Wednesday

This evening I’m giving a talk on angels as they appear in contemporary fantasy fiction so I’ll use today’s post for some initial brainstorming. The talk is the third of three on angels for Vacation Bible School, and, in the first, Dr. Becky Wright of Sewanee’s Theological Seminary informed us that the angels that show up in the Old and New Testaments are metaphorical rather than literal and were indeed seen that way. It was only in later years that they hardened into actual beings. Or, as we used to say when studying Marxist intellectual history at Carleton College, a once dynamic concept became reified, a shell of its former meaning.

Becky noted that translators always have to make a choice when they translate malakh (Hebrew) and angelos (Greek): both words mean both messenger and angel. Sometimes the translators choose one, sometimes the other, but in both cases we need to drop the notion of beautiful and androgynous beings with flowing locks showing up. After all, Becky pointed out, their first words are often, “Be not afraid,” and why should someone be afraid of a Hallmark card angel.

It’s more useful, she noted, to think of angels as metaphors for divine inspiration, similar to the way that Homer and the ancient Greeks personified creative inspiration as the muses. When one feels one has received a message, one searches for a way to visualize the experience and angels are one visualization.

Once Becky pointed this out, I felt right at home. After all, metaphors—or, to go broader, figurative language—are the meat and potatoes of literature, including contemporary fantasy. So what is the symbolic significance of angels in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy, Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman’s Good Omens, and China Mieville’s Perdito Street Station?

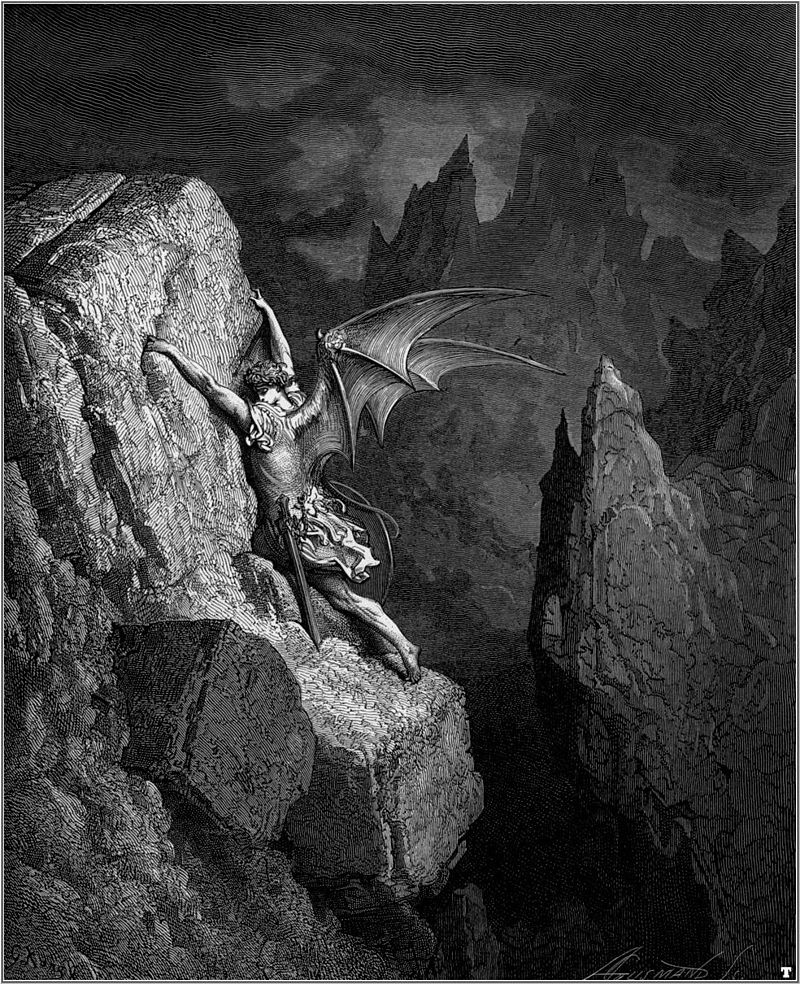

I’ll confine myself to Pullman for today’s post. The second talk in the series was my Sewanee colleague Ross Macdonald’s discussion of angels in Paradise Lost, and the poem is Pullman’s jumping off point. In fact, “his dark materials” is a line from the poem, a reference to the material that God uses to create worlds.

