Monday

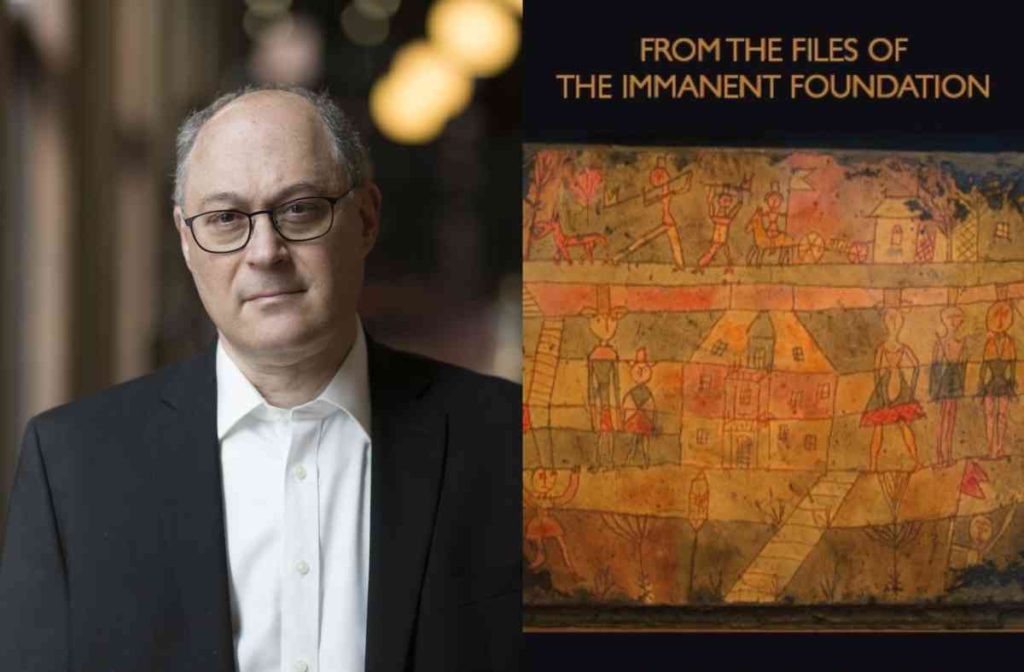

I’m currently writing a review of Norman Finkelstein’s poetry collection From the Files of the Immanent Foundation. As I noted in a recent post, Finkelstein, my best friend in graduate school, is a “New Gnostic” who uses poetry to get in touch with the numinous, the world of spirit.

Reviewing the work has proven more time-consuming than I anticipated, in part because I have had to track down the work’s many allusions, which in turn has sent me into unfamiliar works and subject areas. Suddenly I have found myself reading forgotten 19th century fantasy novels, accounts of secret societies, histories of alchemy and Gnosticism, and Aleister Crowley’s Magick in Theory and Practice (1929). In other words, Finkelstein writes the kind of poetry that one must read with a search engine in hand.

Fortunately, the side paths are fascinating enough to make the effort worthwhile. Given my own interest in fantasy literature, I am particularly intrigued by Finkelstein’s view that such literature provides glimpses into the supernatural. Even though the literature itself is fictional, Finkelstein believes that the authors sense something that is actually there, which they symbolically articulate through their stories and poems.

Among the fantasy works he alludes to are Arthur Machen’s White People, Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market, H. P. Lovecraft’s “The Dunwich Horror,” John Crowley’s Little, Big or the Faeries’ Parliament, Robert Browning’s Childe Harold to the Dark Tower Came, perhaps George MacDonald’s Princess and the Goblin, and Kenneth Graham’s Wind in the Willows. Here’s a glimpse of divinity as it occurs in Graham’s work, along with the drama of the poet who tries to capture it.

In the episode, Rat and Mole have a momentary encounter with the great god Pan:

`This is the place of my song-dream, the place the music played to me,’ whispered the Rat, as if in a trance. `Here, in this holy place, here if anywhere, surely we shall find Him!’

Then suddenly the Mole felt a great Awe fall upon him, an awe that turned his muscles to water, bowed his head, and rooted his feet to the ground. It was no panic terror — indeed he felt wonderfully at peace and happy — but it was an awe that smote and held him and, without seeing, he knew it could only mean that some august Presence was very, very near.

Following this encounter, however, Pan provides the animals with “the gift of forgetfulness.” As Graham explains it, this is “the last best gift that the kindly demi-god is careful to bestow on those to whom he has revealed himself in their helping.” That’s because, without forgetfulness,

the awful remembrance should remain and grow, and overshadow mirth and pleasure, and the great haunting memory should spoil all the after-lives of little animals helped out of difficulties, in order that they should be happy and lighthearted as before.

