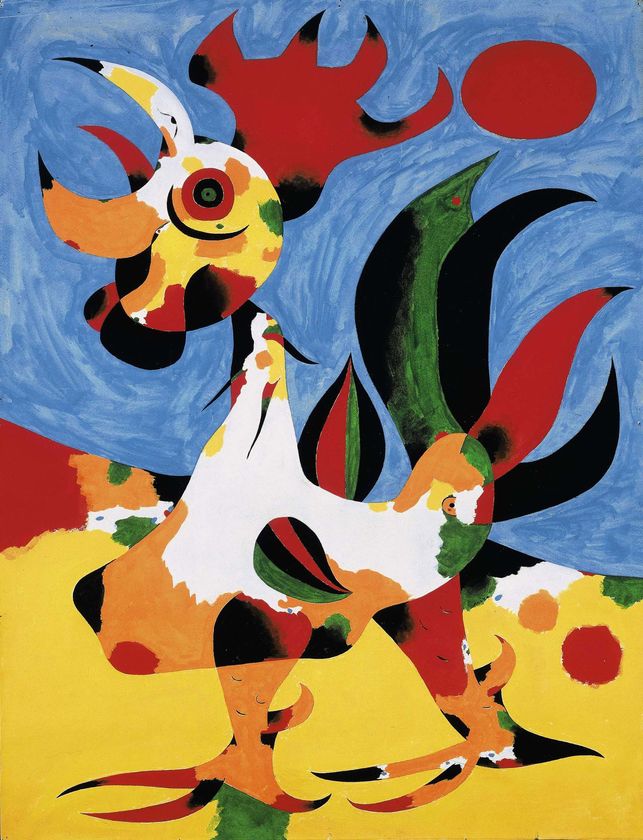

Joan Miro, “Le Coq”

Joan Miro, “Le Coq”

Spiritual Sunday

This is the story of a student basketball player whose life has been changed by the mystic religious poetry of Henry Vaughan.

Okay, so “changed” might be an exaggeration. But the 17th century metaphysical poet is helping Brian sort through a series of life reversals in ways that I find inspiring.

Brian, a center on the very successful St. Mary’s College of Maryland basketball team (last year we reached the Sweet 16 in the NCAA Division III tournament), three weeks ago suffered the sixth concussion of his basketball career. Recent research into athletic concussions is revealing them to cause severe long-term brain damage, and Brian was concerned.

Nor is the concussion Brian’s only problem. He has recently been diagnosed with Lyme disease. Then, for good measure, a drunk driver ran a red light and plowed into the side of his car, causing some whiplash in his neck (not to mention depriving him of a car). The series of events prompted Brian to start thinking of things besides basketball.

Brian is enrolled in my early British Literature survey class and was struck, in our conversations of King Lear, by how the king manages to find, in the love of Cordelia, a force that transcends all his reversals of fortune.

Then we read Henry Vaughan’s “The World” and “They Are All Gone into the World of Light” and something clicked. In his journal entry on the Vaughan poem “Cock-Crowing” (printed below), Brian found that he couldn’t stop writing.

The poem makes parallels between the cock joyously greeting the sun and the poet greeting God. Brian found himself particularly taken by the stanza where Vaughan talks about God’s “hand” shining through the crowing cock (and by extension, through the crowing poet):

O thou immortal light and heat!

Whose hand so shines through all this frame,

That by the beauty of the seat,

We plainly see, who made the same.

Seeing thy seed abides in me,

Dwell thou in it, and I in thee.

When Brian came by for his conference, I learned that he has decided to leave basketball and begin focusing on discovering who he is and what he wants to do with his life—maybe become a teacher and a coach, maybe a lawyer, he doesn’t know yet. But he does know that it is important to find his center, and he was hoping that an essay on Vaughan would help him in the process.

