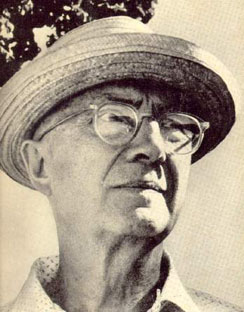

Poet William Carlos Williams

Today I want to thank Chris Kalb, whose artwork on this blog was installed yesterday. And also to thank Discovering Oz, my son and his wife’s marketing company, which gave me the idea for setting up this website and blog and then helped me carry it out. In the illustration you see before you, the stacks of books (all from my library) are meant to capture the way that I have felt enveloped in books from early childhood. The illustrations, meanwhile, speak to literature’s imaginative play. Poetry, as Homer, Pindar, Horace and Swift have all noted, is both sweetness and light, both fun and instructive. Over the ages the bee has often been seen as a symbol of the author, generating both honey (sweetness) and candle wax (light). Literature is airy nothing and literature is great import. Chris’s illustration and Darien and Betsy’s layout are designed to capture this paradox.

To mark the occasion, I will address a fundamental question about literature, namely, what good is it. I was reminded that many Americans wonder about this when I read the following question in the Personality section of this past Sunday’s Parade Magazine. Editor Walter Scott provides a wonderful quotation in his response:

Q: Why are my tax dollars going to pay a poet laureate when nobody reads poetry?

Jeff Kawabata, Omaha, Neb.

A: “It is difficult/to get the news from poems/yet men die miserably every day/for lack/of what is found there,” wrote the great American poet William Carlos Williams. (We hope you’ll look him up!) While it’s true that not many people read poetry, they’d probably get a lot out of it if they gave it a try. The current U.S. Poet Laureate, Californian Kay Ryan, earns all of $35,000. But fret not: Her stipend is funded from a private endowment, not tax revenues.”

America’s suspicion of the arts, which traces back to the early days of our republic, could not be put more bluntly. Think of it as American pragmatism taken to the extreme. And if life were about no more than food in our bellies, shelter over our heads, protection from our enemies, and a mate to procreate with, then it might be hard to make a case for poetry’s unpractical use of words.

But human beings are creatures with imaginations as well as bodies. We hunger for things of the spirit as well as things of the earth, and poetry opens windows into that world. Has Mr. Kawabata never had his heart stirred by a song lyric or been lifted by a rhetorical flourish in a speech? Has he never heard poetry read at a graduation ceremony or a wedding or a funeral service? For that matter, has he never had his mind taken over by punchy advertising slogans, the most memorable of which use poetic devices like alliteration, assonance, rhythm, rhyme, and imagery?

Williams claims that people die miserably every day for lack of what is found in poetry. (Here is an excerpt of the poem in which the lines appear.) Is this true? Well, Williams was a doctor as well as a poet so I suspect he saw more people die than most of us do. (He is also credited with having delivered close to 2,000 babies in his lifetime.) Maybe he’s talking about metaphorical death, a depressed state that allows no room for imaginative play or light or music or dancing. But then again, maybe he’s talking about people who are actually dying. Maybe he has seen patients who, after a life of down-to-earth pragmatism, found themselves staring into the abyss and asking whether they had missed something along the way.

Along these lines, I am struck by how, in funerals, people often choose the rich cadences of the King James Version of the Bible over more matter-of-fact modern translations. The King James Bible was translated in the age of Shakespeare by men who wrote with an ear for poetry (including a fondness for archaisms). “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.” This is not language that merely delivers the news.

Rather than continuing with my defense of poetry, however, I want to return again to Mr. Kawabata. Because I suspect that, when he says no one is reading poetry, he is talking about a certain caricature of poetry. Maybe he has an image of people talking in a language that he can’t understand, of pretentious snobs who elevate themselves above him and look down on him. And they’re probably liberal besides. Why should his tax dollars go to them?

If I am reading him right, then poets and the American academy may bear some responsibility. At least that’s the argument of literary scholar Robert Scholes. In a book that I will look at in more depth next week (The Crafty Reader), Scholes argues that intricate and highly allusive poets like T. S. Eliot and the so-called new critics of the 1950’s made so much fun of middle brow poetry (say, Joyce Kilmer’s “I think that I shall never see/A poem as lovely as a tree”) that they drove away a reading public that used to be much more open to poetry. They set themselves up as supreme arbiters of taste but, in their victory, found themselves suddenly alone.

More on this next week when I retrieve the book. I will just note here that one goal of my blog is to break down some of the barriers between literature and everyday reality. I think that literature dies when it is set on a pedestal. I think poems and novels and plays were written to wade into the thick of what concerns us most, giving us perspective on our issues and helping us work through them. Beowulf was not composed for effete audiences, nor was Hamlet. Every week, Monday through Friday, I will provide examples of literature mixing it up with life. Thank you for joining me.

One Trackback

[…] Kawabata’s query led editor Walter Scott to quote the Williams lines in response. Last August I wrote about the interchange here. […]