Friday

A recent NBC new story has captured, in a particularly effective way, the effect that Texas’s new book ban is having on young people. Often we talk about these book bans in an abstract way, but reporter Mike Hixenbaugh interviewed a 17-year-old queer student in the city of Katy about the impact on her personally:

From a secluded spot in her high school library, a 17-year-old girl spoke softly into her cellphone, worried that someone might overhear her say the things she’d hidden from her parents for years. They don’t know she’s queer, the student told a reporter, and given their past comments about homosexuality’s being a sin, she’s long feared they would learn her secret if they saw what she reads in the library.

That space, with its endless rows of books about characters from all sorts of backgrounds, has been her “safe haven,” she said — one of the few places where she feels completely free to be herself.

Hixenbaugh reports that some of the student’s favorite books “have been vanishing from the shelves of Katy Independent School District libraries the past few months”:

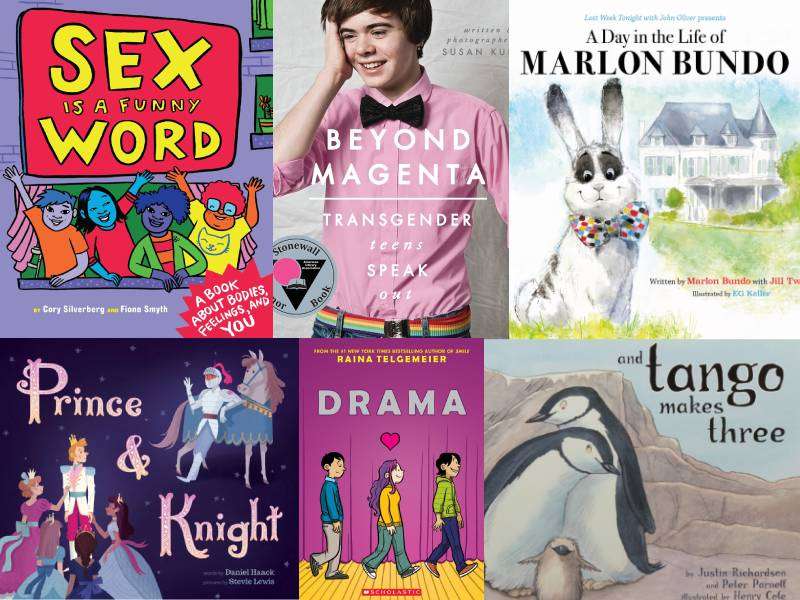

Gone: Jack of Hearts (and Other Parts), a book she’d read last year about a gay teenager who isn’t shy about discussing his adventurous sex life. Also banished: The Handsome Girl and Her Beautiful Boy, All Boys Aren’t Blue and Lawnboy — all coming-of-age stories that prominently feature LGBTQ characters and passages about sex. Some titles were removed after parents formally complained, but others were quietly banned by the district without official reviews.

The student told Hixenbaugh, “As I’ve struggled with my own identity as a queer person, it’s been really, really important to me that I have access to these books,” adding, “You should be able to see yourself reflected on the page.”

So what are parents afraid of? Do they think that, by reading such books, their straight children will become queer? Or do they want those of their children who are repressing “a certain tendency” (to use the euphemism used in Oscar Wilde’s trial”) to keep repressing it and fear they might stop doing so once they encounter these works.

Or here’s a third possibility, expressed by Vietnamese-American author Vien Thanh Nguyen, whom I wrote about yesterday. Sometimes such parents

see danger in empathy. This appeared to be the fear that led a Texas school district to cancel the appearance of the graphic novelist Jerry Craft and pull his books temporarily from library shelves last fall. In Mr. Craft’s Newbery Medal-winning book, New Kid, and its sequel, Black middle-schoolers navigate social and academic life at a private school where there are very few students of color. “The books don’t come out and say we want white children to feel like oppressors, but that is absolutely what they will do,” the parent who started the petition to cancel Mr. Craft’s event said. (Mr. Craft’s invitation for a virtual visit was rescheduled and his books were reinstated soon after.)

Examining the parent’s comments, Nguyen concludes that what makes the “sweet, shy, comics-loving” protagonist of New Kid so dangerous to white parents is his “relatability”:

The historian and law professor Annette Gordon-Reed argued on Twitter that parents who object to books such as New Kid “know their kids will do this instinctively. They don’t want to give them the opportunity to do that.”

Nguyen continues,

Those who ban books seem to want to circumscribe empathy, reserving it for a limited circle closer to the kind of people they perceive themselves to be. Against this narrowing of empathy, I believe in the possibility and necessity of expanding empathy — and the essential role that books such as New Kid play in that. If it’s possible to hate and fear those we have never met, then it’s possible to love those we have never met. Both options, hate and love, have political consequences, which is why some seek to expand our access to books and others to limit them.

If this is true, then parents of the queer teen interviewed by NBC may not only fear that their kids will come out after reading LGBTQ fiction and memoirs. It’s that they might start accepting them LGBTQ folk as fellow human beings rather than as abominations. They might leave their parents’ hatreds behind.

Grim as these book bans are, there are a few signs of hope. When I applied Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 to the situation last week (Nguyen also cites the work), I mentioned the old professor’s lament that he did not do more to stand up against the book censors. It so happens that book lovers have started fighting back against rightwing ban efforts. Another NBC story reports the efforts in another Texas community, Round Rock, which is 20 miles outside of Texas. When the local school district debated whether to removed Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You from the curriculum–the book is a youth adaptation of Ibram X. Kendi’s Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, which won the 2016 national book award for nonfiction–thousands of parents, teachers and community members signed a petition calling on the district’s board of trustees to keep the book on school shelves:

One way the parents association did this was organizing groups such as ACT (Anti-racists Coming Together)to speak out in support of diverse literature at a local school board meeting.

“Taking away that book would have completely whitewashed history, and that’s not what we are for,” Ashley Walker, 33, one of more than 400 members of the Round Rock Black Parents Association, said.

The district’s trustees eventually decided to keep the book, so chalk one up for progressive counter-pressure. The forces of reaction and intolerance don’t always win out.