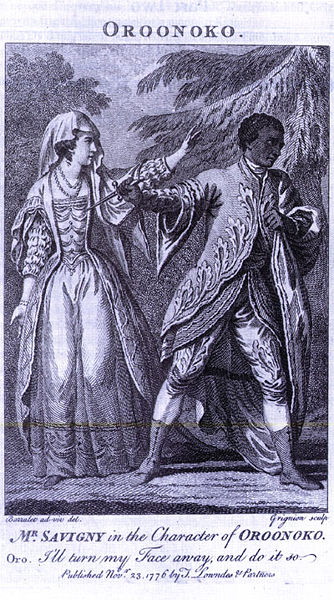

Notice of a theatrical version of Oroonoko

If race has been the subject of these past two weeks of posting it is because, as a Sherrilyn Ifil article notes in the on-line publication Root, we are having a hard time talking about race this summer, what with the furor over the Sonia Sotomayor nomination and the Henry Louis Gates affair. I haven’t heard charges of racism flung around so freely for quite some time, and never before from the right. They’ve even dropped the word “reverse.” I suspect distress over having an African American for a president is behind the “Birther” movement (those who claim that President Obama was born in Kenya) and that it factors into some of the raucous town hall health care meetings. (Other factors would be the bad economy and high anxiety over the way the government has been stepping up to address our various crises). Anyone who thinks we entered a post-racial society when we elected Obama must be rethinking that hope by now.

Yesterday I talked about how one of the shortcomings of Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird—and probably of Harper Lee as well—is that he sees race as a personal rather than an institutional problem. He does what he can in his own sphere but he doesn’t challenge the system as a whole. I’d like to elaborate on that idea here, turning for help to a seventeenth-century slave narrative.

Aphra Behn wrote Oroonoko or The Royal Slave: A True History in 1688. Behn was an extraordinary woman, one of the first to make her living by her pen, and Oroonoko is the work for which she is best remembered. It is supposedly the account of a friendship that she had with a royal African slave when she was young and living in the British colony of Surinam (later Dutch Surinam). We don’t know how much of the history is accurate—Behn may have made most of it up—but she could well have befriended an African slave. She describes Oroonoko as a remarkable man and talks about how, after being tricked aboard a slave ship, he arrives at Surinam, where he discovers his long-long mistress (also a slave), leads a slave rebellion, and is savagely tortured and killed by the British.

I return to this book time and again because I find it such a rich exploration of (among other things) the intricacies of friendship across race, class, and gender lines. I talk about it today because of the way that Behn finds her personal relationship with Oroonoko constantly compromised by their power discrepancy. This is not an issue that Harper Lee addresses.

Here’s an example. The English colonists recognize what a great man Oroonoko is and give him more freedom than the other slaves. He spends a lot of time talking with Behn, who keeps on reassuring him that he will be freed once the new lieutenant governor arrives on the island. After a while, however, he becomes suspicious of her reassurances. When he discovers that Imoinda/Clemene, his wife, is pregnant and that his child risks being born into slavery, he becomes more urgent.

The complicated nature of the Behn-Oroonoko friendship is captured in the following passage:

I had opportunity to take notice of him that he was not well pleased of late as he used to be, was more retired and thoughtful; and told him I took it ill he should suspect we would break our words with him and not permit both him and Clemene to return to his own kingdom, which is not so long a way but when he was once on his voyage he would quickly arrive there. He made me some answers that showed a doubt in him which made me ask him what advantage it would be to doubt. It would but give us a fear of him, and possibly compel us to treat him so as I should be very loath to behold; that is, it might occasion his confinement. Perhaps this was not so luckily spoke of me, for I perceived he resented that word which I strove to soften agin in vain. However, he assure me that whatsoever resolutions he should take, he would act nothing upon the white people; and as for myself and those upon that plantation where he was, he would sooner forfeit his eternal liberty, and life itself, than lift his hand against his greatest enemy on that place…

Before I parted that day with him, I got, with much ado, a promise from him to rest yet a little longer with patience, and wait the coming of the Lord Governor, who was every day expected ton our shore; he assure me he would, and this promise he desired me to know was given perfectly in complaisance to me, in whom he had an entire confidence.

After this, I neither thought it convenient to trust him much out of our view…

What strikes me about this conversation is how tangled it gets (not an usual quality in conversations about race). Behn warns Oroonoko that, if he continues to be discontented, the English might have to lock him up. She then realizes that she has just issued a threat and tries to soften it. He, meanwhile, perhaps realizing he has revealed too much to someone who looks like his enemy (to paraphrase Lucille Clifton), tries to pull back and soften things as well. Each desperately wants the friendship of the other, but true friends would not have to engage in these circuitous games.

The lack of complete trust, however, is not their fault. Their friendship is coming up against the system that makes her free and him a slave. Regardless of their good intentions, the system ultimately carries the day. By the end of the book, Behn has nothing but memories of what, in spite of its limitations, may have been the greatest friendship of her life, along with her guilt at having been part of the system which destroyed Oroonoko.

And that is why we must continue to talk about and work against race inequality (and sex inequality and class inequality), even when we are the beneficiaries of the disparity. Inequality robs us of possible friendships that would enrich our lives immeasurably. When power disparities cut us off from other people, we are impoverished in ways that far outweigh any material benefits.

Behn doesn’t put it this way because she can’t imagine a world without slavery. As she sees it, that’s just how things are. But she knows that something is contaminating a friendship that is precious, and she describes the consequences in a gripping story. We, who are much closer to a post-racial society (even if we’re not there yet), can use her book to remind ourselves why we must keep addressing issues of racial inequality, as uncomfortable as they may be for us.