Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Wednesday

By re-electing a man who attempted a coup, the American electorate has challenged the world view of many of us. Heretofore we thought that, for all America’s flaws, its citizens would see through this gfiting crook, that justice would ultimately prevail, and that democracy would survive, self-correcting if things started going off the rails.

I’m aware that my own optimism is partly due to my privileged background. Other groups, especially African Americans and Native Americans, are less surprised them I am at recent developments. But it’s not only a life of privilege that has shaped my world view. I realize that my childhood reading has also contributed to my belief that all will come out right. Miss Prism in Oscar Wilde’s Importance of Being Earnest captures the vision I grew up with.

We see Cecily’s governess venturing into literary theory following a confession she makes to her pupil that she once wrote a three-volume novel. An impressed Cecily opines, “I hope it did not end happily? I don’t like novels that end happily. They depress me so much.” To which Prism replies,

The good ended happily, and the bad unhappily. That is what Fiction means.

Wilde’s satiric point is that when we turn fiction into didactic moral lessons–which many of those who ban books want–we get a distorted view of life.

It was such shallow didacticism that Thomas Hardy challenged in his novels, including one in which his “pure woman”—as he provocatively subtitled Tess of the d’Urbervilles—is hanged at the end. I think of what Fielding says at one point in Tom Jones:

There are a set of religious, or rather moral writers, who teach that virtue is the certain road to happiness, and vice to misery, in this world. A very wholesome and comfortable doctrine, and to which we have but one objection, namely, that it is not true.

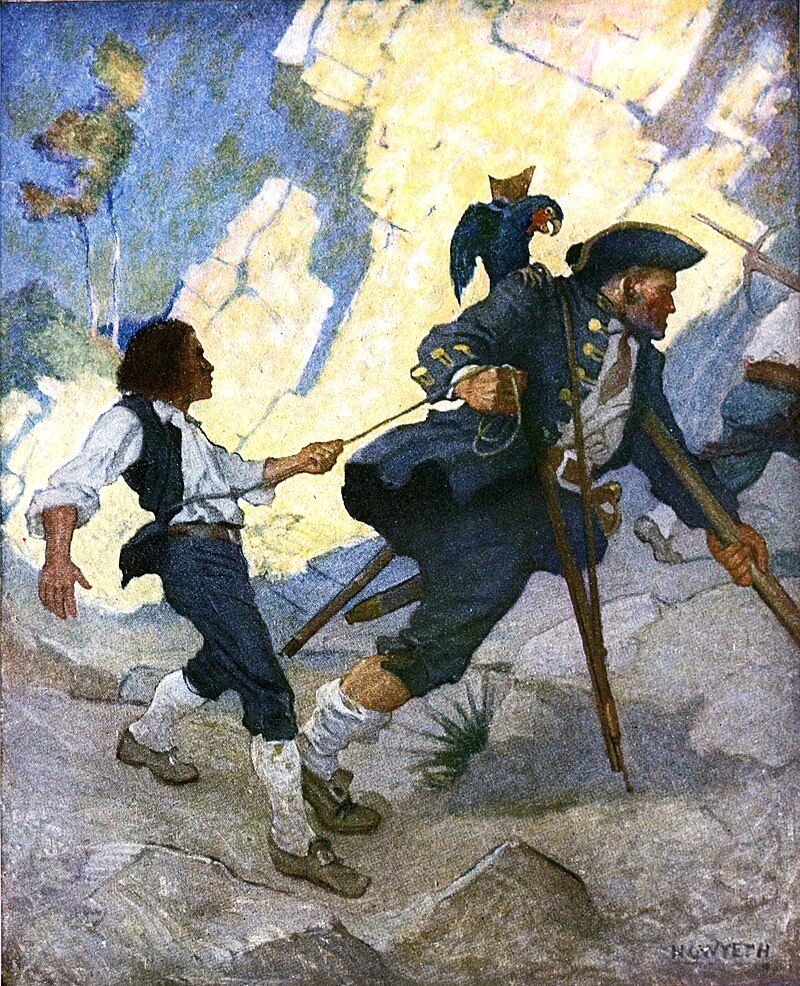

There’s one work that I read as a child that disturbed me by not altogether fitting the formula and that I am now recalling in the wake of Donald Trump’s comeback. Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, one the world’s great adventure tales, involves a grand expedition where Jim Hawkins and his fellow treasure seekers overcome a mutiny and ruthless pirate attacks to attain a treasure. Although their quest is successful, there was one detail that stuck in my throat.

The lead pirate, he who orchestrates the mutiny and who at one point cold-bloodedly breaks a man’s back with his crutch, gets away scot-free.

Long John Silver dominates the book as Donald Trump dominates our political landscape. Throughout the novel he plays a shifting game, in the end double-crossing his own mutineers to curry favor with the winning side. Yet instead of ending up in irons and headed for the gallows, he

was allowed his entire liberty, and in spite of daily rebuffs, seemed to regard himself once more as quite a privileged and friendly dependent. Indeed, it was remarkable how well he bore these slights and with what unwearying politeness he kept on trying to ingratiate himself with all.

And then, he’s gone. The marooned Ben Gunn—he who has led the treasure seekers to the treasure—is still so terrified of Silver that he helps him escape. Think of him as Mitch McConnell, who helped Trump do his own escaping when the Senate was prepared to bar him from ever seeking public office again:

Ben Gunn was on deck alone, and as soon as we came on board he began, with wonderful contortions, to make us a confession. Silver was gone. The maroon had connived at his escape in a shore boat some hours ago, and he now assured us he had only done so to preserve our lives, which would certainly have been forfeit if “that man with the one leg had stayed aboard.” But this was not all. The sea-cook had not gone empty-handed. He had cut through a bulkhead unobserved and had removed one of the sacks of coin, worth perhaps three or four hundred guineas, to help him on his further wanderings.

I think we were all pleased to be so cheaply quit of him.

As a child it bothered me that Silver wasn’t held to account, and I have been similarly shocked at how Trump too gets away with crime after crime. But I understand the relief of everyone on board the ship. After all, this was a man prepared to murder anyone who got in his way.

There’s much discussion about how much damage Trump can do as president, with worst case scenarios involving tearing apart financial regulations, thereby plunging us into another great depression; savaging the environment and hastening climate change; imprisoning millions of immigrants and tearing apart families; implementing a nationwide ban on abortion; and so on.

But above all, Trump wants to turn the presidency into a money-making operation, even more so than before when he was charging the Secret Service exorbitant rates to stay at his golf resorts and taking bribes from autocrats around the world. Large companies are already lining up to give him money and he’s not even president yet. If he discovers that people with money don’t have the same agendas as the ideologues who crafted Project 2025–and sometimes they don’t–then we know which way Trump will go. He won’t hesitate to double-cross former allies it’s to his advantage.

In other words, the lesson I learned from Stevenson’s novel may be a good one: sometimes there are worse things than a bad guy getting away with his crime. If Trump chooses to abscond with 400 guineas rather than kill everyone on board ship, then we have gotten off cheap.