Spiritual Sunday

Many people go to religious services when they are traumatized, which makes closing the church doors during this crisis particularly unsettling. A couple of weeks ago I wrote an essay critical of millenarians defying prohibitions against large gatherings, but today I use Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year (1722) to offer a slightly more sympathetic account.

Not that I agree with these rule-breaking churchgoers. Defoe, however, reminds me how desperate they are.

Journal of the Plague Year is a novel about the great London plague of 1665. To write it, Defoe drew heavily on a journal kept by his uncle Henry Foe (H.F.), whom he sets up as the narrator.

H.F. reports that Londoners flock to churches in the early stages of the plague:

The Government encouraged [the population’s] devotion, and appointed public prayers and days of fasting and humiliation, to make public confession of sin and implore the mercy of God to avert the dreadful judgement which hung over their heads; and it is not to be expressed with what alacrity the people of all persuasions embraced the occasion; how they flocked to the churches and meetings, and they were all so thronged that there was often no coming near, no, not to the very doors of the largest churches. Also there were daily prayers appointed morning and evening at several churches, and days of private praying at other places; at all which the people attended, I say, with an uncommon devotion.

Of course, we now know that such large social gatherings accelerate pandemics, which Londoners themselves quickly learn. Nevertheless, a fair number keep attending services “even in the most dangerous times.” H.F adds,

and though it is true that a great many clergymen did shut up their churches, and fled, as other people did, for the safety of their lives, yet all did not do so. Some ventured to officiate and to keep up the assemblies of the people by constant prayers, and sometimes sermons or brief exhortations to repentance and reformation, and this as long as any would come to hear them.

One can imagine current-day legislators bestowing “essential service” status on these London churches given how people use them, in their final hours, for spiritual solace and psychological relief:

It was indeed a lamentable thing to hear the miserable lamentations of poor dying creatures calling out for ministers to comfort them and pray with them, to counsel them and to direct them, calling out to God for pardon and mercy, and confessing aloud their past sins. It would make the stoutest heart bleed to hear how many warnings were then given by dying penitents to others not to put off and delay their repentance to the day of distress; that such a time of calamity as this was no time for repentance, was no time to call upon God. I wish I could repeat the very sound of those groans and of those exclamations that I heard from some poor dying creatures when in the height of their agonies and distress, and that I could make him that reads this hear, as I imagine I now hear them, for the sound seems still to ring in my ears.

H.F. goes on to describe another stage of the plague where church attendance spikes. When things get really bad, he theorizes, people feel they have little to lose:

As I have mentioned how the people were brought into a condition to despair of life and abandon themselves, so this very thing had a strange effect among us for three or four weeks; that is, it made them bold and venturous: they were no more shy of one another, or restrained within doors, but went anywhere and everywhere, and began to converse. One would say to another, ‘I do not ask you how you are, or say how I am; it is certain we shall all go; so ’tis no matter who is all sick or who is sound’; and so they ran desperately into any place or any company.

Social distancing is deliberately abandoned at this point:

As it brought the people into public company, so it was surprising how it brought them to crowd into the churches. They inquired no more into whom they sat near to or far from, what offensive smells they met with, or what condition the people seemed to be in; but, looking upon themselves all as so many dead corpses, they came to the churches without the least caution, and crowded together as if their lives were of no consequence compared to the work which they came about there. Indeed, the zeal which they showed in coming, and the earnestness and affection they showed in their attention to what they heard, made it manifest what a value people would all put upon the worship of God if they thought every day they attended at the church that it would be their last.

H.F. acknowledges that church attendance goes down somewhat when people realize that individuals may be carrying the disease even when they are asymptomatic (“apparently in good health”). Even in those cases, however, churches don’t close down altogether:

Yet I observed that after people were possessed, as I have said, with the belief, or rather assurance, of the infection being thus carried on by persons apparently in health, the churches and meeting-houses were much thinner of people than at other times before that they used to be. For this is to be said of the people of London, that during the whole time of the pestilence the churches or meetings were never wholly shut up, nor did the people decline coming out to the public worship of God, except only in some parishes when the violence of the distemper was more particularly in that parish at that time, and even then no longer than it continued to be so.