As a poet, however, Rat senses what they have experienced and turns to poetry to recover it. Listening to “the wind playing in the reeds,” he says it reminds him of

[d]ance-music—the lilting sort that runs on without a stop—but with words in it, too—it passes into words and out of them again—I catch them at intervals—then it is dance-music once more, and then nothing but the reeds’ soft thin whispering.’

Or as Finkelstein says about the numinous in “Sentences,”

Suppose it is neither terror

nor delight, but a perpetual rhythm, undulant

insistent, like a lost melody in the sound of a stream...

In yesterday’s post, I quoted from Alex Owen’s The Place of Enchantment that poetry’s “non-discursive representation of intuited reality” is necessary to express—or at least to approach expressing—encounters with divinity. Fiction, being more discursive, doesn’t get us as far. For instance, Pan doesn’t seem quite as mystical once he is spelled out.

Rat comes closer to the nature of divinity when the reeds provide him fragments of a poem. Before he can get the exact articulation, however, he falls asleep. Revelation only occurs at the edge of dreams.

Finkelstein, however, tries to combine the discursive explicitness of story with the intuition of poetry. Immanent Foundation feels like a story, although whether it’s fantasy, science fiction, or adventure is not clear. In a process he calls “code switching,” Finkelstein refuses to settle on any genre, which means that we have to respond to the associations that are evoked by each as it arises.

At the narrative center of these associations is the mysterious Foundation. “Immanent” means “infused with spirit” while “foundation” has multiple meanings that I’ll explore in a moment. Think of it for a moment as a think tank or a research institute that offers its students or members the opportunity to visit other realms.

To be sure, this is an oxymoron since something as solid and institutional as a foundation seems to have little in common with the spirit world of faerie and the imagination. Graham’s Rat would never visit a foundation, and in the poem “Shard” Finkelstein opines that “the true Foundation” should be “built upon air.”

Nevertheless, as soon as humans gather together in some joint enterprise, even one as ethereal as exploring the numinous, institutionalization becomes a fact of life. In an early poem, we see the Foundation promising to teach workshop participants how to penetrate the division between realms. In another poem, we see a parody of an academic conference, with the Foundation offering lectures on “The Medium and the Horse: Occupying Spectral Interiorities,” “Ectoplasm and the New Formularies: What We Need to Know,” and “Our Chakras, Ourselves: Forty Years of Microcosmic Pathfinding (book signing to follow).”

If Immanent Foundation is a fantasy story, then people have journeyed there to acquire occult powers. In one poem, they are told they will be taught stealth, diminution, possession, and embodiment.

However, while one can imagine these as invisibility, size reduction, etc., they can also be interpreted as skills valued by poets. Diminution would be authors who seek to diminish themselves so that the spirit can possess them, embodying itself in images and stories:

You have come to acquire

certain skills, acquaint yourself with certain

technologies, refine your powers of stealth

and diminution, possession and embodiment.

The rhetoric becomes magic as soon as you arrive.

It is possible to read the entire collection as a reflection upon the poetic process. By putting the Foundation at the center of his narrative, Finkelstein can imagine poets as different employees—for instance, as the gardener of the grounds, as an accountant who deals with numbers, as a translator, as a scribe, as a sensitive. When these figures carry out actions characteristic of those identities, we get different symbolic accounts of poetry.

The Foundation sometimes helps the poetic process and sometimes hinders it. (The same can be said of creative writing programs.) Certainly the visitor’s early optimism wears off as the poems progress, with tales of bureaucratic infighting and intransigent boards of directors. Elsewhere (in Ratio of Reason to Magic: New and Selected Poems) Finkelstein enigmatically explains that the Foundation “is not a governmental agency, not a sect or cult, not a fraternal organization, not a think tank, not a research institution—but I think it ‘exists’ in the space between and behind all such entities.”

Let’s look at some of these possibilities. As a think tank or research institution, it might bear resemblance to Edgar Cayce’s Association for Reason and Enlightenment, the Institute for Noetic Sciences, or Duke University’s Parapsychology Laboratory. At one time or another, governmental agencies such as the CIA, the FBI, and the Air Force have studied paranormal activity. And of course, there have always been secret societies and fraternal organizations devoted to the occult.

One of the more famous is the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, which attracted W. B. Yeats amongst others. Scholar Alex Owen, in The Place of Enchantment, examines the explosion of such groups in the 19th century, when many people were dissatisfied with organized religion but felt that there was more to life than industrial capitalism and the scientific method.

