are sands upon the Red Sea shore,

Where Israel’s tents do shine so bright.

In the poem, Voltaire, Rousseau, Democritus and Newton represent blinkered science that believes reality to be merely physical. I’m not sure that Blake is doing entire justice to these men. Newton, after all, had a religious side, Voltaire was a critic as well as a practitioner of reason, and Rousseau, in addition to writing the Social Contract and devising a system of education for young Emile, also described (in “Reveries of a Solitary Walker”) an ecstatic out-of-body experience in nature. My biochemistry student Maria Concepcion pointed out that Blake may be unfairly caricaturing all scientists as narrow materialists.

So let’s just see him criticizing that strain within science, and within certain scientists, to conceptualize the universe as a vast machine. Unfortunately, as literary theorist Terry Eagleton points out in his book Reason, Faith and Revolution: Reflections on the God Debate, there are prominent scientists and thinkers today who are guilty of such thinking. Eagleton fingers British biologist Richard Dawkins, author of The God Delusion, and columnist Christopher Hitchins.

In Blake’s view of it, scientists trying to solve scientific enigmas are throwing theories, like so many handfuls of sand, at the mystery of creation. Creation, he says, merely blows them back. Were they to truly look at a single granule of this sand, they would discover a gem revealing the “gleam divine.”

This is an idea that Blake articulates even more memorably in the opening lines of Auguries of Innocence:

To see a world in a grain of sand

And a heaven in a wild flower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand

And eternity in an hour.

In “Mock on, mock on,” Blake continues with the sand metaphor. The particles of sand are like Democritus’s atoms or Newton’s particles of light, scientific theories that, in their effort to explain the universe, end up missing out on its holiness. Thus we have the clever image of the mockers being blinded by the particles while all around them lie the sands of the Red Sea shore, home to the Hebrew slaves following their miraculous escape from Egypt.

Does Blake persuade anyone who is not spiritually inclined? At least don’t dismiss him as a religious fundamentalist. He is just as hard on dogmatic religion as he is on materialistic science, as indicated in the following poem:

I went to the Garden of Love,

And saw what I never had seen:

A Chapel was built in the midst,

Where I used to play on the green.

And the gates of this Chapel were shut,

And “Thou shalt not” writ over the door;

So I turn’d to the Garden of Love,

That so many sweet flowers bore,

And I saw it was filled with graves,

And tomb-stones where flowers should be:

And Priests in black gowns were walking their rounds,

And binding with briars my joys & desires.

The innocent green and natural world where children used to play has been invaded by a chapel with “thou shalt not” written over the door. The flowerbed, meanwhile, has become a graveyard presided over by black-clad priests. And while these priests might stand in for the establishment church (Anglican, Catholic, take your choice), I suspect Blake would be just as hard on those fundamentalist sects (Christian, Jewish, Islamic) that want to bind with briars our joys and desires.

Juxtaposing Robinson Crusoe and William Blake sets in motion a complex conversation about the relationship of spirituality and science. Defoe’s systematic exploitation of nature is challenged by Blake’s longing for spiritual connection. The link in Robinson Crusoe between such exploitation and Crusoe’s fundamentalist Protestantism surfaces today in those fundamentalist Christian groups that are opposed to the environmental movement. Meanwhile Blake’s readiness to attack both enlightenment science and repressive religion anticipates the similarities that critics like Eagleton find between fundamentalist Christianity and fundamentalist secularism, despite the fact that each group sees the other as the archenemy.

My science students, some of whom are church-going, some of whom see themselves as spiritual but not religious, and some of whom are materialists, find images, narratives, and themes in these works that help them sort through issues that are important to them.

One Trackback

[…] with the environment. I examined how Blake, witnessing the damage caused by capitalism, seeks a spiritual connection with nature. I showed how such a connection, as envisioned by the Romantic poet William Wordsworth, can help […]