High school English teachers sometimes have to remind themselves that Shakespeare wasn’t targeting adolescents in his plays, and college English teachers similarly need to shake free of early adulthood framework that begins to define the works that they teach. It’s an occupational liability that we encounter.

This was the subject of a conversation I had this past December with my 32-year-old son Darien and with John Grammer, who runs the University of the South’s School of Letters each summer in Sewanee, Tennessee. Darien talked about how reading Moby Dick after spending several years in the world of business made the novel a far richer experience than it would have been had he encountered it in college.

Reading the novel on the New York subway, Darien was very attuned to Pequod’s hierarchy, which was not unlike that of an advertising firm he had once worked at. He loved the images of the men working together with urgency and a sense of common purpose. He was also attuned to how bad management can run an enterprise off the rails. The Quaker investors who are financing Captain Ahab would be more than a little concerned if they knew about his obsession. One hopes they are insured.

John talked about how wonderful it was teaching adults in the Institue of Letters. Many of them are high school teachers, who prize the chance to explore literature with other adults before returning to the classroom. Sewanee sits 2000 feet up atop a plateau, making it an idea place to read and discuss.

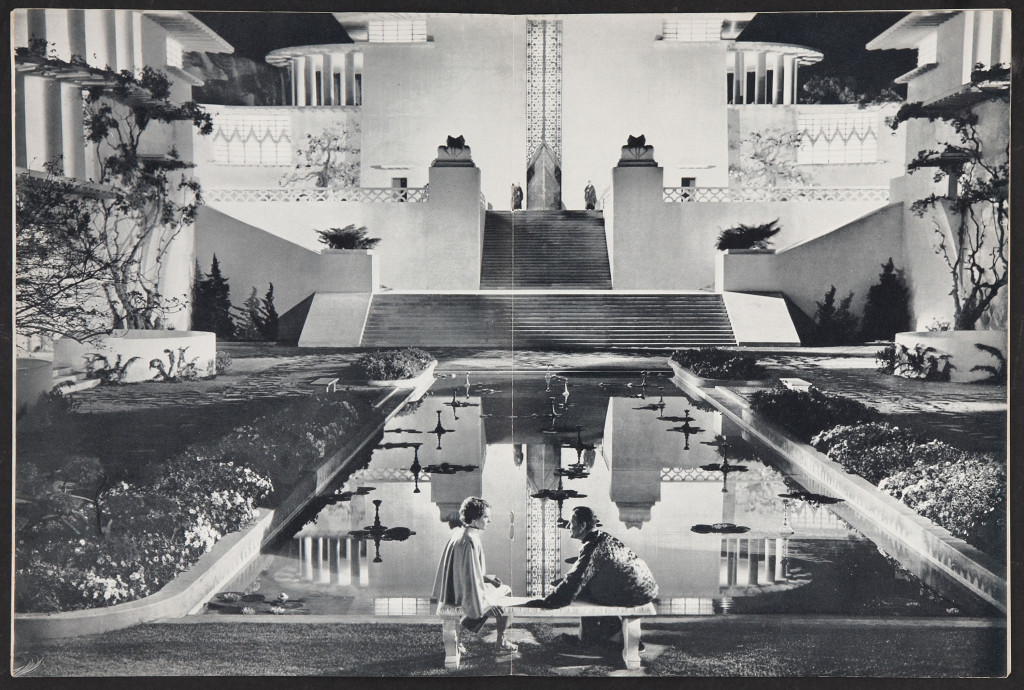

Thinking about John’s institute, I was put in mind of James Hilton’s description of Shangri-La in Lost Horizon, also perched high in the hills. One could do worse than model a school on the monastery that Conway encounters there:

He did not think he had ever been so happy, even in the years of his life before the great barrier of the war. He liked the serene world that Shangri-La offered him, pacified rather than dominated by its single tremendous idea. He liked the prevalent mood in which feelings were sheathed in thoughts, and thoughts softened into felicity by their transference into language. Conway, whom experience had taught that rudeness is by no means a guarantee of good faith, was even less inclined to regard a well-turned phrase as a proof of insincerity. He liked the mannered, leisurely atmosphere in which talk was an accomplishment, not a mere habit. And he liked to realize that the idlest things could now be freed from the curse of time-wasting, and the frailest dreams receive the welcome of the mind. Shangri-La was always tranquil, yet always a hive of unpursuing occupations; the lamas lived as if indeed they had time on their hands, but time that was scarcely a featherweight. Conway met no more of them, but he came gradually to realize the extent and variety of their employments; besides their knowledge of languages, some, it appeared, took to the full seas of learning in a manner that would have yielded big surprises to the Western world. Many were engaged in writing manuscript books of various kinds; one (Chang said) had made valuable researches into pure mathematics; another was coordinating Gibbon and Spengler into a vast thesis on the history of European civilization. But this kind of thing was not for them all, nor for any of them always; there were many tideless channels in which they dived in mere waywardness, retrieving, like Briac, fragments of old tunes, or like the English ex-curate, a new theory about Wuthering Heights. And there were even fainter impracticalities than these. Once, when Conway made some remark in this connection, the High Lama replied with a story of a Chinese artist in the third century B.C. who, having spent many years in carving dragons, birds, and horses upon a cherrystone, offered his finished work to a royal prince. The prince could see nothing in it at first except a mere stone, but the artist bade him “have a wall built, and make a window in it, and observe the stone through the window in the glory of the dawn.” The prince did so, and then perceived that the stone was indeed very beautiful. “Is not that a charming story, my dear Conway, and do you not think it teaches a very valuable lesson?”

Conway agreed; he found it pleasant to realize that the serene purpose of Shangri-La could embrace an infinitude of odd and apparently trivial employments, for he had always had a taste for such things himself. In fact, when he regarded his past, he saw it strewn with images of tasks too vagrant or too taxing ever to have been accomplished; but now they were all possible, even in a mood of idleness.

Having grown up in Sewanee, maybe it is nostalgia that causes me to think that time stops there as it does in Shangri-La. On the other hand, retreating from the world to bury oneself in books sounds idyllic to me. If you think you might be interested in John’s program, it runs this year from June 7-July 17.