Friday

At the end of each year I look over the past year’s posts and choose one that I find particularly important. This year I found three that stand out to me, all dealing (of course) with the most significant news story of the year.

I won’t repost my favorite since I’ve already reposted it once. It was about how Donald Trump galvanizing the KKK, neo-Nazis, and other members of the so-called alt-right is like Satan inspiring Sin and Death in Paradise Lost. The two demons intuitively sense when Satan has succeeded in Eden and immediately pave a road over chaos so that all the devils can invade Earth. As I wrote at the time, “whatever happens in November, Trump has opened the gates of hell, and we will be dealing with the consequences for years to come.”

I’ve chosen to print both of the other two posts. The first uses Raymond Carver’s short story “Why, Honey?” to explore the GOP’s complicity in Trump’s rise. The second looks at Herman Melville’s Confidence-Man to better understand how Trump has pulled off his con. The second uses the:

Raymond Carver and Trump’s Enablers

Reprinted from Feb. 24, 2016

Yesterday Ruth Arseneault, a teacher who occasionally comments on this blog, tweeted, “Terrified of Trump? Read Raymond Carver’s story ‘Why, Honey?’” So I did and now Trump has become even more nightmarish to me than he already was. Thank you very much, Ruth.

“Why, Honey” is a letter written by a mother responding to a stranger’s letter asking her about her son, now a governor and celebrity.(You can read the short story here.) We know something bad has happened because she reveals that she is currently hiding from him:

I was so surprised to receive your letter asking about my son, how did you know I was here? I moved here years ago right after it started to happen. No one knows who I am here but I’m afraid all the same. Who I’m afraid of is him. When I look at the paper I shake my head and wonder. I read what they write about him and I ask myself is that man really my son, is he really doing these things?

The paranoia proves to be justified. The mother recounts various disturbing incidents, including blowing up the family cat, possibly robbing stores, and maybe even killing someone (although that’s not entirely clear). Veering between denial and enabling, she finally loses touch with him when he becomes, in an unexpected development, a politician.

The letter concludes with a deep sense of dread:

I began to see his name in the paper. I found out his address and wrote to him, I wrote a letter every few months, there never was an answer. He ran for Governor and was elected, and was famous now. That’s when I began to worry.

I built up all these fears. I became afraid. I stopped writing to him, of course, and then I hoped he would think I was dead. I moved here. I had them give me an unlisted number. And then I had to change my name. If you are a powerful man and want to find somebody, you can find them, it wouldn’t be that hard.

I should be so proud but I am afraid. Last week I saw a car on the street with a man inside I know was watching me, I came straight back and locked the door. A few days ago the phone rang and rang, I was lying down. I picked up the receiver but there was nothing there.

The dread experienced by the mother merges with my own growing dread as I contemplate the prospect of a Trump presidency. As Ezra Klein of Vox observes, this is a man who seems impervious to shame and so would not be reined in by the normal internal checks that govern political behavior. (Klein’s video explanation at the conclusion of this article is worth watching.) What would such a man be capable of if he had the power of the presidency behind him? Given the vindictive joy with which he takes down his Republican rivals, would he be another Nixon? Mainstream conservatives are already imagining an enemy’s list.

One chilling scene in particular seems to capture Trump’s determination to humiliate others, especially Jeb Bush. When her son is about to graduate from high school, for the first time in her life the mother confronts him about his lifetime of lies. Why do you do it, she asks. Here’s his response:

He didn’t say anything, he kept staring, then he moved over alongside me and said I’ll show you. Kneel, is what I say, kneel down is what I say, he said, that’s the first reason why.

The story applies just as much to the party that enabled Trump as it does to Trump himself. Like the mother in the story, for the longest while the GOP found ways to overlook or excuse Trump’s behavior. They didn’t call him out for his birther attacks against the president or even his depiction of Mexican immigrants as rapists and murders. To be sure, they are outraged now, but it’s a bit late in the game for that. After all, he has left his mother’s house and is on his own.

His supporters, meanwhile, are sitting in a car across the street taking notes. Occasionally they make phone calls.

