Wednesday – Anniversary of 9-11

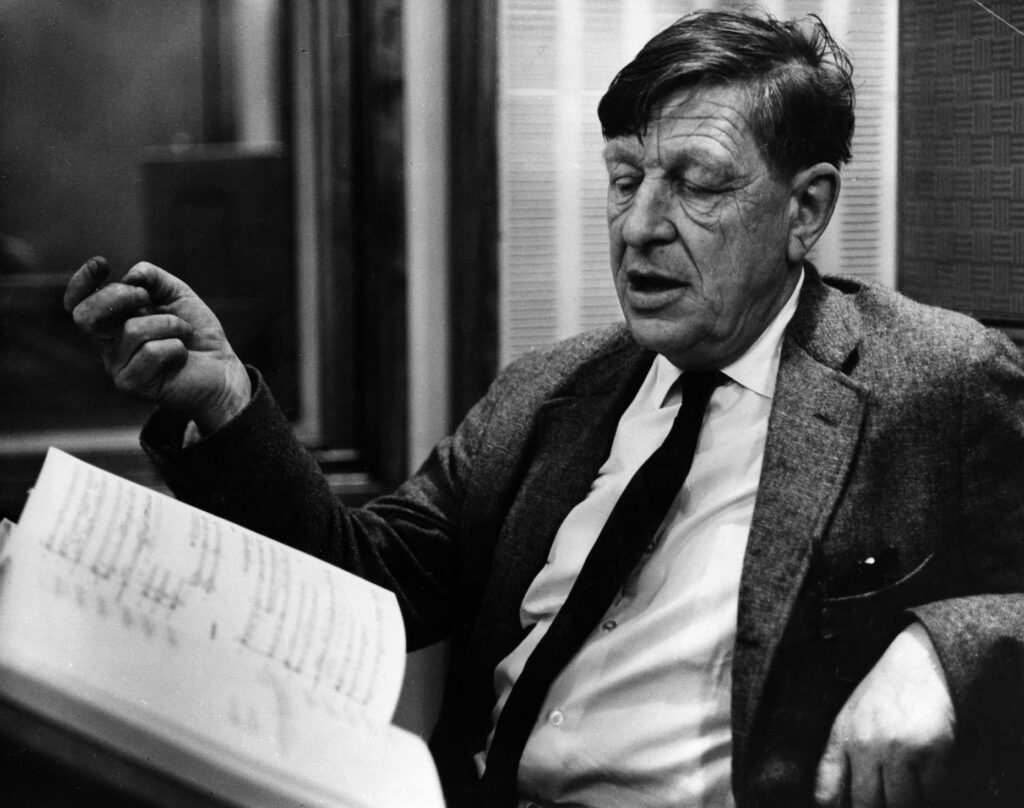

I recently came across an article that references W.H. Auden’s “September 1, 1939,” which reminded me that many people turned to it 23 years ago on this day. Auden was writing about something even more momentous, the day that Hitler set off World War II with his invasion of Poland, and the poet floundering as he grasps for hope is one thing that made the poem seem so timely 62 years later. Revisiting how it resurfaced in 2001 is one way of recalling what Americans were feeling after the Twin Towers and the Pentagon were attacked.

First, however, let me explain the recent reference. Tufts history professor David Ekbladh uses Auden’s phrase “low dishonest decade” to make the point that our situation in 2024 may be closer to Auden’s than we think. Just as authoritarianism was on the rise in the 1930s, so we today are also seeing assaults on democratic rule. “To a critical eye,” Edbladh writes, “the world [today] looks less like the structured competition of that Cold War and more like the grinding collapse of world order that took place during the 1930s.” He fears that we too may be heading towards liberal democracy’s demise.

On this happy note, I turn to what people experienced on that September day on 2001. To capture his own feelings, Scott Simon of National Public Radio read for his audience the following excerpts from Auden’s poem:

I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-second Street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low dishonest decade:

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth,

Obsessing our private lives;

The unmentionable odor of death

Offends the September night.

