Note: If you wish to receive, via e-mail, (1) my weekly newsletter or (2) daily copies of these posts, notify me at [email protected] and indicate which you would like. I promise not to share your e-mail address with anyone. To unsubscribe, send me a follow-up email.

Thursday

Reader and friend Mike Hazard alerted me to a politician using the Scarlet Letter in a recent press conference. Although MSNBC host Katie Phang called it a stunt and “performative nonsense,” I think there might be something to it. Here’s historian Heather Cox Richardson’s report:

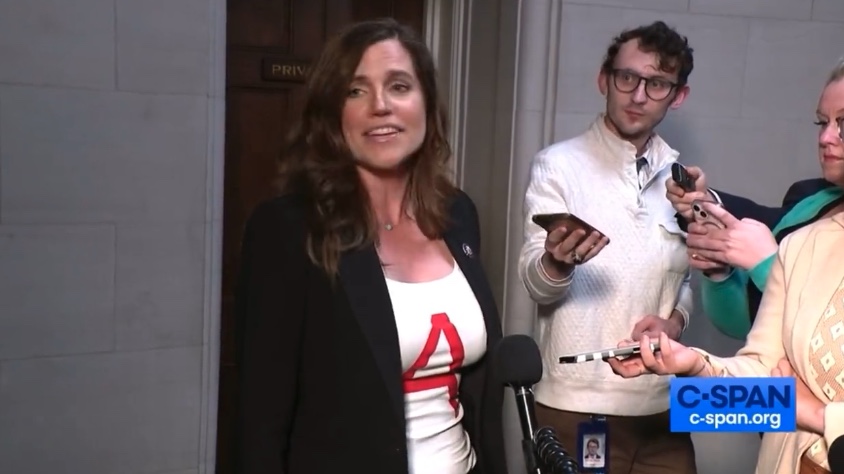

Representative Nancy Mace (R-SC) entered the Republican candidate forum today wearing a white T-shirt with a red letter “A” on it, saying she was doing so because of the backlash she faced as “a woman up here, and being demonized for my vote and for my voice.” Mace, one of the eight House Republicans who voted to get rid of former speaker Kevin McCarthy, said the A was her “scarlet letter,” an apparent reference to Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1850 novel involving a woman forced to wear a scarlet A after giving birth to a child without identifying the father.

While I know barely anything about Mace (Wikipedia is my main source of information on her), I know that some consider her to be what passes for a moderate in the GOP these days—and that people were therefore surprised when she joined with Matt Gaetz and the “crazy caucus” against House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, the first time in American history a Speaker has been voted out by his own party. She’s considered a moderate because she believes that victims of rape and incest should indeed have access to abortion. (Apparently she herself was raped by a classmate at age 16.) Also, at a time when some on the right are attacking birth control itself, she’s an advocate, which I guess is something.

At any rate, it’s interesting that she identifies with a book about an unwanted pregnancy although her “stunt” is not about reproduction. Rather, she is addressing those fellow Republicans who are furious about her vote against McCarthy. Her self-defense bolsters her claims of moderation. McCarthy lost her vote, she claims, because he “did not follow through on pushing her legislation to address the country’s rape-kit backlog, expand access to birth control, adopt a balanced budget amendment and create an alert system that would notify people when there is a mass shooting.”

Turning to the novel, if Hester Prynne had access to abortion, she never would have been exhibited on the scaffold or shunned by society. She finds her punishment excruciating:

The unhappy culprit sustained herself as best a woman might, under the heavy weight of a thousand unrelenting eyes, all fastened upon her, and concentrated at her bosom [where the scarlet letter is placed]. It was almost intolerable to be borne. Of an impulsive and passionate nature, she had fortified herself to encounter the stings and venomous stabs of public contumely, wreaking itself in every variety of insult; but there was a quality so much more terrible in the solemn mood of the popular mind, that she longed rather to behold all those rigid countenances contorted with scornful merriment, and herself the object. Had a roar of laughter burst from the multitude,—each man, each woman, each little shrill-voiced child, contributing their individual parts,—Hester Prynne might have repaid them all with a bitter and disdainful smile. But, under the leaden infliction which it was her doom to endure, she felt, at moments, as if she must needs shriek out with the full power of her lungs, and cast herself from the scaffold down upon the ground, or else go mad at once.