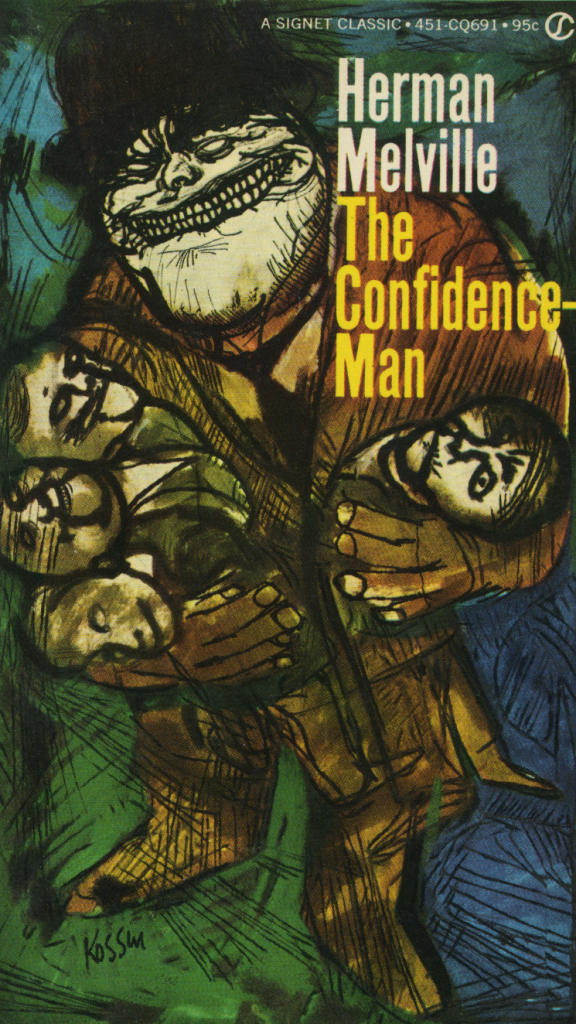

Trump as Melville’s Confidence Man

Reprinted from August 15, 2016

One of the most memorable lines for me from the National Democratic Convention was New York billionaire Michael Bloomberg saying about Donald Trump, “I am from New York and I know a con when I see one.” Since then, I’ve been reading Herman Melville’s The Confidence Man to see if it will give me insights into the nature of Trump’s con.

I’ll be turning to the novel a number of times during this election season, but let me start with this. Melville helps explain why, as Nicholas Kristof of The New York Times puts it, “One persistent narrative in American politics is that Hillary Clinton is a slippery, compulsive liar while Donald Trump is a gutsy truth-teller.” In a recent NBC poll, only 11% of voters chose to describe Clinton as “honest and trustworthy” (as opposed to 16% for Trump).

Even the idea that Clinton and Trump are in the same category Kristof finds to be preposterous. “If deception were a sport,” he writes, “Trump would be the Olympic gold medalist; Clinton would be an honorable mention at her local Y.”

A study by Politifact of presidential candidates since 2007 bears Kristof out. Clinton is second only to Obama in truthfulness, finishing ahead of Jeb Bush and Bernie Sanders. Trump, on the other hand, leads everyone in lying, even Michele Bachman and Ted Cruz. One of the characters in The Confidence Man explains why we may find ourselves surprised by Hillary’s high rating.

Melville’s novel is about a flimflam artist who boards a steamboat and dons a series of disguises to bamboozle the passengers. At one point he goes to work on the ship’s barber, who has put a “No Trust” sign—meaning no credit—in his window. The confidence man convinces him to start trusting people, after which he wriggles out of paying for his shave.

The barber helps us understand how Trump makes his lies compelling, even getting at the way the Trump’s flamboyant hair gives him confidence. (The barber also gets at Trump’s underlying insecurity–without such hair, the barber says, a man is shamefaced and fearful.) We also learn why Clinton’s careful word choices damage her as much as Trump’s “pants on fire” “four Pinocchios” fabrications. Responding to the question, “how does the mere handling of the outside of men’s heads lead you to distrust the inside of their hearts?”, the barber replies,

[C]an one be forever dealing in macassar oil, hair dyes, cosmetics, false moustaches, wigs, and toupees, and still believe that men are wholly what they look to be? What think you, sir, are a thoughtful barber’s reflections, when, behind a careful curtain, he shaves the thin, dead stubble off a head, and then dismisses it to the world, radiant in curling auburn? To contrast the shamefaced air behind the curtain, the fearful looking forward to being possibly discovered there by a prying acquaintance, with the cheerful assurance and challenging pride with which the same man steps cheerful assurance and challenging pride with which the same man steps forth again, a gay deception, into the street, while some honest, shock-headed fellow humbly gives him the wall!

And then the passage that explains Clinton’s problem:

Ah, sir, they may talk of the courage of truth, but my trade teaches me that truth sometimes is sheepish. Lies, lies, sir, brave lies are the lions!”

So there you have it: Trump tells brave lies whereas Hillary engages in sheepish equivocations.

The follow-up passage has relevance to the Trump campaign as well. When the confidence man accuses the barber of participating in a fraud, the man replies, “”Ah, sir, I must live.”

This sounds very much like the ghostwriter who wrote Trump’s The Art of the Deal and now, according to Jane Mayer’s remarkable New Yorker article, is wracked with guilt. Like the barber, he says that he did it because he had bills to pay:

Around the time Trump made his offer, [Tony] Schwartz’s wife, Deborah Pines, became pregnant with their second daughter, and he worried that the family wouldn’t fit into their Manhattan apartment, whose mortgage was already too high. “I was overly worried about money,” Schwartz said. “I thought money would keep me safe and secure—or that was my rationalization.”

What happens when we dance with a professional confidence man? We get conned. Why are we surprised?