Thursday

As John Bolton, Liz Cheney, and Bret Stephens urge war on Iran for striking Saudi Arabia’s oil fields, I turn once again to that great anti-war classic, The Iliad. I’ve written in the past how classics scholar Caroline Alexander believes the poem’s major theme is the waste and tragedy of war, not heroic glory. In the poem’s climactic moment, Homer shows what it takes to engage diplomatically with an enemy.

While Donald Trump, to his credit, appears reluctant to follow the hawks into another Middle East conflict, he has so botched his diplomatic options—by withdrawing from the Iran nuclear agreement and alienating allies—that it’s anyone’s guess what will happen next. The president needs to check out the interchange between Priam and Achilles.

More on that in a moment. Let’s look first at Alexander’s argument that Homer is an anti-war poet, which goes against the perception that epics are predominantly about glorifying heroes. Alexander counters that

no subsequent work of literature of any genre has ever made the fate of the entirety of any people more vividly and tragically unambiguous. In the epic’s finale, the import of its title becomes clear: the Iliad relates the fate of the soon-to-be-extinct city of Ilion. Through the speeches of Andromache and Priam, Homer conjures the individual destructions that will accompany the catastrophic fall of Troy: the Trojan War represents Total War.

Alexander notes that our distorted view of the Iliad can be traced back to those elite schools whose “classically-based curriculum was dedicated to inculcating into the national’s future manhood the desirability of ‘dying well’ for king and country.” This is not how original audiences would have seen the work, however. As refugees from the fall of the Mycenean world, they would have found in The Iliad scenes that recalled their own suffering:

The Iliad speaks casually of suppliant exiles who have fled their homes after murdering men of high estate, the selling of captives into slavery, the looting of cities, threats of usurpation, all of which provide murky glimpses into the period of upheaval in which its tradition was forged. It is to such actual memories that we may owe the Iliad’s most haunting images. Priam’s predictions that he will live to see “innocent children / hurled to the ground in the terror of battle’” and that his own body will be ripped raw by his dogs, pitifully revealing his old man’s private parts—the shocking specificity of such scenes arise, surely, not from poetic invention but historic memory.

Throughout her book, Alexander makes it clear that Achilles would choose peace over glory. Here’s what he has to say to Ajax and Odysseus early in the poem:

Either

if I stay here and fight beside the city of the Trojans,

my return home is gone, but my glory shall be everlasting;

but if I return home to the beloved land of my fathers,

the excellence of my glory is gone, but there will be a long life

left for me, and my end in death will not come to me quickly.

And this would be my counsel to others also, to sail back

home again.”

To be sure, he will later reengage in the fighting, but that’s to avenge Patroklus, not for glory. Alexander concludes that the Iliad

never betrays its subject, which is war. Honoring the nobility of a soldier’s sacrifice and courage, Homer nonetheless determinedly concludes his epic with a sequence of funerals, inconsolable lamentation, and shattered lives. War makes stark the tragedy of mortality. A hero will have no recompense for death, although he may win glory.

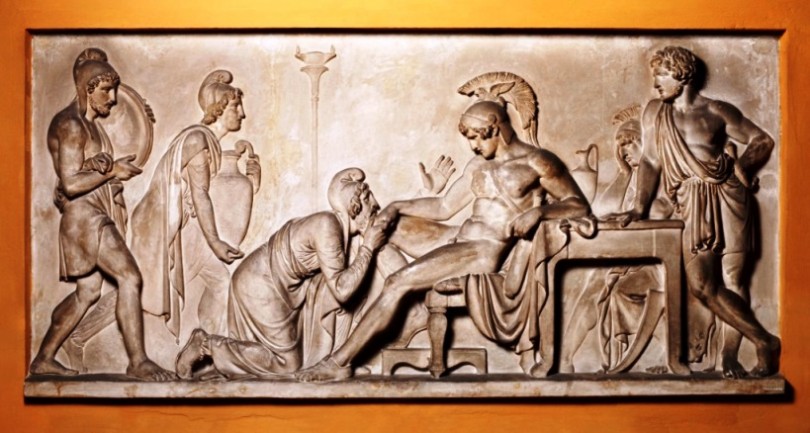

And now for the extraordinary encounter of Priam and Achilles, where each recognizes the humanity of the other and which offers hope of reconciliation between enemies. Priam has ventured out, in peril of his own life, to beg the body of Hector from Achilles, and Achilles sees his own sorrow in the old man’s request.

“Honor then the

gods, Achilles, and take pity upon me

remembering your father, yet I am still more pitiful;

I have gone through what no other mortal on earth

has gone through

I put my lips to the hands of the man who has killed

my children.”

So he spoke, and stirred in the other a passion of grieving

for his own father. He took the old man’s hand and

pushed him

gently away, and the two remembered, as Priam

sat huddled

at the feet of Achilles and wept close for manslaughtering

Hector

and Achilles wept now for his own father, now again

for Patroklos. The sound of their mourning moved

in the house.

The encounter leads Achilles to offer hospitality to Priam, and the two agree to a nine-day truce that Alexander compares to the famous Christmas Truce between German and British soldiers during World War I. Alexander writes,

Priam and Achilles meet in the very twilight of their lives. Their extinction is certain and there will be no reward to behaving well, and yet, in the face of implacable fate and an indifferent universe, they mutually assert the highest ideals of their humanity. Like all cease-fires, the truce that Achilles pledges for Priam floats the specter of a wistful opportunity.

As in the Iliad, today we have powerful figures rooting for bloodshed. Hera and Athena, determined that Troy be utterly destroyed, have their modern equivalents. Yet against these implacable forces, two suffering humans carve out a different path, at least for a brief moment. Art sees possibilities that political leaders miss.