Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share it with anyone.

Monday

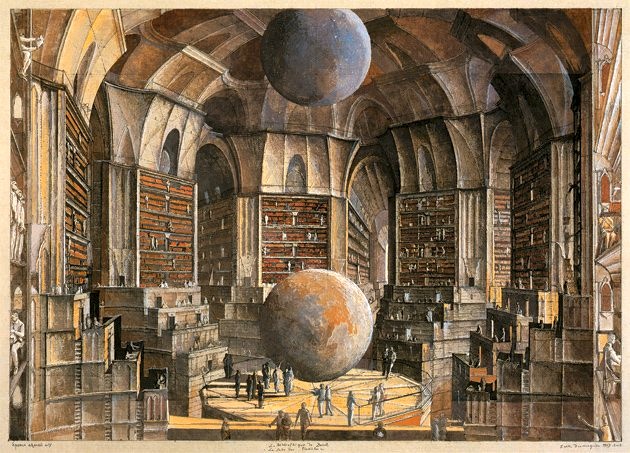

Yesterday my friend Sue Schmidt took us to a most remarkable bookstore. Harrisburg’s Midtown Scholar, which contains both new and used books (sometimes grouped together on the same shelf), is a veritable labyrinth. One thinks one has reached its outer reaches, only to discover underground caverns with yet more treasures. As I wandered through whole collections of old volumes—sometimes works by George Eliot, Walter Scott, and William Makepeace Thackeray, sometimes Zane Grey westerns and Nancy Drew mysteries—I thought of Jorge Luis Borges’s short story “The Library of Babel.” The story begins as follows:

The universe (which others call the Library) is composed of an indefinite, perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries. In the center of each gallery is a ventilation shaft, bounded by a low railing. From any hexagon one can see the floors above and below—one after another, endlessly. The arrangement of the galleries is always the same: Twenty bookshelves, five to each side, line four of the hexagon’s six sides; the height of the bookshelves, floor to ceiling, is hardly greater than the height of a normal librarian. One of the hexagon’s free sides opens onto a narrow sort of vestibule, which in turn opens onto another gallery, identical to the first-identical in fact to all. To the left and right of the vestibule are two tiny compartments.

While the Midtown Scholar is not this symmetrical—and certainly not this vast—I did have the sense that it could go on and on. And there were two little rooms amongst the bookshelves such as one finds in Borges’s library: “One is for sleeping, upright; the other, for satisfying one’s physical necessities.” Only in this case, one was for men to satisfy their physical necessities, one was for women. And there were also staircases which, while not spiral (as in Borges’s library) did seem to reach “upward and downward into the remotest distance.”

And there’s yet another similarity. Borges reports,

Light is provided by certain spherical fruits that bear the name “bulbs.” There are two of these bulbs in each hexagon, set crosswise. The light they give is insufficient, and unceasing.

To be sure, the Library of Babel is about possibility rather than reality, containing as it does all books that could be written as well as those that have been written. That’s because one can find every combination of letters. Or at least, this is posited by a philosopher librarian, who posits,

In this library, there are no two identical books. From those incontrovertible premises, the librarian deduced that the Library is “total”—perfect, complete, and whole—and that its bookshelves contain all possible combinations of the twenty-two orthographic symbols (a number which, though unimaginably vast, is not infinite)—that is, all that is able to be expressed, in every language.

Because of this, any attempt to weed books from the collection is meaningless. Borges gives two reasons why:

One, that the Library is so huge that any reduction by human hands must be infinitesimal. And two, that each book is unique and irreplaceable, but (since the Library is total) there are always several hundred thousand imperfect facsimiles—books that differ by no more than a single letter, or a comma.

So okay, we’ve strayed far from any bookstore or library ever. And yet, when I was looking at the Margaret Atwood selection, I found six hardback duplicates of The Blind Assassin, which I’ve been meaning to add to my own collection. One was new and the others were used, and while they at first seemed the same, tiny little imperfections meant that each carried a different price. So instead of paying $20 or $12 or $9.50, I was able to purchase a copy for $7.25 (the book jacket sporting a slight tear and someone’s name inscribed inside the front cover). So not identical.

Boges’s story is, at one level, a satire of the Enlightenment project to bring order to the world—in this case, of librarians (and he himself was a librarian) to organize all that has been written and will be written. The symmetrical arrangement of the Library of Babel is mocked by its infinite space, which shows that any attempts at arrangement are futile and even ridiculous.

I felt somewhat put in my place by the Midtown Scholar: its holdings are so wide-ranging that I was confronted with how relatively little I have read and how small I am. Although I have spent most of my life reading literature, especially fiction, there were scores of authors and the novels, many with glowing jacket blurbs, that I haven’t even heard of. And then I think of all the novels that the bookstore didn’t have and of which I will remain in ignorance. As Borges puts it, “The certainty that some bookshelf in some hexagon contained precious books, yet that those precious books were forever out of reach, was almost unbearable.”

I identify with Borges when he talks about realizing that his youthful ambitions never had a chance of being realized. In his case, it was organizing the important works, in my case it was becoming familiar with them. As it is, I have barely made a dent in what there is to be read. As the soon-to-be-blind Borges puts it, he has traveled no more than a short distance from “the hexagon where I was born”:

Now that my eyes can hardly make out what I myself have written, I am preparing to die, a few leagues from the hexagon where I was born. When I am dead, compassionate hands will throw me over the railing; my tomb will be the unfathomable air, my body will sink for ages, and will decay and dissolve in the wind engendered by my fall, which shall be infinite.

“The universe (which many call the Library)” is a vast abyss of unread books. The better the bookstore, the more I experience the abyss.