Because he felt he was starting to see clearly in a world filled with a lot of darkness, we talked about images of light in Vaughan’s poetry. “The World” (which I have posted on here) is the poem that initially caught his attention. As he writes in his journal (shared here with his permission), he was struck by the poem’s

emphasis that Earth was a “dark abode” and that people focus too much on everyday material matters and that they tend to ignore the most important matter, “Great rule of pure Light,” or God. This poem struck home at least for me since it reminded me that there is more to this world than what goes on according to a day-to-day basis. Especially now for me after stepping away from basketball, discovering I had Lyme disease and battling it, plus unfortunately getting hit by a car I really learned to appreciate everything going on around me.

Brian then plunged into “Cock-Crowing.” Remember that this is an informal journal, one of 10 one-thousand-word entries that I ask them to write in the course of the semester (in addition to a final essay and an annotated bibliography). It’s meant to be written roughly and quickly. What I love about Brian’s concluding passage below is his passion and his excitement over his growing ability to interpret poetry. His journal doesn’t read like an empty academic assignment:

I hate to skip over some great lines, but I will finish with two other big ones (at least in my eyes) that help bring about the main idea for the poem.

The first would be, “This veil, I say, is all the cloak/And cloud which shadows thee from me.” What all this means is that there is something keeping God and man separated. Now, this only applies to Earth not heaven. This is because the use of “veil” is referring to flesh. Thus our flesh or human body is the only separation from God, it “clouds” and “shadows” God from us. This leads into the last line I wish to explore, “O take it off! Or till it flee…stay with me!” Here Vaughan comes out and is basically saying, let me die, “take it off,” rid me of the flesh that keeps me from God. Then by saying “Or till it Flee..stay with me” he seems to say that as long as he is alive, he asks God to live with him through his connection embedded in his soul.

I’m not going to give Vaughan all the credit for Brian’s search for things that matter. He is a contemplative student who was already engaged in an existential exploration before he came across the poet’s works. But Vaughan gave Brian images and a vision that helped him put a framework around his search.

Student engagement such as this is what keeps me passionate about teaching. Here’s the poem in its entirety:

Cock-Crowing

By Henry Vaughan

Father of lights! what sunny seed,

What glance of day has thou confined

Into this bird? To all the breed

This busy ray thou has assigned;

Their magnetism works all night,

And dreams of Paradise and light.

Their eyes watch for the morning hue,

Their little grain expelling night

So shines and sings, as if it knew

The path unto the house of light.

It seems their candle, howe’r done,

Was tinned and lighted at the sun.

If such a tincture, such a touch,

So firm a longing can impower,

Shall thy own image think it much

To watch for thy appearing hour?

If a mere blast so fill the sail,

Shall not the breath of God prevail?

O thou immortal light and heat!

Whose hand so shines through all this frame,

That by the beauty of the seat,

We plainly see, who made the same.

Seeing thy seed abides in me,

Dwell thou in it, and I in thee.

To sleep without thee, is to die;

Yea, ’tis a death partakes of hell:

For where thou dost not close the eye

It never opens, I can tell.

In such a dark, Egyptian border,

The shades of death dwell and disorder.

If joys and hopes and earnest throes,

And hearts, whose pulse beats still for light

Are given to birds; who, but thee, knows

A love-sick soul’s exalted flight?

Can souls be tracked by any eye

But his, who gave them wings to fly?

Only this veil which thou has broke,

And must be broken yet in me,

This veil, I say, is all the cloak

And cloud which shadows thee from me.

This veil thy full-eyed love denies,

And only gleams and fractions spies.

O take it off! Make no delay,

But brush me with thy light, that I

May shine unto a perfect day,

And warm me at thy glorious eye!

O take it off! or till it flee,

Though with no lily, stay with me!

2 Trackbacks

[…] is writing an essay about Henry Vaughan (see my post on him and the poem “Cock Crowing” here) has me thinking about light and dark imagery in the poetry of this 17th century mystical Anglican. […]

[…] sacrifice a cock to Asclepius? As Henry Vaughan writes in a poem I have posted on, the cock affirms life, calling forth the […]