Indeed nothing was more strange than to see with what courage the people went to the public service of God, even at that time when they were afraid to stir out of their own houses upon any other occasion; this, I mean, before the time of desperation, which I have mentioned already. This was a proof of the exceeding populousness of the city at the time of the infection, notwithstanding the great numbers that were gone into the country at the first alarm, and that fled out into the forests and woods when they were further terrified with the extraordinary increase of it. For when we came to see the crowds and throngs of people which appeared on the Sabbath-days at the churches, and especially in those parts of the town where the plague was abated, or where it was not yet come to its height, it was amazing.

H.F. does not judge anyone, either those pastors who flee or those who stay. The former should not be condemned for their lack of fortitude, he says, and the latter should not become boastful and condemn others. None of us knows how he or she would respond in similar circumstances:

A plague is a formidable enemy, and is armed with terrors that every man is not sufficiently fortified to resist or prepared to stand the shock against. It is very certain that a great many of the clergy who were in circumstances to do it withdrew and fled for the safety of their lives; but ’tis true also that a great many of them stayed, and many of them fell in the calamity and in the discharge of their duty.

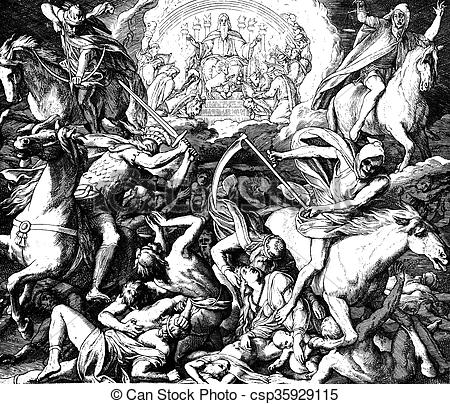

…[U]pon the whole, an allowance of charity might have been made on both sides, and we should have considered that such a time as this of 1665 is not to be paralleled in history, and that it is not the stoutest courage that will always support men in such cases. I had not said this, but had rather chosen to record the courage and religious zeal of those of both sides, who did hazard themselves for the service of the poor people in their distress, without remembering that any failed in their duty on either side. But the want of temper among us has made the contrary to this necessary: some that stayed not only boasting too much of themselves, but reviling those that fled, branding them with cowardice, deserting their flocks, and acting the part of the hireling, and the like. I recommend it to the charity of all good people to look back and reflect duly upon the terrors of the time, and whoever does so will see that it is not an ordinary strength that could support it. It was not like appearing in the head of an army or charging a body of horse in the field, but it was charging Death itself on his pale horse; to stay was indeed to die, and it could be esteemed nothing less, especially as things appeared at the latter end of August and the beginning of September, and as there was reason to expect them at that time…

Besides, if God gave strength to some more than to others, was it to boast of their ability to abide the stroke, and upbraid those that had not the same gift and support, or ought not they rather to have been humble and thankful if they were rendered more useful than their brethren?

The same charity should be extended to our own healthcare and frontline workers who have chosen to retire from the battle, even as we applaud those who keep working. H.F., incidentally does his own applauding at the end of the narrative:

I think it ought to be recorded to the honour of such men, as well clergy as physicians, surgeons, apothecaries, magistrates, and officers of every kind, as also all useful people who ventured their lives in discharge of their duty, as most certainly all such as stayed did to the last degree; and several of all these kinds did not only venture but lose their lives on that sad occasion.

I was once making a list of all such, I mean of all those professions and employments who thus died, as I call it, in the way of their duty; but it was impossible for a private man to come at a certainty in the particulars. I only remember that there died sixteen clergymen, two aldermen, five physicians, thirteen surgeons, within the city and liberties before the beginning of September. But this being, as I said before, the great crisis and extremity of the infection, it can be no complete list.

Thanks to social media, we have many more options regarding worship, not to mention a much better understanding of epidemics. Nevertheless, Defoe’s novel reminds us how important church is in tough times and why it has been so difficult for legislators to order church doors closed. And for many of the faithful to stay away.