Tuesday

When Hurricane Harvey hit the Texas and Louisiana coasts, Joel Osteen, a prosperity televangelist who refused to offer his megachurch to storm victims, came in for fierce criticism. He eventually capitulated, but his lack of immediate sympathy points to prosperity theology’s inability to adequately address the problem of human suffering. If you preach that one’s fate is tied to one’s faith, then how do you account for a storm that ravages believers and nonbelievers alike?

I found myself wishing that Leo Tolstoy had gotten a shot at Osteen. In his final novel Resurrection, the author shows what he thinks of those who equate the love of Christ with the love of mammon.

Osteen preaches “prosperity theology,” which a recent Newsweek article defines as

the theological equivalent to the American Dream. The essence of the prosperity gospel is simple: Faith brings rewards, not only in the afterlife—as taught in all mainstream forms of Christianity—but also in the earthly life. These rewards can take the form of health, career success, and, most controversially, wealth.

Newsweek’s Conor Gaffey reports that the most noteworthy adherent of the prosperity gospel is Donald Trump:

The Trump family attended Marble Collegiate Church in New York City, where the pastor was Norman Vincent Peale, author of The Power of Positive Thinking, a 1952 book that sold millions and was translated into more than a dozen languages. Trump has cited Peale as a mentor, telling the Iowa Family Leadership Summit in 2015 that he could listen to Peale “all day long. And when you left the church, you were disappointed it was over. He was the greatest guy.”

This may help explain some of Trump’s otherwise baffling support from certain evangelicals. Gaffey reports how prosperity preachers are amongst Trump’s close advisers:

The presidential board of evangelical advisers, convened by Trump in 2016 to help him (successfully) court the religious right vote, also comprises of several high-profile prosperity preachers. Trump’s closest spiritual adviser, Paula White, the pastor of a Florida megachurch and popular Christian commentator, is one. White told an audience at a 2007 event: “Anyone who tells you to deny yourself is from Satan.”

Kenneth Copeland, another Texas televangelist, teaches that “financial prosperity is God’s will for you” and that believers should pray for financial provision from God. (Osteen is not on the board and never officially endorsed Trump’s presidential bid, though he did describe Trump as a “friend of our ministry” and “a good man.”)

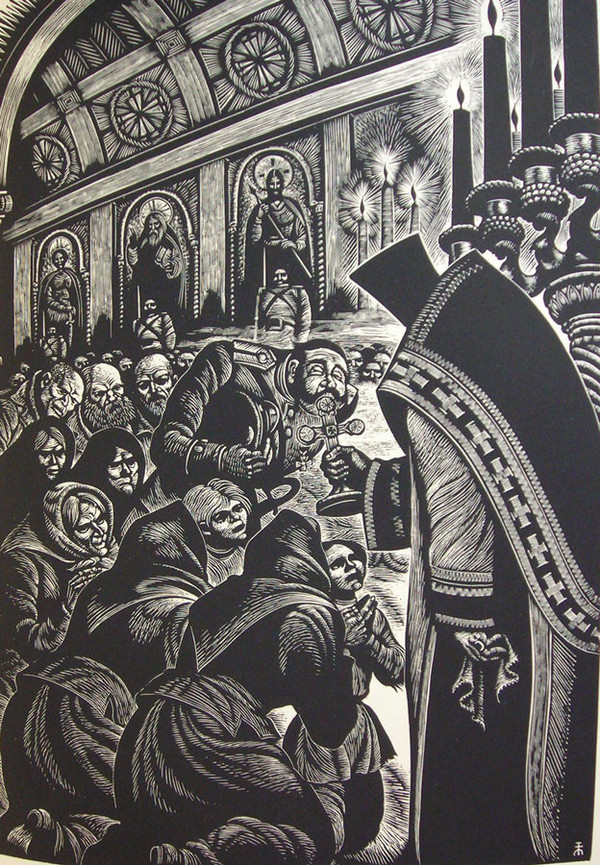

While Tolstoy goes after the Russian Orthodox Church rather than a Protestant spinoff, his critique of those who profit from religion still applies. After straightforwardly describing a church service for mistreated Russian prisoners, the novelist unloads:

