Thursday

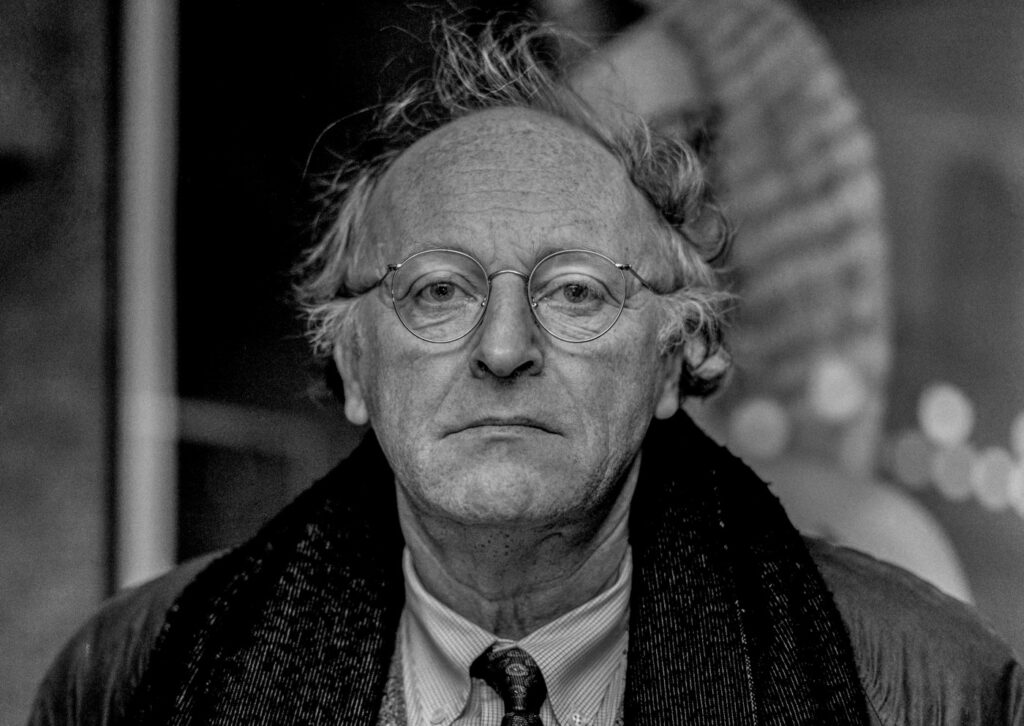

Yesterday’s post on Russia’s refusal to acknowledge Ukraine as its own country discussed poetry’s role in nation formation. In a lengthy twitter thread, scholar Kamil Galeev alerted me to a poem by Joseph Brodsky, Soviet émigré and Nobel Prize winner, that expresses Russia’s refusal. The poem shows me the depth of Russian sentiment better than anything else I have seen.

In fact, Galeev’s twitter thread and Brodsky’s poem make me realize that we must attribute the invasion to Russia as well as to Putin. We in the west have wanted to believe that Putin was misleading his country about Ukraine as a security threat. If only Russians would realize there is no threat, we’ve been thinking, they would oppose the invasion. I now realize that Putin’s hostility to Ukrainian independence predates him and has a long history.

Brodsky wrote his poem in 1991, when the Soviet Union was breaking up and the former “soviet socialist republics” wanted to become their own nations. To capture the distress that Russia felt over “losing” Ukraine, Brodsky imagines Russia as a jilted lover venting his fury. Below I cover the general message and tenor of “On Ukrainian Independence,” but if you want a full annotation of the poem, you can go here.

The poem begins with a reference to a famous 1709 battle in which Russia defeated Sweden’s invasion of Ukraine. It’s a moment of Russia-Ukraine lovemaking that the speaker remembers fondly. If Ukraine now wants to break up, the desire must come from elsewhere: say, from anarchists with their green flag or nationalistic ex-patriates living in Canada. As a sign of their former affection, the poet playfully uses ethnic slurs in his exchange: “Khokhly” for Ukrainians, “Katsapy” for Russians. He dreams of the good times (embroidered Ukrainian towels, sunflowers) and acknowledges some Russian responsibility for the break-up: “We Katsapy have no right to charge them with treason./ With icons and vodka, for seventy years we’ve bungled,/ In our Ryazan we’ve lived like Tarzan in the jungle.” Which is to say, “Since the Russian Revolution, we Russians have lived in a primitive state (icons, vodka, uncultured backwater), so I can see why you might want to leave us.”

So, like a man putting on a brave face as his mistress drops him, he tries to wish her well:

Away with you, Khokhly, and may your journey be calm!

Wear your zhupans [traditional garb], or uniforms, which is even better,

Go to all four points of the compass and all the four letters.

Then the bitterness simmering beneath the surface comes pouring out, filled with World War II references. Go back to your primitive “huts,” he tells Ukraine, where you can expect to be gang-banged by “Krauts and Polacks.” After all, you no longer have me to protect you. It was nice, he says, “hanging together from the same gallows loop” (the reference here is to Nazi slaughter of Russians and Ukrainians together), but now the beetroot soup we used to share you can eat all by yourself. Oh, and “good riddance.”

His thoughts turn to the Dnieper River, which flows from Russia to and through Ukraine, and he imagines it flowing in reverse. This in turn causes him to imagine two trains passing. Ukraine is a bullet train, speeding into the future and “looking askance” as it nurses its “age-old grievance.” I’m not sure what spitting into the river signifies. Maybe a symbolic letting go?

