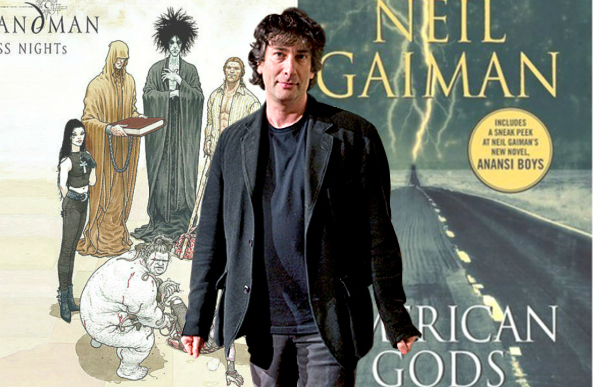

Yesterday I wrote about how, in American Gods, fantasist Neil Gaiman detects a thirst for violence within the American psyche. His book ends with a victory over bloody paroxysms, however. The question is whether the ending is itself just a fantasy or whether it is a viable model for action. Does Gaiman provide genuine insight into how to save the American republic?

As I see it, through his protagonist he shows us that we should face up to our fears and evasions, turn our back on shallow wish fulfillments, and follow our higher instincts, which may take the form of mythic guides. These guides can can come from our various faith and folk traditions:

Religions are, by definition, metaphors, after all: God is a dream, a hope, a woman, an ironist, a father, a city, a house of many rooms, a watchmaker who left his prize chronometer in the desert, someone who loves you…

Among Gaiman’s gods are American legends, who arose because they fed some deep need. Johnny Appleseed and Paul Bunyan make appearances.

Gaiman cautions, however, that one must listen to these guides intelligently and with full awareness. Don’t be pulled in by blind devotion because abdication of personal responsibility only leads to more violence.

“Shadow” is so called because he follows the lead of others, a shadow. If, in Yeats’ famous poem (which Gaiman quotes), the worst are filled with passionate intensity while the best lack all conviction, Shadow is among the best. The ghost of his dead girlfriend tells him he is not truly alive, but at least he is a sympathetic soul who has integrity and cares for others. In other words, he, like America, has potential, even though he also has a lot of work to do.

For a while, he is reactive rather than proactive. As the chauffeur of the Norse god Odin, he simply does what he is told. For a few months he lives a routine existence in an idyllic 1950s-style town where everything seems to be perfect.

None of this, however, is truly living, and there are many signs of trouble. As I noted yesterday, one source of America’s violence may be a disconnect between deep spiritual longing and the materialistic culture upon which it has to operate. People seek out places that seem to be vaguely spiritual—say, Rock City or Mount Rushmore—and leave dissatisfied. They want to find something to believe in and come up empty.

The hunger seems related to identity confusion. Odin at one point observes that America

is the only country in the world that worries about what it is…The rest of them know what they are. No one needs to go dsearching for the heart of Norway. Or looks for the soul of Mozambique. They know what they are.

The longing for certainty and stability can lead to devil’s bargains. In the case of the ideal town, their gated existence relies on sacrificing a young person each year. It is a version of what we ourselves do when we send young people off to war to protect us or sacrifice their future for our present convenience.

I’ve seen the identity confusion and the spiritual hunger in my students. It was particularly evident following the attacks of 9-11, when many felt that they knew who they were and what their lives meant for the first time. I saw it again during Barack Obama’s 2008 run for the presidency, when genuine participatory democracy seemed possible again. But the newly discovered idealism of 9-11 patriots was cynically exploited to launch the disastrous invasion of Iraq, and the poetry of Obama’s “hope and change” slid inevitably into the prose of actually governing. When the glow wears off, people find themselves thrown again into doubt.

Gaiman advises us to take full stock of our existence and then venture out without illusion and without thinking that we have control. After his boss dies, Shadow decides that he will stop drifting and will instead undertake an extreme vigil, somewhat like a Native American vision quest. He wants to learn what there is to learn from being tested.

He gets the message that, if he is to find meaning in the world, it is up to him to make it. Neither fidelity to the old gods nor submission to consumer capitalism can offer him anything worthwhile. America is bigger than our conceptions of it and all we can do is make our way to the best of our abilities. As Shadow tells the contending forces of old gods and modernity,

You know, I think I would rather be a man than a god. We don’t need anyone to believe in us. We just keep going anyhow. It’s what we do.

And as he himself is told by “the buffalo man,” a Native American spirit who stands in for “the land,”

You did well… You made peace. You took our words and made them your own.

There’s still a lot about Gaiman’s book that I don’t understand but he seems to be saying that Americans will always be in search, always dreaming. We can never know ultimately who we are, which makes the road novel the quintessential American genre.

Our challenge is to be at peace with this lack of certainty. Some freak out and become destructive whenever they encounter ambiguity. They believe they must force themselves and others into one mold.

They should consider instead Shadow’s final gesture, which points towards infinite possibility because Shadow is okay with an indefinite and an unknown future:

He tossed the [gold] coin into the air with a flick of his thumb.

It spun golden at the top of its arc, in the sunlight, and it glittered and glinted and hung there in the midsummer sky as if it was never going to come down. Maybe it never would. Shadow didn’t wait to see. He walked away and he kept on walking.