Wednesday

My eight-year-old grandson Alban has fallen in love with T.S. Eliot’s cat poems. “Mungojerrie and Rumpleteazer” is his current favorite, followed by “Old Gumbie Cat,” “Macavity,” and “Jellico Cats.” Each day I introduce him to a new one, and we’re about halfway through Eliot’s collection.

It came about from teaching him Language Arts during the school year. Because his parents are so busy, with my son in charge of &Pizza’s technology and my daughter-in-law running the Children’s Choir of Washington, they farmed out Alban’s on-line learning to the four grandparents.

For a while I dutifully taught Alban about climate change and had him writing diaries, opinion pieces, and other genres. (Somehow every piece involved exciting escapes. Alban created a character who reports on Bangladesh floods, California wildfires, Central American mudslides.) Then the school gave us permission to teach whatever we wanted, at which point I switched to teach poetry.

Alban, who plays the violin, has a great ear for poetic rhythm. When he reads aloud, he instinctively figures out where the stresses go and rereads lines to make them fit. For a while, I chose particularly bouncy poetry.

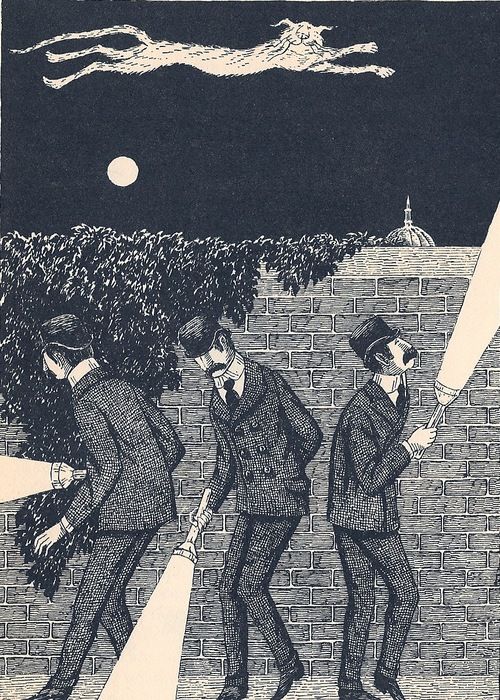

“Macavity” is one of the bounciest of Eliot’s cat poems, with stanzas like the following:

Macavity, Macavity, there’s no one like Macavity,

For he’s a fiend in feline shape, a monster of depravity.

You may meet him in a by-street, you may see him in the square—

But when a crime’s discovered, then Macavity’s not there!

While Alban liked this, he soon discovered, pleasure can be gained from varying the rhythm. He figured out that Gumbie Cat has one rhythm for her day time activities and another for her nighttime activities, which are described in alternating stanzas.

He also figured out, as I had not, why there’s a significant rhythm shift in “Mr. Mistoffelees,” the “original conjuring cat.” The poem begins with tortured rhymes and rhythms but then—with a “presto”—it moves into a different key. When Alban compared it to a magician waving a wand, I could only gape in admiration. Here’s the first stanza and a bit of the second:

You ought to know Mr. Mistoffelees! The Original Conjuring Cat— (There can be no doubt about that). Please listen to me and don’t scoff. All his Inventions are off his own bat. There’s no such Cat in the metropolis; He holds all the patent monopolies For performing surprising illusions And creating eccentric confusions. At prestidigitation And at legerdemain He’ll defy examination And deceive you again. The greatest magicians have something to learn From Mr. Mistoffelees’ Conjuring Turn. Presto! Away we go! And we all say: OH! Well I never! Was there ever A Cat so clever As Magical Mr. Mistoffelees! He is quiet and small, he is black From his ears to the tip of his tail; He can creep through the tiniest crack He can walk on the narrowest rail.

As I listen to him read, I note Eliot’s allusions: Mistoffelees is inspired by Marlowe’s Mephistophilis, Growltiger by Barrie’s Captain Hook, Macavity by Doyle’s Moriarty, Jellico Cat by the blackface minstrel song “Buffalo Gals.”

Alban is also hungry for poetic terms to describe the reading experience, such as half rhyme, simile, alliteration, couplet, rhyme scheme, and the like. He picks them up the way that he once learned the complicated names of dinosaurs and with the same enthusiasm

We’re working our way through Louis Untermeyer’s Golden Treasury of Poetry, which has catchy illustrations and which I loved as a child. When he reads a poem that doesn’t appeal to him, he shrugs and moves on.

Sometimes we’ll imagine the poems talking to each other. Who would prevail between the Edward Anthony’s “Bloodhound” (“Folks either must avoid temptation/Or face my nasal accusation”) and Macavity? Clearly Macavity, Alban says. He loves riddle poems, such as “Enigma on the Letter H” where “H” is answer to all the poem’s queries (“…though deaf to the ear,/ It will make it acutely and instantly hear”). He enjoyed the explanation, in W.S. Gilbert’s “The Yarn of the Nancy Bell,” for how an elderly naval man can be, all at once,

…a cook and a captain bold,

And the mate of the Nancy brig,

And a bo’sun tight, and a midshipmite,

And the crew of the captain’s gig.

The answer: The men were shipwrecked and had to resort to cannibalizing each other.

Alban also finds hilarious James Thomas Fields’ “The Owl-Critic,” in which a man in a barber shop critiques an apparently stuffed owl, only to have the owl fly off after seeming to say,

“Your learning’s at fault this time, anyway;

Don’t waste it again on a live bird, I pray.

I’m an owl; you’re another. Sir Critic, good day!”

And the barber kept on shaving.After the school year ended, Alban wanted to keep going so it appears our time together will last through the summer. Given the uncertainties of the coronavirus, perhaps longer.