And none of those present, from the inspector down to Maslova, seemed conscious of the fact that this Jesus, whose name the priest repeated such a great number of times, and whom he praised with all these curious expressions, had forbidden the very things that were being done there; that He had prohibited not only this meaningless much-speaking and the blasphemous incantation over the bread and wine, but had also, in the clearest words, forbidden men to call other men their master, and to pray in temples; and had ordered that everyone should pray in solitude, had forbidden to erect temples, saying that He had come to destroy them, and that one should worship, not in a temple, but in spirit and in truth; and, above all, that He had forbidden not only to judge, to imprison, to torment, to execute men, as was being done here, but had prohibited any kind of violence, saying that He had come to give freedom to the captives.

No one present seemed conscious that all that was going on here was the greatest blasphemy and a supreme mockery of that same Christ in whose name it was being done. No one seemed to realize that the gilt cross with the enamel medallions at the ends, which the priest held out to the people to be kissed, was nothing but the emblem of that gallows on which Christ had been executed for denouncing just what was going on here. That these priests, who imagined they were eating and drinking the body and blood of Christ in the form of bread and wine, did in reality eat and drink His flesh and His blood, but not as wine and bits of bread, but by ensnaring “these little ones” with whom He identified Himself, by depriving them of the greatest blessings and submitting them to most cruel torments, and by hiding from men the tidings of great joy which He had brought. That thought did not enter into the mind of any one present.

Tolstoy then lays out what the various parties gain from religious practice:

The priest did his part with a quiet conscience, because he was brought up from childhood to consider that the only true faith was the faith which had been held by all the holy men of olden times and was still held by the Church, and demanded by the State authorities. He did not believe that the bread turned into flesh, that it was useful for the soul to repeat so many words, or that he had actually swallowed a bit of God. No one could believe this, but he believed that one ought to hold this faith. What strengthened him most in this faith was the fact that, for fulfilling the demands of this faith, he had for the last 15 years been able to draw an income, which enabled him to keep his family, send his son to a gymnasium and his daughter to a school for the daughters of the clergy. The deacon believed in the same manner, and even more firmly than the priest, for he had forgotten the substance of the dogmas of this faith, and knew only that the prayers for the dead, the masses, with and without the acathistus, all had a definite price, which real Christians readily paid, and, therefore, he called out his “have mercy, have mercy,” very willingly, and read and said what was appointed, with the same quiet certainty of its being necessary to do so with which other men sell faggots, flour, or potatoes. The prison inspector and the warders, though they had never understood or gone into the meaning of these dogmas and of all that went on in church, believed that they must believe, because the higher authorities and the Tsar himself believed in it. Besides, though faintly (and themselves unable to explain why), they felt that this faith defended their cruel occupations. If this faith did not exist it would have been more difficult, perhaps impossible, for them to use all their powers to torment people, as they were now doing, with a quiet conscience. The inspector was such a kind-hearted man that he could not have lived as he was now living unsupported by his faith. Therefore, he stood motionless, bowed and crossed himself zealously, tried to feel touched when the song about the cherubims was being sung, and when the children received communion he lifted one of them, and held him up to the priest with his own hands.

In Flight Behavior, which I’ve just finished teaching, Barbara Kingsolver’s protagonist sees the church as “a complicated pyramid scheme of moral debt and credit resting ultimately on the shoulders of the Lord, but rife with middle managers.” Osteen’s and Trump’s pyramid schemes are not just metaphysical. Actual money changes hands.

For further reading:

A powerful early exposé of prosperity theology is Howard Nemerov’s poem “Boom” (1957). Check it out in my post, “When Christianity Becomes a Money Cult.”