Except that this lover can’t let go. The more he claims that he’s so over her, the less convincing he sounds:

Don’t speak ill of us. Your bread and wheat we don’t need,

Nor your sky, may we all choke on sunflower seed.

No need for bad blood or gestures of fury ham-fisted,

Seems that our love is up, if it at all existed.

You’re not going to see me cry, he declares:

Oh, gardens and grasslands and steppes, dumplings filled with honey!

We’ve had greater losses before, lost more people than money.

We’ll get by somehow. And if you want teary eyes –

Wait ‘til next time, guys, this provision no longer applies.

Finally, characterizing Ukrainians as murderous fascists, he unloads with one final revenge fantasy. When his ex is on her deathbed, he informs her, she’ll regret her decision. How so? She’ll remember lines from Pushkin, not from Ukraine’s national poet:

God rest ye merry Cossacks, hetmans, and gulag guards!

But mark: when it’s your turn to be dragged to graveyards,

You’ll whisper and wheeze, your deathbed mattress a-pushing,

Not Shevchenko’s bullshit but poetry lines from Pushkin.

Here’s the poem in its entirety:

On Ukrainian Independence

Dear Charles XII, the Poltava battle [1]

Has been fortunately lost. To quote Lenin’s burring rattle,

“Time will show you Kuzka’s mother,” ruins along the waste,

Bones of post-mortem bliss with a Ukrainian aftertaste.It’s not the green flag, eaten by the isotope,

It’s the yellow-and-blue flying over Konotop,

Made out of canvas – must be a gift from Toronto–

Alas, it bears no cross, but the Khokhly don’t want to.Oh, rushnyks and roubles, sunflowers in summer season!

We Katsapy have no right to charge them with treason.

With icons and vodka, for seventy years we’ve bungled,

In our Ryazan we’ve lived like Tarzan in the jungle.We’ll tell them, filling the pause with a loud “your mom”:

Away with you, Khokhly, and may your journey be calm!

Wear your zhupans [traditional garb], or uniforms, which is even better,

Go to all four points of the compass and all the four letters.It’s over now. Now hurry back to your huts

To be gang-banged by Krauts and Polacks right in your guts.

It’s been fun hanging together from the same gallows loop,

But when you’re alone, you can eat all that sweet beetroot soup.Good riddance, Khokhly, it’s over for better or worse,

I’ll go spit in the Dnieper, perhaps it’ll flow in reverse,

Like a proud bullet train looking at us askance,

Stuffed with leathery seats and ages-old grievance.Don’t speak ill of us. Your bread and wheat we don’t need,

Nor your sky, may we all choke on sunflower seed.

No need for bad blood or gestures of fury ham-fisted,

Seems that our love is up, if it at all existed.Why should we plow our broken roots with our verbs?

You were born out of earth, its podzolic soils and its herbs.

Quit flexing your rights and laying all the blame on us,

It is your bloody soil that has become your onus.Oh, gardens and grasslands and steppes, varenyks filled with honey!

We’ve had greater losses before, lost more people than money.

We’ll get by somehow. And if you want teary eyes –

Wait ‘til next time, guys, this provision no longer applies.God rest ye merry Cossacks, hetmans, and gulag guards!

But mark: when it’s your turn to be dragged to graveyards,

You’ll whisper and wheeze, your deathbed mattress a-pushing,

Not Shevchenko’s bullshit but poetry lines from Pushkin.

In his twitter commentary on the poem, Galeev writes that

Brodsky sends multiple messages to Ukrainians (called with slur “Khokhly”). He: 1. Tells Ukrainians to go fuck themselves 2. Predicts: “you, scum will be gangbanged by Poles and Germans” 3. Wonders if he should spit in Dnieper in order to make it flow backwards.

Noting that Brodsky called the poem “risky,” Galeev argues that it

correctly reflected attitude of much of Russian society towards Ukraine. After 2014 it became especially relevant and was repeatedly endorsed by the media and authorities like the Russian parliament newspaper.

While I think that Galeev is right about the depth of Russian anger, I think he misses Brodsky’s comic irony. After all, one doesn’t go to a jilted lover for an objective assessment of a breakup. The feelings expressed, especially imagining an unprotected Ukraine raped, are not politically correct, but when are broken-hearted lovers ever politically correct? What I see in the poem is deep grief over the break-up between Russia and Ukraine. They’ve had a long history together and now it’s over.

But in an ironic twist of unspeakable horror, Ukrainian women are indeed being gangbanged because of the separation—only the rapists are not Germans or Poles but Russians. It’s as though the jilted lover, after having vented his grief through revenge fantasies, has become a murderous stalker prepared to enact them in real life.

That Russian media has missed the irony and is quoting the poem to cheer on the stalker—well, that is what we’ve come to expect of the state-owned Russian media. Galeev believes that Russia’s fury over Ukraine is so unhinged that he expects it to resort to tactical nuclear weapons if it can’t hold on to her.

If Brodsky saw this poem as risky in 1991, he would see it even more so now. What his poem shows me is what Galeev has been saying: that the Russian sense of connection with Ukraine is profound and existential. Brodsky, as a former Russian, may well grieve the separation and I imagine that he thinks Ukraine has made a mistake. After all, it has traded Pushkin for Shevchenko. But unlike Putin, Brodsky finds, in poetry, a healthy way to express his grief.