…

Faces along the bar

Cling to their average day:

The lights must never go out,

The music must always play,

All the conventions conspire

To make this fort assume

The furniture of home;

Lest we should see where we are,

Lost in a haunted wood,

Children afraid of the night

Who have never been happy or good.

For the error bred in the bone

Of each woman and each man

Craves what it cannot have,

Not universal love

But to be loved alone.

…

All I have is a voice

To undo the folded lie,

The romantic lie in the brain

Of the sensual man-in-the-street

And the lie of Authority

Whose buildings grope the sky:

There is no such thing as the State

And no one exists alone;

Hunger allows no choice

To the citizen or the police;

We must love one another or die.

Defenseless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet, dotted everywhere,

Ironic points of light

Flash out wherever the Just

Exchange their messages:

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and of dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair,

Show an affirming flame.

Poet Eric McHenry, writing about the poem nine days later in Slate, noted that poetry is meant for occasions like this. When we get “nothing but cant from public figures and TV personalities,” he pointed out, “people crave language that’s as precise as their pain.”

Simon quotes the parts of the poem that are the most immediately applicable, leaving out some of the history that Auden invokes. This includes the following passage, which is a reference to the Greek historian who recorded the the catastrophic rise of those demagogues that contributed to the end of Athens’ democratic experiment:

Exiled Thucydides knew

All that a speech can say

About Democracy,

And what dictators do,

The elderly rubbish they talk

To an apathetic grave;

Analysed all in his book,

The enlightenment driven away,

The habit-forming pain,

Mismanagement and grief:

We must suffer them all again.

Having just finished watching Trump debating Kamala Harris, I have to say that “elderly rubbish” sounds about right for dictators (or at least this wannabe dictator). And “habit-forming pain” is another way of capturing how we’ve managed to normalize him, the way that an abused women normalizes her husband’s violence.

Another passage that catches McHenry’s attention is Auden’s reference to “blind skyscrapers” that “use their full height to proclaim/ The strength of Collective Man.” To the hijackers, the Twin Towers seemed to signal America flexing its muscles before the world, which is one reason why they chose them. In bringing them down, therefore, they managed to undermine Americans’ easy self-confidence—just as, in recent years, Trump has undermined our easy confidence that the guardrails of our democracy would ultimately save us:

Into this neutral air

Where blind skyscrapers use

Their full height to proclaim

The strength of Collective Man,

Each language pours its vain

Competitive excuse:

But who can live for long

In an euphoric dream.

Out of the mirror they stare,

Imperialism’s face

And the international wrong.

In the face of Hitler’s invasion, Auden resolves to “show an affirming flame.” Following 9-11, America too came together (although, granted, not with positive results as George W. Bush used our euphoria over new-found unity to steer us into an insane and unjust war). Today, we can once again refuse to surrender to “negation and despair.” Looking back over last night’s presidential debate, where Harris was clearly on the offense while Trump was in a defensive crouch, there’s hope that (to use one of her expressions) we might finally be turning the page on Trumpism.

Further thought: Auden later disavowed the poem and refused for the longest time to allow anthologies to include it. For instance, in retrospect he thought the line “We must love one another or die”–which he coined when he was desperately looking for solace–was hopelessly naive. After all, we are going to die anyway. But in the poem’s defense, there are different ways of dying and one is forgetting that love is still an option even in the most perilous of times. McHenry makes the good point that Auden is frustrated that language, even the language of poetry, couldn’t do justice to the moment and so turned his back on this attempt.

The frustation is common amongst great poets. As Shakespeare as Theseus say in Midsummer Night’s Dream (he’s being generous about the wretched play the wedding party is watching) that even “the best of this kind are but shadows.” And if Shakespeare, who did in fact write “the best of this kind,” is dissatisfied, what help for the rest of us. But his point is that no artistic creation can live up to vision a poet has in his or her mind. What’s important is that Auden’s poem brought deep comfort to us at a time when we needed deep comfort. At that moment, his dissatisfaction with it was irrelevant.