For very understandable reasons, the Sandy Hook massacre has so grabbed our attention that other momentous news developments have gone overlooked. One of these is the anti-union blitzkrieg that recently occurred in Michigan where, in one day, the GOP turned the cradle of the American labor union movement into a “right to work” state. Translate that as a “right to work for less” state.

Whenever I need to understand union matters, I turn to my friend Rachel Kranz, who has written a powerful novel about labor organizing. I’ll share observations from her novel Leaps of Faith in a moment.

The new laws don’t actually ban collective bargaining, as was the case in Wisconsin and Ohio. Rather, as Jonathan Chait explains it, they make it optional for workers in unionized workplaces to pay the agency fees for unions negotiating on their behalf. If unions manage to negotiate better wages, better benefits, or better working conditions, thanks to the new law one can now be a free rider, benefitting from negotiations that have been paid for by your fellow workers. (One is not required to join the union but all workers in a unionized workplace must pay negotiating costs.) The problem, of course, is that, once payment is no longer required, many choose not to pay, unions no longer have the wherewithal to negotiate, and salaries and benefits go down. All workers, union and non-union alike, pay the price.

It strikes me that, at the moment, we are witnessing America’s economic upper class—a group that is benefitting from a return to Gilded Age income disparities—fighting to hold on to everything it has. Because it is terrified that America’s changing demographics will cut into its share, it is relying on the GOP to hold the line, and the GOP’s anti-union efforts in the Midwest are part of that effort.

The Supreme Court’s Citizen’s United decision already tilted the playing field towards large corporations. Their money didn’t swing the past presidential election, but it has been having an outsized influence in state politics. The attacks on unions by GOP governors and state legislatures are just the next step. After all, once you undermine organizations that represent the collective power of workers, all you have are individuals. As Chait explains it, “Management doesn’t have a collective action problem — it can represent itself. Labor needs to pool its resources to gain either negotiating leverage or political power.”

Because of union successes from the 1930’s through the 1960’s, people came to see unions as powerful. But for a variety of reasons, unions have declined in recent decades and the middle class has, partially as a result, seen its income levels stagnate. (This is even truer in the south, where unions have been traditionally weak and where take-home pay is considerably lower.) Rachel’s novel addresses the challenges that unions face.

A strike has been organized at a large New York university, which is Olympia in the book and Columbia in real life. Two organizers, Jack and Rosie, are talking in a diner, and one of them quotes The Communist Manifesto (with its wonderful echo of The Tempest*):

“I’m a Marxist,” Jack says. “This is my creed.” And he quotes, “ ‘Uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation, distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man’—people,” he interrupts himself, making a face, “but the quote doesn’t work if you say ‘people,’ so man—is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life and his relation with his kind.” Meaning that—“

“I know what it means,” I say, with some asperity. “I have read Marx.”

Jack grins at me again. “So what does it mean?” he says. “In twenty-five words or less.”

“I suppose it means that we can’t have any illusions anymore about how brutal everything is,” I say slowly. “How brutal everything is, and then how we have to be honest about that. About why. We can’t say it’s fate, or God’s will, or destiny, anything solid, anything holy. It’s just—a few stupid people with power lording it over the rest of us. And we help them dominate us, first by working for them and making them rich, and then by buying whatever they want us to buy, and then by believing whatever they want us to believe, and then by telling ourselves that it’s our own idea. And then it is our idea, because if you have something inside you long enough, then it is you, no matter how much you hate it, no matter how sick it makes you—then it is you, and at least part of you does everything you can to hold onto it. And then, to add insult to injury, we enjoy the way they dominate us, we enjoy the little crumbs they throw at us, because what else are we going to do with ourselves? How else are we doing to keep on living?!”

Well, I certainly didn’t expect to get this upset.

Rachel’s title, Leaps of Faith, gives us a sense of how the strike in the novel works out. Against overwhelming odds and against all probability, Olympia’s clerical workers prevail, just as they did at Columbia University in the 1985 strike that inaugurated their first union contract, and as they have in subsequent strikes and negotiations.

But while idealistic, the novel is not naïve as it shows just how hard it is to organize workers. One difficulty is getting people to attend evening meetings when they are already worn out by their day jobs, especially when they have families. Another is getting workers to muster up enough courage to fight back against a powerful employer—and for that matter, the courage to move beyond their fatalism.

We learn by watching Rachel’s characters discover just how how empowered they are once they are unionized. Union members are more likely to feel in control of their destinies and, as a result, are more likely to have progressive rather than reactionary politics.

Incidentally, along with the strike at Olympia, the book also charts the decision by two gay men to get married. Whoever could have predicted that, twelve years after the novel was written (in 2000), same sex marriage would be in better shape than the union movement? The organizing passages seem particularly relevant now.

Rachel helps us understand how to keep hope alive. For instance, she notes that it is empowering merely to notice what is going on. As Jack says,

I find it a relief to say the way things are. It makes me feel—I don’t know. Exhilarated. You feel bad about it. But still, you don’t despair.

And then, remarking on Rosie’s outburst about the apparently hopelessness of it all, he adds,

What you just did, that wasn’t despair. You just feel bad that it takes other people so long to see what you already know. But you don’t give up on them.

Start by facing up to what is going on. Hope will follow and, after hope, action.

Prospero’s speech from The Tempest:

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits, and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp’d tow’rs, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve,

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on; and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.

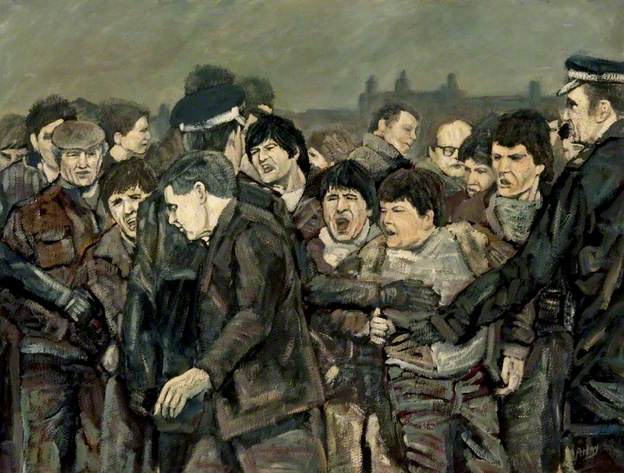

A note on the artist: The artist’s work can be found at www.bbc.co.uk/arts/yourpaintings/paintings/the-police-and-the-picket-lines-84396.