The Foundation refuses to be clearly defined, however. At one point it looks like a country estate, although one that has mysterious laboratories; a library where “the scholars sleepwalk forever and the catalogers despair”; a deconsecrated chapel where, “on certain days the choir is strewn with hay, on certain days with rushes,/ on certain days with ivy or with sand”; and a labyrinth featuring faded images from the Psychomachia, a medieval allegory. Regarding the laboratories, sometimes they feature older technology (pneumatic tubes, alembics, Kirlian photography for picking up auras), sometimes cyber technology from our own age (downloads, infected files). At one point, we encounter Emma, a “sensitive,” hooked up to electrodes.

The Foundation might also be the institution of literature itself, with generations of practitioners looking to their literary forebearers (found in the archives) for how to connect with the numinous. Or maybe the Foundation is no more than the imaginings of a crazed poet.

The collection as a whole is divided into four parts and an epilogue. In the first (“Margaret Resigns, & Other Rumors”), we are introduced to the Foundation and some of its employees. Margaret, at one point a muse figure designed to aid workshop participants, appears to become disenchanted with the Foundation and goes rogue (or something). The section ends with the gardener expressing his disillusion and climbing away on invisible stairs.

In the second (“The Dellschau Episode”) we learn about Charles Dellschau, a 19th century outsider artist who, after suffering a series of unimaginable personal losses, poured his grief into his art and drew thousands of visionary airships, some of which now sell for thousands of dollars. (You can read about him here.) Dellschau may have been a member of the “Sonora Flying Club,” which may or may not have existed during the California Gold Rush, but in any case Finkelstein recognizes in Dellschau’s dreams of flight his own longing for transcendence. He imagines Dellschau writing a journal entry that concludes:

Look how the rotors turn! New York Mechanical Zephyr Association? No, my friends—these are winds from the stars.

An anonymous member of the Foundation recognizes in Dellschau a kindred soul. Referring to the town dump where Dellschau’s drawings were headed before being rescued by a collector, he explains,

Testing the limits of his need,

he opens a portal to another dimension,

accommodating alien geometries through

his bravura designs. An Americana of the skies!

And his dreams, blooming from his memories;

his memories, unfolding from his dreams:

What, finally, could we make of these images,

these bittersweet derivatives, rescued at the last

instant from the town dump. Had we acted

in time, he could have found a home among us.

Yet even now, he is part of our secret history.

Part III (“Code Name: Emma”) features a woman who has an ambiguous relationship with both the Foundation and the speaker. Is she a “sensitive” that the Foundation studies (and spies upon) to make contact with the numinous? Is she a character in a horror movie who thinks of herself as autonomous, only to discover that her reality has been controlled by attached electrodes. Or is she a rogue actor who rebels against the Foundation as she tries to find her own way in the world. Once again, the narrative is suggestive without pinning anything down.

The “Lucy” in the final “Lucy Rescued” section (is she Narnia’s Lucy?) appears to be a poetic muse who has been kidnapped, thereby depriving the poet of connection with the spirit world (poetic inspiration). Without her, poetry is in danger of becoming just one damn sentence after another:

Suppose you are condemned to write sentences forever, sentences announcing that this one comes, followed by that one, until the place or the page is full.

And further on:

Then you think she is really gone, held captive, mute, spellbound, dancing interminably in a mindless round. The joyless pleasure of her deathless captors is the same pleasure they take in your sentencing, the same impossible task…

By the end, however, the narrator appears to have reconnected with Lucy, as well as with Margaret, Emma, and his own Judaic faith. There is a marriage and the poet imagines sailing off with Lucy in one of Dellschau’s flying machines. They’ve experienced hard times and doubts, but the fantasies have been proved to be real, even if only momentary and the product of dreams:

And yet they have gone out and returned with hardly any support. Across perilous seas, through founding fires, entombed in earth, and opposed by the monarchs of the air, their fantasies hold true, even as they watch them dissolve. He blinks. It’s all good.

Immanent Foundation concludes with a five-poem epilogue in which the narrator reflects upon the enterprise. There are allusions to the early Melies film Voyage to the Moon, with its fantastical dreams of flight; a love poem dedicated to the poet’s wife (“in your wish to fly, flight/ will take you where you want to go”); a reflection upon the power of simple symbols; and a sign-off in which, describing himself as an accountant, he “snoozes at his desk” and thinks of all that his poetic project has created. The image may be drawn from the Chinese fairy tale “Cloak of Dreams”:

In his dream, he sees the Lord of Dreams. He sees himself and all the others, “the living and the dead, and one by one they vanish into the darkness of his cloak.”

If you like your poetry clearly set forth, you will find Immanent Foundation to be frustrating. If you just flow with the images, however—even without the use of a search engine—you’ll understand enough to intrigue you and tickle your imagination. After that, the question becomes how deep you want to go.