Sports Saturday

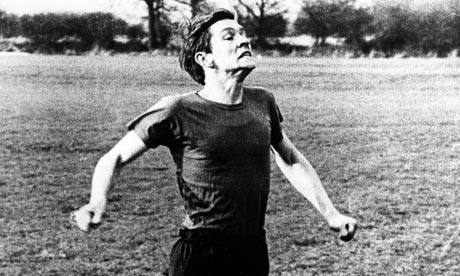

It’s perfect jogging weather in Maryland at the moment (sunny with the temperature in the 50’s) so I share with you a passage from Alan Sillitoe’s Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, one of the great stories about running. Colin, the narrator, is in a reform school for boys (Borstal) for having stolen a cashbox. When the headmaster discovers that he has a talent for running, he gives him special privileges so that he will be able to represent the school in its contest with a fancy private school.

Colin is torn because he feels he has sold out. To prove to himself that he hasn’t, he plans to throw the race at the last minute, thereby dashing the headmaster’s dreams. Much of the story involves an interior dialogue during the race that takes him into some areas that he doesn’t want to visit. Note the drama of attempting to suppress thoughts that insist upon being heard:

Gunthorpe [his main competitor] nearly caught me up. Birds were singing from the briar hedge, and a couple of thrushies flew like lightning into some thorny bushes. Corn had grown high in the next field and would be cut down soon with scythes and mower; but I never wanted to notice much while running in case it put me off my stroke, so by the haystack I decided to leave it all behind and put on such a spurt, in spite of nails in my guts, that before long I’d left both Gunthorpe and the birds a good way off; I wasn’t far now from going into that last mile and a half like a knife through margarine, but the quietness I suddenly trotted into between two pickets was like opening my eyes underwater and looking at the pebbles on a stream bottom, reminding me again of going back that morning to the house in which my own man had croaked, which is funny because I hadn’t thought about it at all since it happened and even then I didn’t brood much on it. I wonder why? I suppose that since I started to think on these long-distance runs I’m liable to have anything crop up and pester at my tripes and innards, and now that I see my bloody dad behind each grass-blade in my barmy runner-brain I’m not so sure I like to think and that it’s such a good thing after all. I choke my phlegm and keep on running anyway and curse the Borstal-builders and their athletics—flappity-flap, slop-slop, crunchslap-crunchslap-crunchslap—who’ve maybe got their own back on me from the bright beginning by sliding magic-lantern slides into my head that never stood a chance before. Only if I take whatever comes like this in my runner’s stride can I keep on keeping on like m old self and beat them back; and now I’ve thought on this far I know I’ll win, in the crunchslap end. So anyway after a bit I went upstairs one step at a time not thinking anything about how I should find dad and what I’d do when I did. But now I’m making up for it by going over the rotten life mam led him ever since I can remember, knocking-on with different men even when he was alive and fit and she not caring whether he knew it or not, and most of the time he wasn’t so blind as she thought and cursed and roared and threatened to punch her tab, and I had to stand up to stop him even though I knew she deserved it. What a life for all of us. Well, I’m not grumbling, because if I did I might just as well win this bleeding race, which I’m not going to do, though if I don’t lose speed I’ll win it before I know where I am, and then where would I be?

This attack on post World War II social conditions by one of Britain’s “angry young men” contains a contradictory mixture of hope (a young man makes what feels to him a principled stand) and despair (his time in the school only turns him into a more effective thief). But running at least helps him get in touch with some of his pain.