Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, write to me at rrbates1951@gmail.com. I’ll subscribe you via Mailchimp for the weekly or email you directly for the daily (your choice). Comments may also be sent to this address. I promise not to share your e-mail with anyone.

Monday

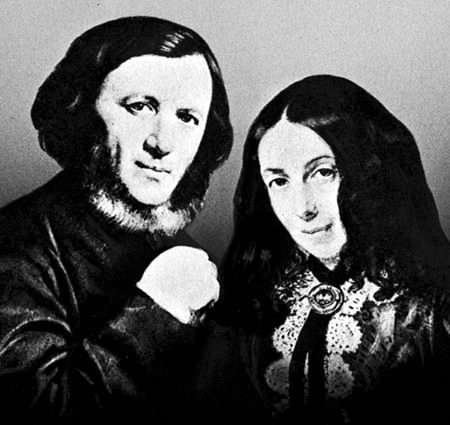

My faculty reading group has been discussing the poetry of Robert Browning, and as yesterday was Julia’s and my 52nd wedding anniversary, I share today a marriage love poem written to him by his spouse. Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s “How do I love you, let me count the ways” is one of the best-known love poems—is there anyone who hasn’t encountered its opening line?—but it takes on special meaning when you think of it as arising out of a marriage.

Robert and Elizabeth married over the strenuous objection of her father—he disinherited her—and Robert persuaded her to publish Sonnets of the Portuguese, which she feared were too personal. One of his pet names for her was “my little Portuguese,” which explains the title.

Speaking from my own experience, there are times in marriage when one experiences oceanic feelings of love and times when one experiences moments of quiet tenderness. Barrett Browning touches on both. She knows that her love for her husband has stretched her soul beyond physical parameters—beyond depth and breadth and height—but also that this love dwells in “every day’s most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.” Any number of domestic moments could behind her declaration that “I love thee with the breath,/ Smiles, tears, of all my life.” This love she associates with humankind’s noblest ends—“I love thee freely, as men strive for right”—and knows that it transcends the egotistical self: she love purely, not transactionally, not for praise.

It sounds as though she may once have lost her childhood religious faith—she mentions “lost saints”—but she remembers the passionate immersion of that time, and now regards marital love and divine love as indistinguishable. Love, after all, is the foundation—”the love that moves the sun and the other stars,” as Dante puts it—and this love is at once domestic and divine.

And because it is, she can imagine it transcending death itself. “If God choose, I shall but love thee better after death,” she writes.

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

I love thee to the level of every day’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for right.

I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints. I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life; and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

The poem has traveled quite a distance from the poet’s initial claim that she will be enumerating love’s aspects. The matter-of-fact opening contrasts with, and therefore serves to accentuate, the way that love refuses to be confined by time, space, or life itself.

So happy anniversary, my dear. My love for you over these 52 years—53 actually—has deepened and expanded in ways I could never have imagined.