Spiritual Sunday

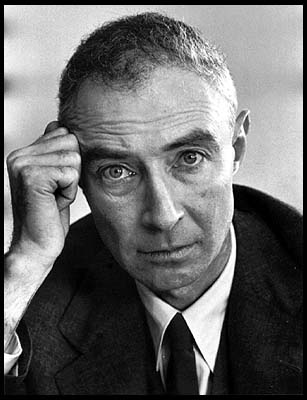

What would attract the father of the nuclear bomb to a devotional poet like George Herbert?

That J. Robert Oppenheimer was drawn to the 17th-century Anglican rector I learn from American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, written by Kai Bird (a former Carleton classmate of mine) and Martin J. Sherwin. (A tip to my father for alerting me to the book.) The story they relate involves a dinner party involving Oppenheimer, theologian Reinhold Neibuhr, and diplomat George Kennan, the architect of the Soviet containment doctrine. Discovering that Kennan did not know Herbert’s poetry, Oppenheimer apparently introduced him to “The Pulley.” Here’s the poem:

The Pulley

When God at first made man,

Having a glass of blessings standing by;

Let us (said he) pour on him all we can:

Let the world’s riches, which dispersed lie,

Contract into a span.

So strength first made a way;

Then beauty flowed, then wisdom, honor, pleasure:

When almost all was out, God made a stay,

Perceiving that alone, of all his treasure,

Rest in the bottom lay.

For if I should (said he)

Bestow this jewel also on my creature,

He would adore my gifts instead of me,

And rest in Nature, not the God of Nature:

So both should losers be.

Yet let him keep the rest,

But keep them with repining restlessness:

Let him be rich and weary, that at least,

If goodness lead him not, yet weariness

May toss him to my breast.

Oppenheimer is a fascinating figure, a man who brilliantly headed up the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos and then came to regret the bomb to such an extent that he was declared a security risk by Joseph McCarthy. His security clearance was taken away.

Oppenheimer was more than a brilliant mathematician and scientist. He was a Renaissance man, at one point learning Sanskrit and reading the Bhagavad Gita in the original. (This enabled him, after witnessing the first atomic explosion, to quote Krishna: “I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”) His was a restless intellect that never stopped.

That’s why he would have been drawn to the restless Herbert. “The Pulley” is a poem about what it takes to “pull” us to God. The nature of the device indicates that we must descend to rise. Herbert grasps God’s generous gifts to humans but can’t understand why appreciation for these gifts doesn’t lead him to a deep thankfulness. He even seems to blame God for making him this way. Why has God given him a restless mind that obstructs his desire to open himself to God? Intellectually he knows what he should do, but he can’t surrender. I sense that he feels like a bird beating itself against a mental cage. In another poem, “The Collar,” he even describes himself as raving and growing fierce and wild.

“The Pulley,” however, gives him a final consolation. Maybe he will wear himself out so much that he will fall at last, exhausted, into God’s arms. Maybe then he will find “the peace that passeth all understanding,” to quote from the Anglican liturgy. If he can’t find peace through his strength, beauty, wisdom, and honor, perhaps he will arrive there through fatigue.

The gifted Oppenheimer seems to have understood the struggle. He knew that his brilliance was not leading him to inner peace. Perhaps he appreciated Herbert for voicing his condition and was soothed by the poet’s vision of final rest.

2 Trackbacks

[…] word she picked up from her favorite George Herbert poem, “The Pulley.” I mentioned to her that this was also the favorite poem of Robert Oppenheimer, who famously pushed scientific knowledge in a Satanic direction through his supervision of the […]

[…] “The Pulley,” which I’ve written about here and mentioned here, Herbert describes restlessness as intrinsic to the human condition, and it […]