Hawthorne describes the Puritan audience as “stern enough to look upon her death, had that been the sentence, without a murmur at its severity.” We also learn that her cuckolded husband finds the punishment appropriate: “She will be a living sermon against sin, until the ignominious letter be engraved upon her tombstone,” he tells a fellow onlooker. In such people one sees our own forced birth fundamentalists. those that would have a 12-year-old give birth to her father’s child and a rape victim to her rapist’s. And that would force a woman to risk her health and life by carrying a non-viable fetus to term.

Mace, who is well acquainted with the neo-Puritan sensibilities of her fellow Republicans, is uncomfortable that their ire has suddenly been turned on her. She is discovering that any party member who shows even a hint of moderation will suffer their slings and arrow, and she channels Hester to give her the strength to bear up against such attacks. Her showy display of a scarlet letter is akin to Hester’s own boldness:

On the breast of her gown, in fine red cloth, surrounded with an elaborate embroidery and fantastic flourishes of gold-thread, appeared the letter A. It was so artistically done, and with so much fertility and gorgeous luxuriance of fancy, that it had all the effect of a last and fitting decoration to the apparel which she wore; and which was of a splendor in accordance with the taste of the age, but greatly beyond what was allowed by the sumptuary regulations of the colony.

The scarlet letter for both Mace and Hester is designed to create a sensation. Here’s the effect of Hester’s letter:

But the point which drew all eyes, and, as it were, transfigured the wearer,—so that both men and women, who had been familiarly acquainted with Hester Prynne, were now impressed as if they beheld her for the first time,—was that Scarlet Letter, so fantastically embroidered and illuminated upon her bosom. It had the effect of a spell, taking her out of the ordinary relations with humanity, and enclosing her in a sphere by herself.

Perhaps Mace, feeling martyred herself, likes the beauty that martyrdom conveys upon Hester. I can imagine the legislator thrilling to the following passage when she read Scarlet Letter in high school or college:

The young woman was tall, with a figure of perfect elegance on a large scale. She had dark and abundant hair, so glossy that it threw off the sunshine with a gleam, and a face which, besides being beautiful from regularity of feature and richness of complexion, had the impressiveness belonging to a marked brow and deep black eyes. She was lady-like, too, after the manner of the feminine gentility of those days; characterized by a certain state and dignity, rather than by the delicate, evanescent, and indescribable grace, which is now recognized as its indication. And never had Hester Prynne appeared more lady-like, in the antique interpretation of the term, than as she issued from the prison. Those who had before known her, and had expected to behold her dimmed and obscured by a disastrous cloud, were astonished, and even startled, to perceive how her beauty shone out, and made a halo of the misfortune and ignominy in which she was enveloped.

In light of her familiarity with Hester’s imprisonment, I find it interesting that, as a South Carolina House member, Mace was instrumental in passing a law exempting imprisoned pregnant women from shackles. Maybe the book made her more sensitive to the issue.

For all the positive things one can say about Mace, however, she still advocates a 12-15-week limit for abortions—before some women even know they are pregnant–after which she is in favor of unleashing state power and public opprobrium against offenders. She’s all too willing to become one of those censorious Puritans herself. Nor, as far as I can tell, has she shown any inclination to support programs for new mothers or for impoverished families with kids. Her support for a “balanced budget”—unless it included cuts to the military and significantly higher taxes on the wealthy—would ravage social safety net programs. The Puritans, at least, allow Hester to have a house and a garden plot.

Indeed, for all the seemingly laudable reasons Mace gave for voting against McCarthy, I wonder whether that was the actual stunt. After all, if one only voted for candidates who endorsed all one’s pet projects, no one would ever be elected to Speaker. Perhaps, Mace thinks, she can get away with her quasi-moderation if she joins—on this vote—with those who want to “burn the whole place down” (McCarthy’s words).

Still, I always enjoy seeing someone making use of a classic.