Pullman has a love-hate relationship with Milton, however, and ascribes to William Blake’s perspective that “Milton was of the devil’s party without knowing it.” In Pullman’s trilogy, then, he turns Milton on his head by making his fallen angels the good guys and the loyal angels the bad guys.

I find this to be a slightly shaky foundation for a story since, much as I admire Blake, I don’t agree with his view of Paradise Lost. As I see it, Satan is one of literature’s great depictions of a charismatic narcissist, and I think Milton intends for us to fall for his charisma before becoming aware of his emptiness. But set that aside. Pullman’s Satanic rebel is a couple, Lord Asriel and Mrs. Coulter, who go to war with God, his archangel Metatron, and his legions of angels. They have a few angels on their side, as well as witches and giant polar bears.

In Pullman’s version, God is not the actual creator but an angel who took credit for creation, which means that Pullman is not as radical as he appears. (In other words, “God” isn’t really God.) The author’s target is people who claim to speak in God’s name while twisting God to serve their own purposes. But if this is Pullman’s purpose, why not just go after the church rather than having this titanic battle in heaven, complete with flying machines and bombs.

For the record, Pullman targets the church plenty. The church we see in the trilogy is a cross between the Catholic Church of the Spanish Inquisition and the fundamentalist Protestant church of Calvin’s Geneva. Both are obsessed with purity and obedience, which means that they are prepared to do everything they can to keep children from thinking for themselves and from enjoying sexuality. They are fanatical opponents of sensuality.

The reason for the aerial battles is that Pullman wants his battle against intolerance and narrow-minded religiosity to be as spectacular as Milton’s battle in heaven. Pullman has said this His Dark Materials is his own Paradise Lost. But where Milton uses his poem to “justify the ways of God to man”—to find divine meaning to our suffering—Pullman wants us to focus on living our lives fully and sensually. He wants us to build the kingdom of heaven on earth—or to use phrase he uses, the republic of heaven.

We should not want to become angels, he notes, because they are ethereal. Pullman’s angels, rather than glorying in their immateriality, envy humans. As Mrs. Coulter notes when she is in the process of using her beauty to seduce Metatron into a trap where she and Asriel can destroy him,

[S]he trusted to her flesh, and to the strange truth she’d learned about angels, perhaps especially those angels who had once been human: lacking flesh, they coveted it and longed for contact with it. And Metatron was close now, close enough to smell the perfume of her hair and to gaze at the texture of her skin, close enough to touch her with scalding hands.

For those who think that Heaven is heavenly because it is purely ethereal, Pullman has a countervision. In his vision, Christian Heaven is a barren place, dark and empty. At one point, protagonists Lyra and Will find a way to release those trapped there—at least those who haven’t deluded themselves into thinking that their sense-starved existence is Paradise—and the dead souls are thrilled when they get a chance to mingle with the elements. Here’s Pullman describing the moment when they move from the afterlife to earth:

The first ghosts trembled with hope, and their excitement passed back like a ripple over the long line behind them, young children and aged parents alike looking up and head with delight and wonder as the first stars they had seen for centuries shone through into their poor starved eyes.

The first ghost to leave the world of the dead was Roger. He took a step forward and turned to look back at Lyra, and laughed in surprise as he found himself turning into the night, the starlight, the air…and then he was gone, leaving behind such a vivid little burst of happiness that Will was reminded of the bubbles in a glass of champagne.

As Robert Frost says, “Earth’s the right place for love, I don’t know where it’s likely to go better.”

If Lord Asriel and Mrs. Coulter are not able to defeat Metatron, then he will impose his will directly on the world rather than having to go through the church. In other words, we will have orthodoxy or fundamentalism on steroids. Some version of Margaret Atwood’s Gilead, in other words.

But because they take down Metatron, the next generation will be able to think for themselves and taste, without guilt, the forbidden fruit of sexuality. In fact, we see Lyra actually feeding Will a “little red fruit” in the lead-up to their lovemaking scene. Their love, which both the church and Metatron have been doing all they can to prevent, saves the world.

Hmm, love saving the world. Where else does one encounter that idea? Maybe Pullman isn’t as anti-Christian as he seems.