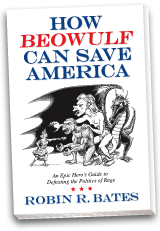

An Epic Hero’s Guide to Defeating the Politics of Rage

Imagine a society …

seething with resentment because of the perception that certain groups receive special treatment …

beset by grief about the decline of its glory days …

grown hard and callous, with miserly leaders unwilling to redistribute the country’s wealth.

Sound familiar?

This is the world of 9th Century England, where a society facing the constant threat of decimation finds guidance in the great English epic Beowulf. The poem understands how rage, taking the form of monstrous resentment, vengeful grieving, and venomous greed, can tear a society apart.

The monsters in Beowulf are no less present in America today, taking up habitation in the extreme right, their enablers in the political class, and the cynical and self-absorbed 1%. By examining the poem’s namesake, and his monster-fighting tactics, literature professor Robin Bates shows how the poem provides a blueprint for combating the great challenges facing America today and for reclaiming the promise of a society that insures justice, equality, and the promise of a good life for all.

FROM THE BOOK:

To defeat the politics of rage, we must go to the root of the problem. In the first two monsters that Beowulf battles, a troll and his mother, we can see the resentment and the angry grieving that are tearing our country apart. But it is the third monster, the dragon, that reveals our underlying malaise. In Anglo-Saxon times, society had a dragon problem when it experienced discrepancies in wealth that its people perceived as grossly unfair. Greedy kings were regarded as dragons whose hoarding undermined the society’s sense of unity. In America today, middle-class income stagnation and a growing gap between the middle class and the very wealthy have led to dissension such as we have not seen since the early days of the Great Depression.

Addressing the causes of this monstrous anger will not only restore a semblance of political peace to our beleaguered nation. It will also allow us to look once again toward the future. In the poem, Beowulf’s victory over the dragon liberates a cave filled with immense riches. If wealth were once again to flow freely through America, we could rebuild a country that answers to our needs and dreams.

How do we size up our monsters and figure out a battle plan? Beowulf leads the way.

The Country under Siege

As we look back to the early days of Barack Obama’s presidency, we might well conclude that the president brought the wrong weapons to the fight. In 2008 he believed, along with many Americans, that simple outreach could lead the country past its bitter partisan divides and into a new era of cooperation. “There is not a liberal America and a conservative America—,” he declared in his acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention, “there is the United States of America.” In Obama’s vision, people would reach beyond their antagonisms to find a common purpose. It would take work, of course—as a former community organizer and U.S. senator, Obama knew that people are often driven by self-interest—but he thought that most of us would realize that collaboration benefited everyone. His job, as he saw it, was to get everyone to the table where they could engage in bipartisan negotiating.

We now know that events didn’t unfold as the president had hoped. Instead of witnessing a new spirit, America saw its polit- ical divides grow yet more toxic. Angry trolls rampaged through America’s mead hall, and the brave young warrior who was supposed to clean up the mess became a discouraged king presiding over it.

Obama should have read Beowulf.

If he had, he would have seen the anger directed against him in all of its destructive intransigence. Literature, Shakespeare mem- orably writes, holds a mirror up to nature, and Beowulf is particularly adept at mirroring rage. The epic’s genius lies in the way it grasps the essence of destructive anger, distilling it into unforgettable figures. Mere human characters wouldn’t capture the insanity half as well as Beowulf’s nightmarish creatures.

The poem also understands how anger strips us of our humanity and turns us into monsters. Through vivid depictions of Grendel, Grendel’s Mother, and the dragon, Americans can see what we are up against. We learn, for instance, that anger takes at least three different forms, each with its own characteristic mode of attack and each posing a distinctive threat to society. We also learn that each manifestation of anger must be fought in a particular way.

The poem understands anger because it was written during a time that was intimately acquainted with violence. Anglo-Saxon society regularly witnessed skirmishes between neighboring kingdoms, not to mention battles against invading Vikings. If hostile warriors overran a village, all its citizens could be killed or enslaved. The society experienced internal instances of violence as well, often in the form of interminable blood feuds. Fighting could also break out after the death of a king, with different rel- atives and warriors vying to succeed him.

In America today we do not face threats of death and enslavement. We do, however, face a roiling anger that is undermining our governing institutions, setting citizen against citizen, and preventing collective problem-solving. In its account of Beowulf battling and defeating the three monsters, the epic captures our own situation and shows us how to deal with it.

America’s Monsters

The first monster, Grendel, represents angry resentment. Grendel is a giant troll who is driven mad by the merriment of others. Excluded as he is from the great mead hall where King Hrothgar distributes the society’s wealth, he writhes in envy. Significantly, he doesn’t touch the king’s throne when he invades the hall, which is to say he doesn’t vent his anger against the wealth-distributing system. He directs it rather towards the beneficiaries of the king’s largesse, the king’s warriors, whom he butchers and devours in a blind rage.

We see a comparable rage in those American citizens who verbally lash out at neighbors who they think have been unfairly granted privileges. Over the past three years, such resentful rage has been directed against, among others, undocumented workers, American Muslims, African Americans, Latinos and Latinas, teachers, government workers, union members, delinquent homeowners, Planned Parenthood clients, and food stamp recipients. Every day, it seems, new groups are added to the list. When it comes to certain scapegoats in America today, otherwise decent people harden over and say ugly things. Grendelian resentment thus has the power to rend the social fabric.

Beowulf’s second monster alerts us to the fact that angry resentment doesn’t travel alone. It is accompanied—indeed, it has been birthed—by grief. Although Beowulf manages to kill Grendel, retaliation arrives the very next night in the form of Grendel’s vengeful mother. The connection between the two mon- sters leads us to realize that resentment always contains an element of sorrow. Grendel and Grendel’s mother function as an inextricable pair.

Many Americans possessed by Grendel’s resentment also feel that they have lost something close to their hearts. Look closely at the anger directed against fellow citizens and you will usually find at its core a grieving for a lost America. Many extol the virtues of a previous golden age, which in their view can look like idealized versions of 1950s suburbia, the small-government frontier West, the America of the Founding Fathers, and occasionally even the antebellum South. Grendel’s Mother may strike second in the poem, but she precedes resentful rage and lives deep within us.

The poem’s final monster is the dragon, which makes its appearance late in Beowulf’s reign as a successful king. The dragon is the emblem of a culture in which wealth no longer circulates freely and where people have ceased to be generous. Dragons are scaly hard, venomous, angry, and self-absorbed. Dragonhood is particularly debilitating because it represents the triumph of cynicism over idealism. When a society loses hope in its future, people retreat into their lairs, determined to at least protect what they already have.

Beowulf’s portrayal of the dragon invites us to identify and explore despair, which might be our deepest anger. The poem is also a call to explore the greed and the unequal distribution of wealth out of which cynicism and desperation arise. In Anglo- Saxon society, society’s basic social contract called for warriors to be loyal to their kings and for kings to generously redistribute the wealth that warriors brought in. If a king began to hoard instead of share, warrior loyalty was strained, uncertainty entered the pic- ture, and gloom descended.

America has its own version of this basic contract and its own version of dragon greed.